ChaosPoetry Generator 1.2 (downloadable from the TextWorx Toolshed) is a Hypercard stack for Macintosh that strings together words, phrases, and sentences from seven lists that its built-in script randomly pulls from to create combinations that might be interesting, nonsensical, disturbing, or offensive.

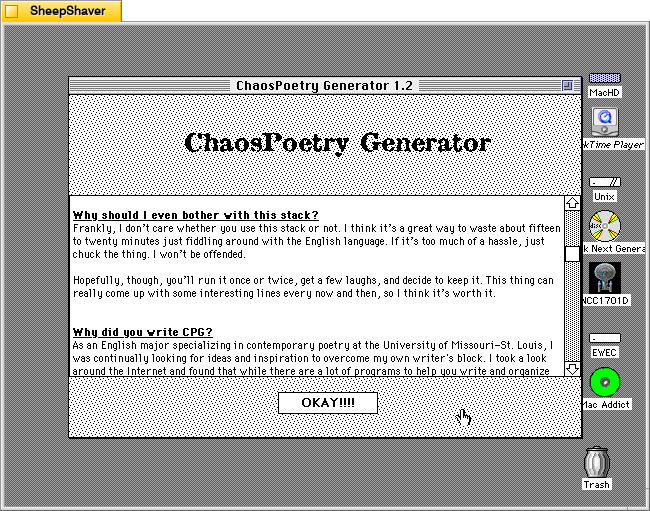

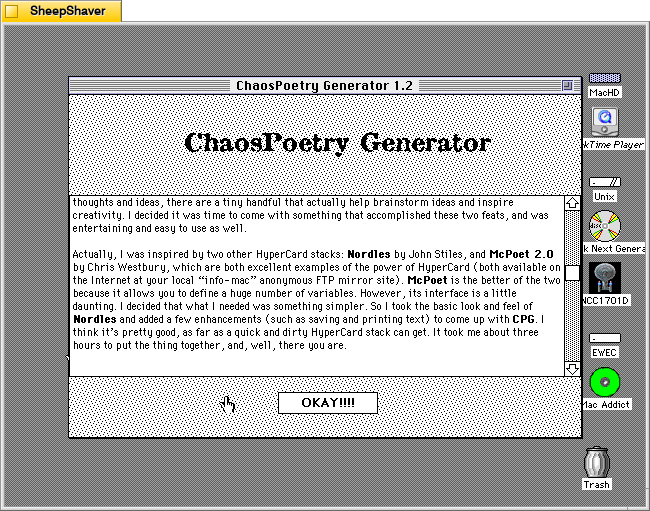

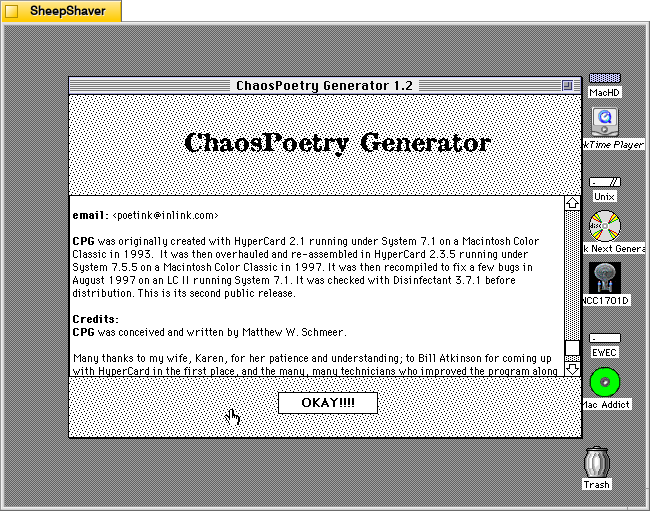

It was made by Professor of English Matthew P. Schmeer when he was an undergraduate studying contemporary poetry at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. He notes that it was inspired by Nordles (I will post about this soon) and McPoet 2.0 (post about version 5.1 is here).

The abstract that accompanied the file in the Info-Mac Archive provides some more details about its use and purpose:

#### BINHEX chaospoetry-generator-12.hqx ****

From: poetink@inlink.com

Subject: ChaosPoetry Generator 1.2.sit

ChaosPoetry Generator is a HyperCard based writing tool to help writers break through writers block. Full documentation is included within the stack, but a simple explanation is that ChaosPoetry Generator is a random string generator wherein you control the strings.

