These are my speaking notes and discussion notes from today’s School of Literature, Media, and Communication Conversation following Robert Darnton’s talk yesterday on “Books, Libraries, and the Digital Future.” The panelists included Jay David Bolter, Lauren F. Klein (remotely), and me.

We met with an audience of about 25 members of the Georgia Tech community in the Stephen C. Hall Building, Room 102 from 11:00am-12:00pm.

- My research in the area

- My interest in eBooks comes from two tangents.

- First, it comes from my research interests in video game narratives in older software for the Commodore 64, Amiga, IBM-PC, Apple II, and Apple Macintosh platforms. Part of this research focuses on the way characters read within the game—particularly, computer based reading on terminals, tablets, virtual displays, etc. and how these ideas filter into reality/production and vice versa.

- Second, it comes from my dissertation research on something that William Gibson wrote about obsolescence and how our technologies—typewriters, Apple IIc, etc.—are fated to become junk littering the Finn’s office—in an “Afterword” to his Sprawl trilogy of novels: Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive [To read it, scroll to the bottom of this page]. The trouble with sourcing this text was the fact that it was not published in a physical book. Instead, I discovered from a Tweet that a mutual friend made with the writer that it come from an early eBook designed for the Apple Macintosh Portable by Voyager Company (what’s left of this company today creates the Criterion Collection of films).

- Gibson, William. “Afterword.” Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive: Expanded Books. Voyager Company. 1992. TXT File. Web. 25 March 2012.

- Gibson has done other things with ebook and experimental writing such as his exorbitantly priced Agrippa: A Book of the Dead, a floppy disk based e-poem that erases itself after “performing” one time.

- Since working with Gibson’s ebook, I’ve begun studying other ebooks—rediscovering ones that I read a long time ago and rethinking what constitutes an ebook—thinking about encyclopedia precursors to Wikipedia and other software such as the Star Trek: TNG Interactive Technical Manual, which does on the computer things that Rick Sternbach and Michael Okuda could not do in their print Technical Manual.

- We can talk more about this later, but I support Aaron Swartz’s “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto.” In my research, I have deployed my own tactics for reading and manipulating text that enable scholarship that I otherwise would be unable to do. Read more about fair use and transformation.

- My interest in eBooks comes from two tangents.

- My response to Darnton’s talk

- Aaron Swartz’s “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto”

