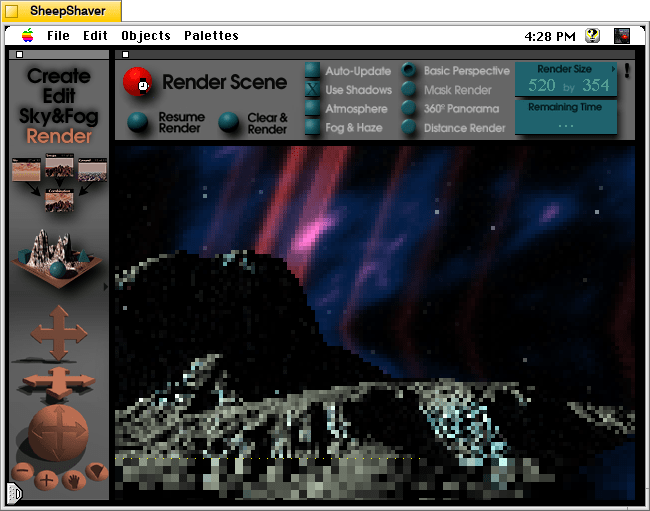

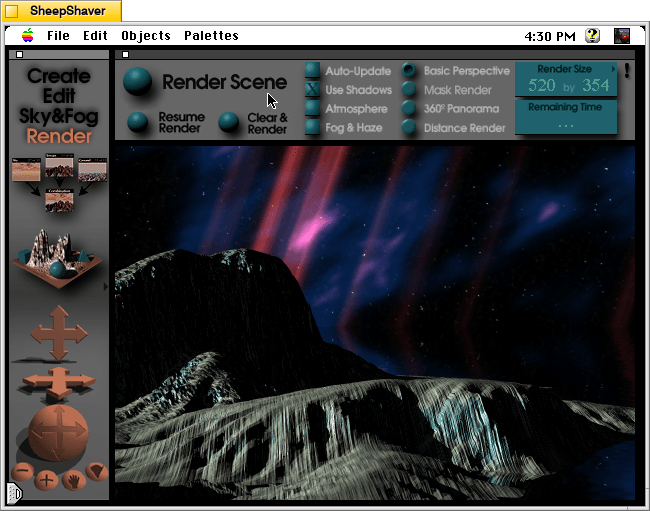

Like I’ve written before about image generation software such as KPT Bryce and Evolvotron, which employ fractals instead of artificial intelligence (AI) to generate landscapes and abstract images respectively, there are also text generating programs that use a variety of coding tricks to string words together in a far less complex manner than those used by large language model (LLM) AI systems today. Nevertheless, these precursors to generative AI deserve our attention to explore how they work and what they might have been and still used for.