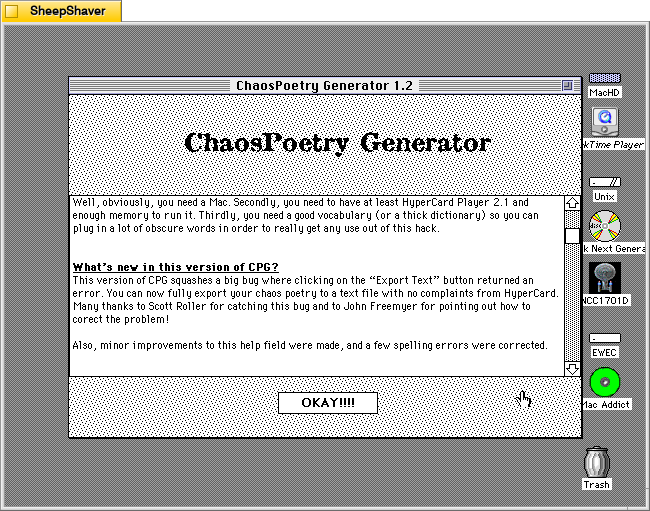

This version corrects a major bug which would not allow you to save your generated text. This has been fixed, and now CPG allows full text export.

We give our permission for this file to be included on the Info-Mac CD-ROM, with our usual stipulations.

Thank you.

Matthew W. Schmeer

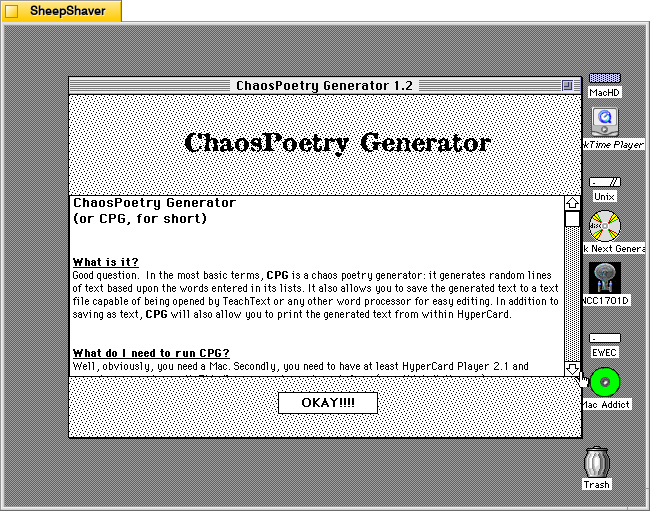

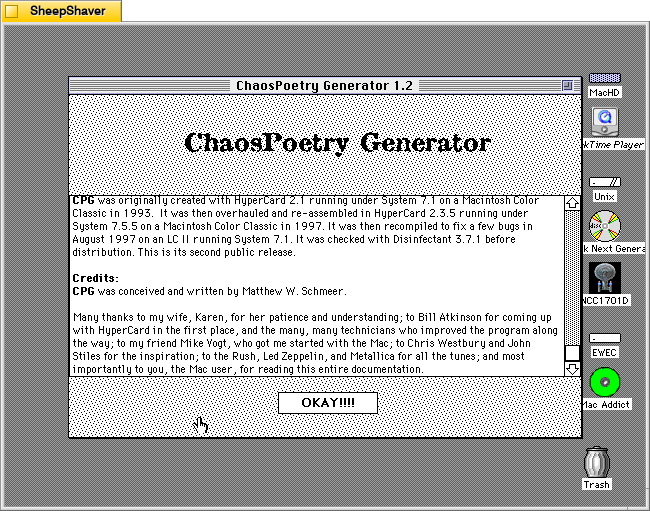

<poetink@inlink.com>Inside the Hypercard stack’s about page (screenshots further below), Schmeer writes, “In the most basic terms, CPG is a chaos poetry generator. It generates random lines of text based upon the words entered in its lists. It also allows you to save the generated text to a text file capable of being opened by TeachText or any other word processor for easy editing. In addition to saving as text, CPG will also allow you to print the generated text from within Hypercard.”