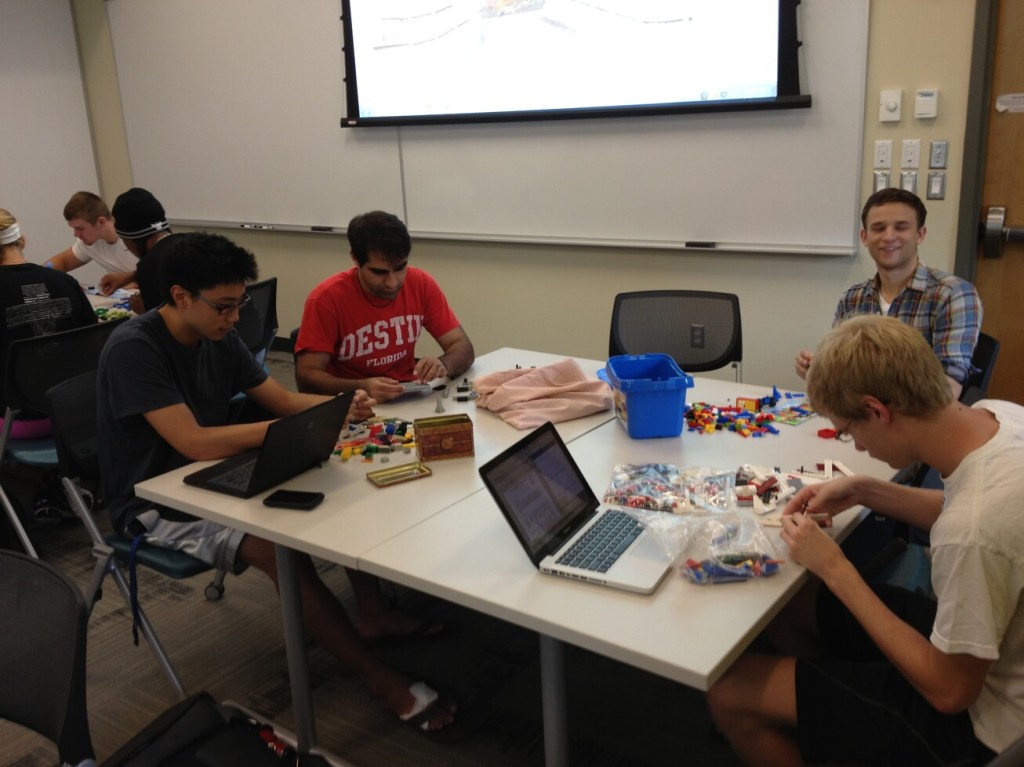

- Peter Purgathofer’s Lego Mindstorms-MacBook Pro-Kindle-Cloud-based OCR assemblage for ripping text from Kindle ebooks

- DPLA scans of Dickinson’s manuscripts (open) and copyrighted scholarly editions (closed).

- Issues of the Archive, Access, and Control.

- My suggestions for future research directions

- The relationship between haptic experience of pulp books and ebooks (e-reader, tablet, computer, Google Glass, etc.). How do we read, think about, and remember books differently based on the modalities of experiencing the book? We know that the brain constructs memories as simulations, so what are we gaining and losing through alterations to the methods of interacting with writing?

- A history of eBook readers—fascinating evolutionary lineage of ebook reading devices including Sony’s DD8 Data Discman (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_Discman).

- How are our students reading? More students this year than last asked me if they could purchase their books for ENGL1101 and Tech Comm as ebooks. How many students are turning to ebooks due to their cost or ease of access (pirating)? I don’t mind students purchasing ebooks over traditional books, but I have them think about the affordances of each.

- As researchers, how should we assert our fair use of texts despite the intentions of copyright holders? We no longer own books, but instead, we license content. [Purgathofer mentions this, but Cory Doctorow and others have commented on this at length: one source. Another more recent source.]

- How do we use ebooks and traditional books differently/similarly? For example, Topiary (aka Jake Davis), one of the former members of LulzSec, said earlier today on ask.fm that he prefers ebooks for learning and studying, but he prefers traditional books for enjoyment.

- Other responses, comments, and questions

- Jay Bolter: What about the future of books, the status of the book, and the status of libraries? What will happen to literature and the literary community? What is the cultural significances of print/digital to different communities (e.g., general community of readers vs. community represented by the New York Review of Books)?

- Lauren Klein: What are the roles of the archive and how do readers access information in the archive? We should think about how people use these digital archives (e.g., DPLA). In her work, she deploys computational linguistics: techniques to study sophisticated connections between documents. How is the information being used? Deploying visualization techniques to enable new ways of seeing, reading, and studying documents.

- Grantley Bailey: What about people who grow up only reading on screens/ebooks? What will their opinions be regarding this debate?

- Aaron Kashtan: Commented about graphic novels and comics in the digital age and about how these media remain entrenched in traditional, print publishing. Also, Aaron is interested in materiality and the reader’s experience.

- John Harkey: Commented on poetry’s dynamism and its not being wedded to books/chap books. Poetry is evolving and thriving through a variety of media including the Web, as electronic art, and experimental literature. We should think about literature as vehicles of genres and artifactual heterogeneity (essay, collage, posters, augmented reality, etc.).

- Lisa Yaszek: Pan-African science fiction is likely a model for the future. In the present, no single nation can support a thriving publishing industry for SF, but together, African SF is taking off with the diffusion of new technologies of distribution and reading (ubiquity of cellular phones, wifi, cellular data, etc.).