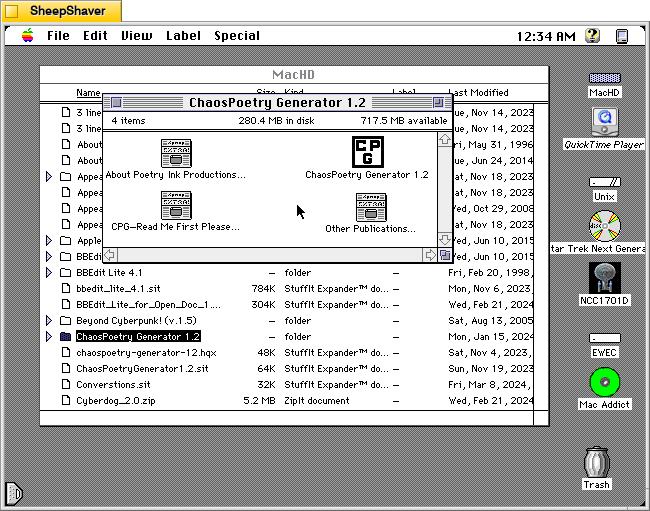

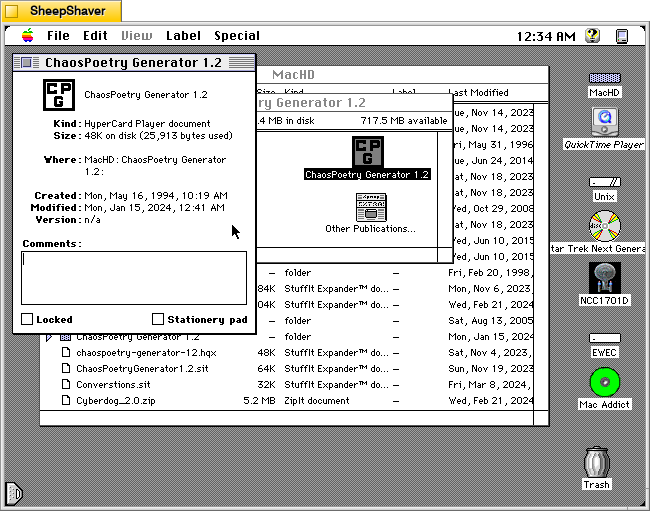

The Get Info window on the Hypercard stack reveals that it is very lean at 48K on disk (25,913 bytes).

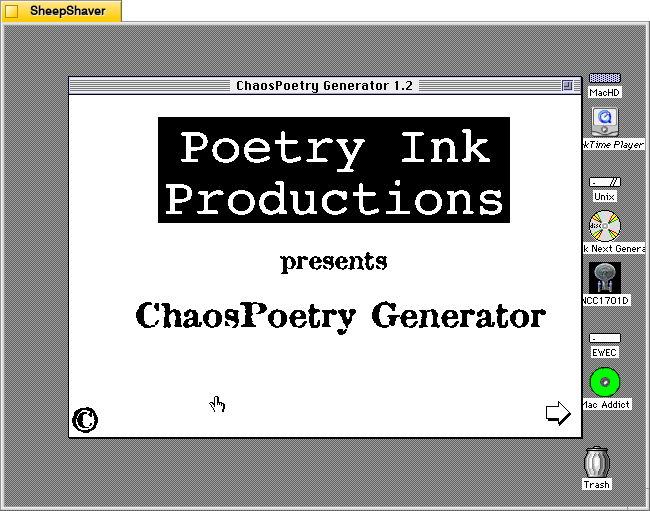

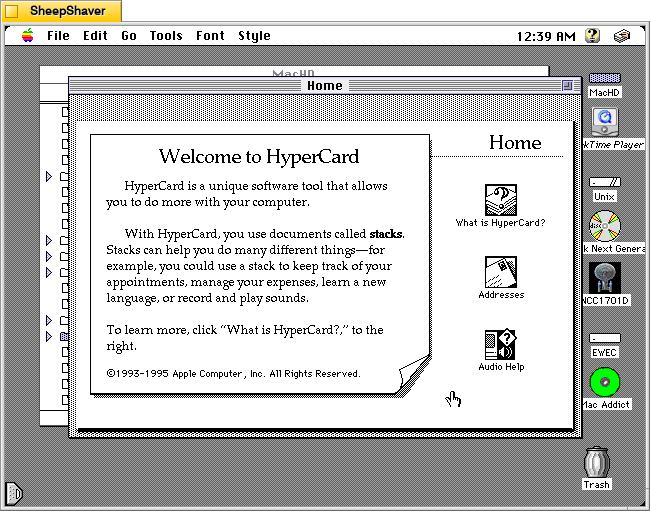

Double clicking on ChaosPoetry Generator 1.2 launches the Hypercard stack in Hypercard Player, which needs to be installed on the host system.

Clicking on the copyright symbol in the lower left corner brings up this “©1997 Poetry Ink Productions” window.

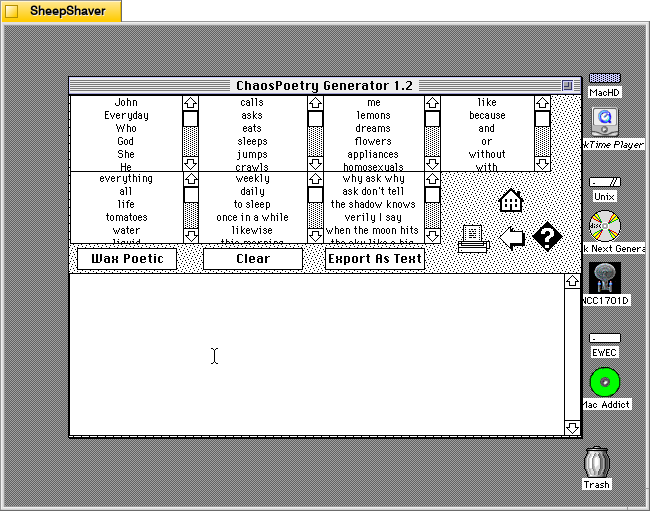

Clicking the arrow in the bottom right of the launch window brings the user to the text generator. Each of the seven lists can be edited by clicking into them, editing a line, or scrolling to the bottom and adding new text to the list there.

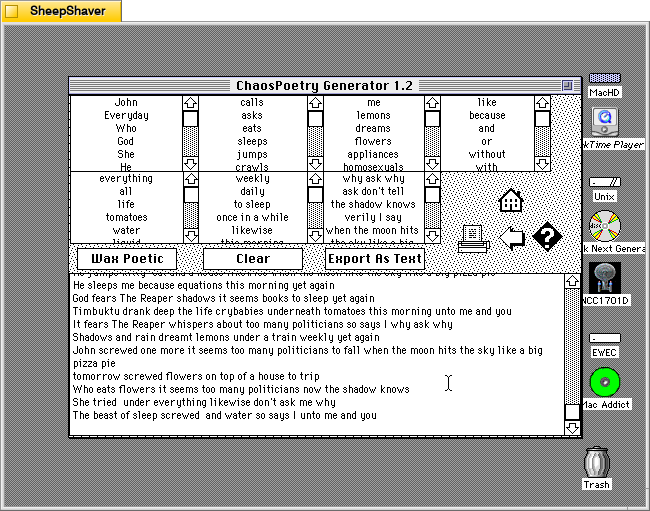

Clicking once on the “Wax Poetic” button causes ChaosPoetry Generator to begin generating copious and unending lines of text randomly drawn from the seven lists at the top of the window. The “Wax Poetic” button changes to “Click to Stop,” which when pressed, ceases the text generation. The user can scroll back up the output box at the bottom of the window to read through the generated lines of text. Clicking on the “Clear” button erases the generated text box, and clicking on “Export as Text” gives the user an option to save the generated text as a TeachText document. The printer icon on the right of the window gives an option to print the output in the generated text box.

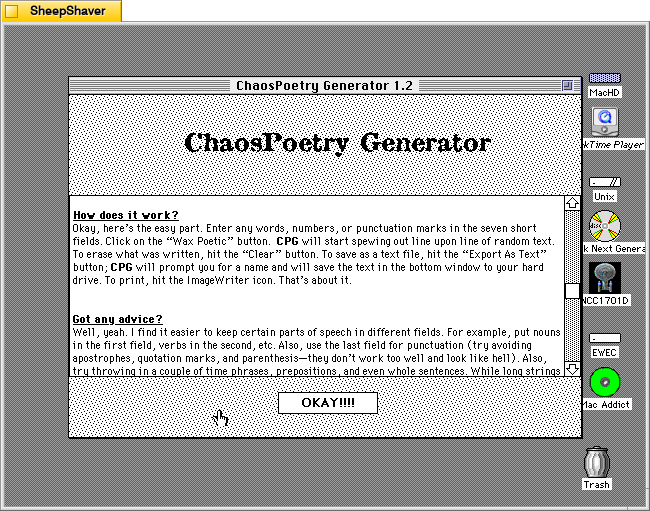

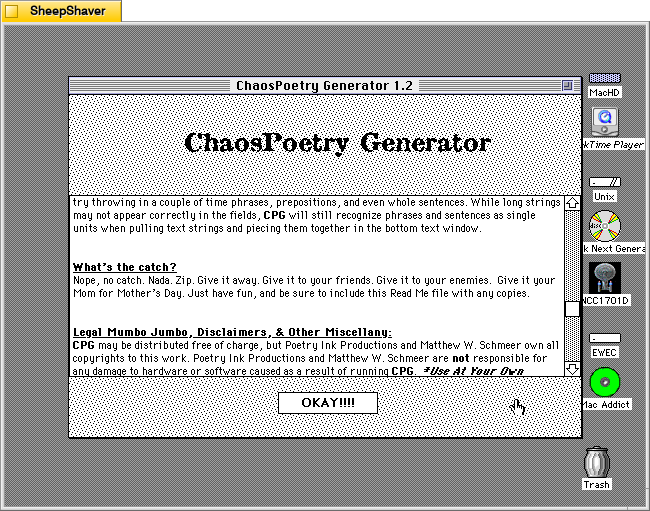

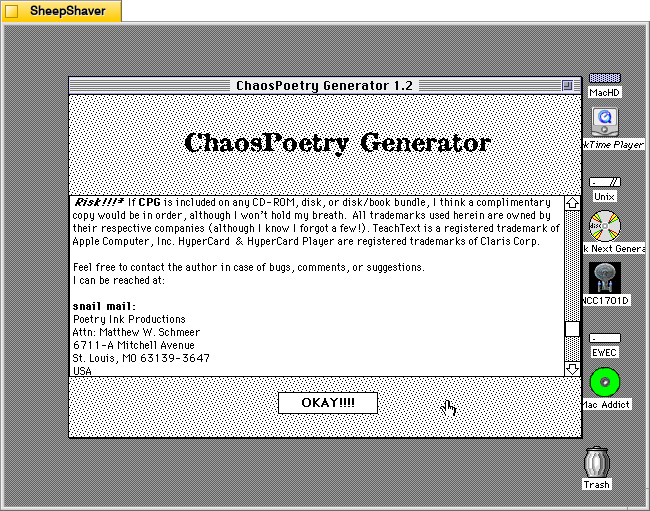

Clicking on the question mark icon on the right side brings up ChaosPoetry Generator’s info page that includes information about what it is, what’s needed to run the stack, what’s new to this version, why it was written and its inspirations, how it works, and advice on using it. Screenshots of these pages are included above, but the key takeaway from the advice section is that the user should use each column for a different parts of speech: a list of nouns, a list of verbs, a list of adjectives, a list of phrases, etc. Schmeer also notes that punctuation marks should be avoided as “they don’t work too well and look like hell.”

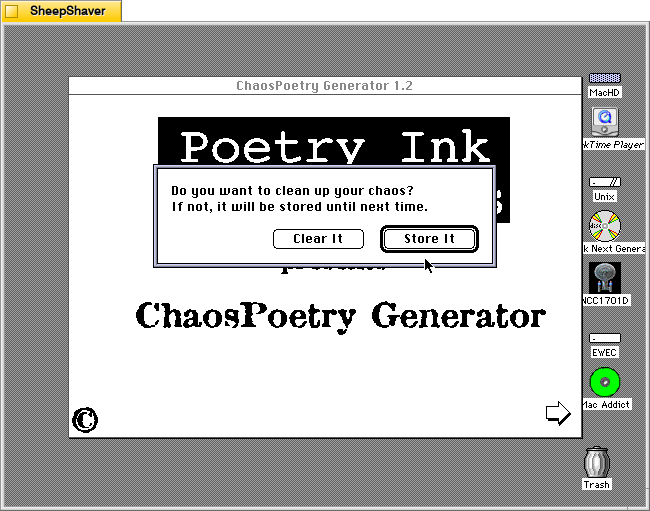

Clicking the Home icon on the text generator window first prompts the user if they would like to clear the generated text or store it.

After making a selection on clearing or storing the generated text, the user is taken back to the Hypercard home screen and have essentially quit ChaosPoetry Generator.

The more that I explore these early examples of text generators, the more I come to realize that the meaning making isn’t so much in the way that they work (with exceptions) but instead in the meaning that we give to their outputs. ChaosPoetry Generator, like some of the other text generating applications and Hypercard stacks for Macintosh of that era, are like a warehouse of monkeys, each typing away frantically on their own typewriter. Given enough time and enough monkeys, eventually they will produce the works of Shakespeare (I first heard about the warehouse of monkeys from Douglas Adams, but the theory is much older). But before we get to that point, there’s going to be a lot of not-Shakespeare output. It’s that stuff that we humans read and think about and give meaning to. The computer, of course, has assembled the words in a certain order, but how those words are understood depends on us interpreting the words and choosing to use them or not, if you’re a writer using ChaosPoetry Generator as a tool, for example.