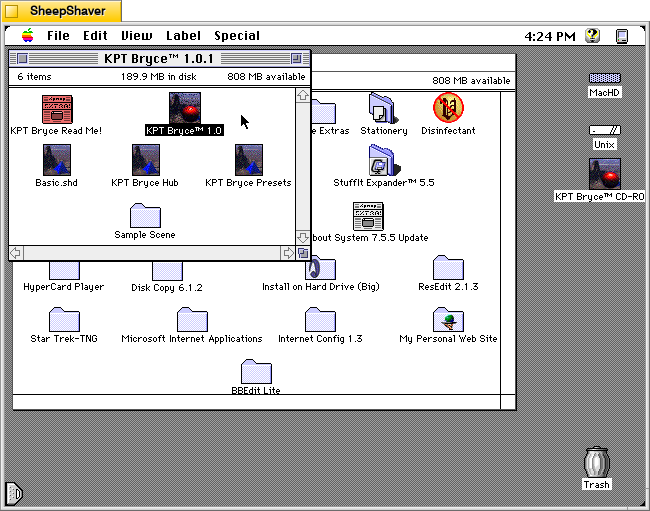

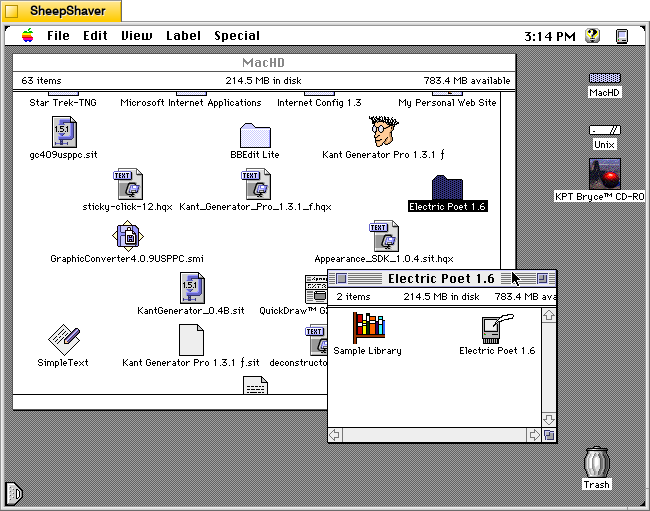

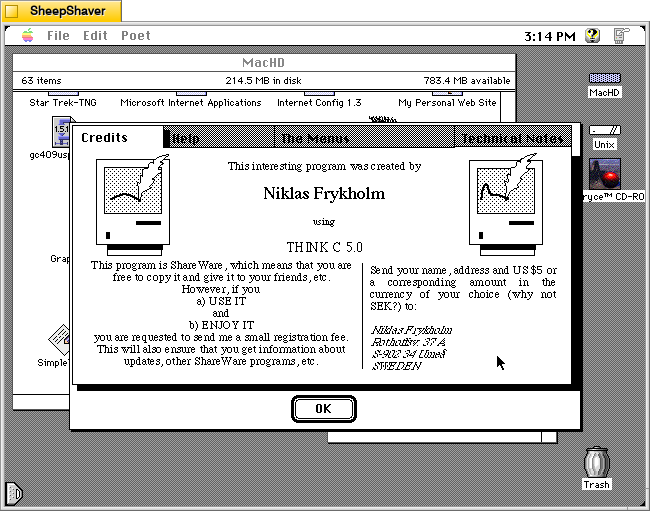

One such text generating program is Electric Poet 1.6 by Niklas Frykholm. It is a program that is only 48K in size, uses 600K of RAM, and is built to run on 68K-based Macintosh computers. For testing and creating the screenshots below, I used SheepShaver running System Software 7.5.5.

In his abstract for the Info-Mac Archive (available in a viewable format here or as a part of the entire Info-Mac archive here), Frykholm writes, “Electric Poet can use an ordinary text file as a mould for creating its own litterary [sic] works. This works best with abstract poetry where it’s sometimes hard to tell real from bogus.”

On 28 Sept. 1996 on his personal website, he writes, “Electric Poet is a fusion between my interest in computers and my interest in poetry. It is an attempt to write a program, capable of creating its own literary works. The Electric Poet takes the works of a biologic poet (as a TEXT-file) and rearranges them in a random but controlled manner. Heres a poem written by the program:

often

and closer to the chasm

until you still have been squeezed by the mysterious event

it showed clearly for the trouble

and the progress

about my desktop”

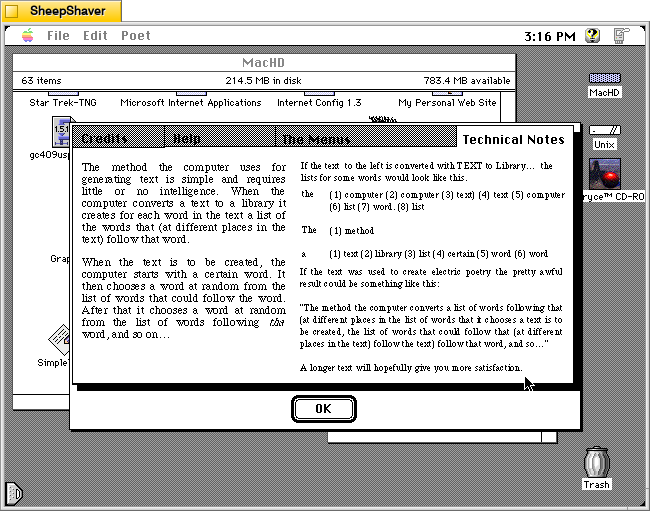

And according to Frykholm’s “Technical Notes” on the program’s About window, “The method the computer uses for generating text is simple and requires little or no intelligence. When the computer converts a text to a library it creates for each word in the text a list of the words that (at different places in the text) follow that word.”

“When the text is to be created, the computer starts with a certain word. It then chooses a word at random from the list of words that could follow the world. After that it chooses a word at random from the list of words following that word, and so on . . .”

Essentially, Electric Poet is a clever piece of software that uses word relationships within a given text to create text based on random selections within that set of relationships.

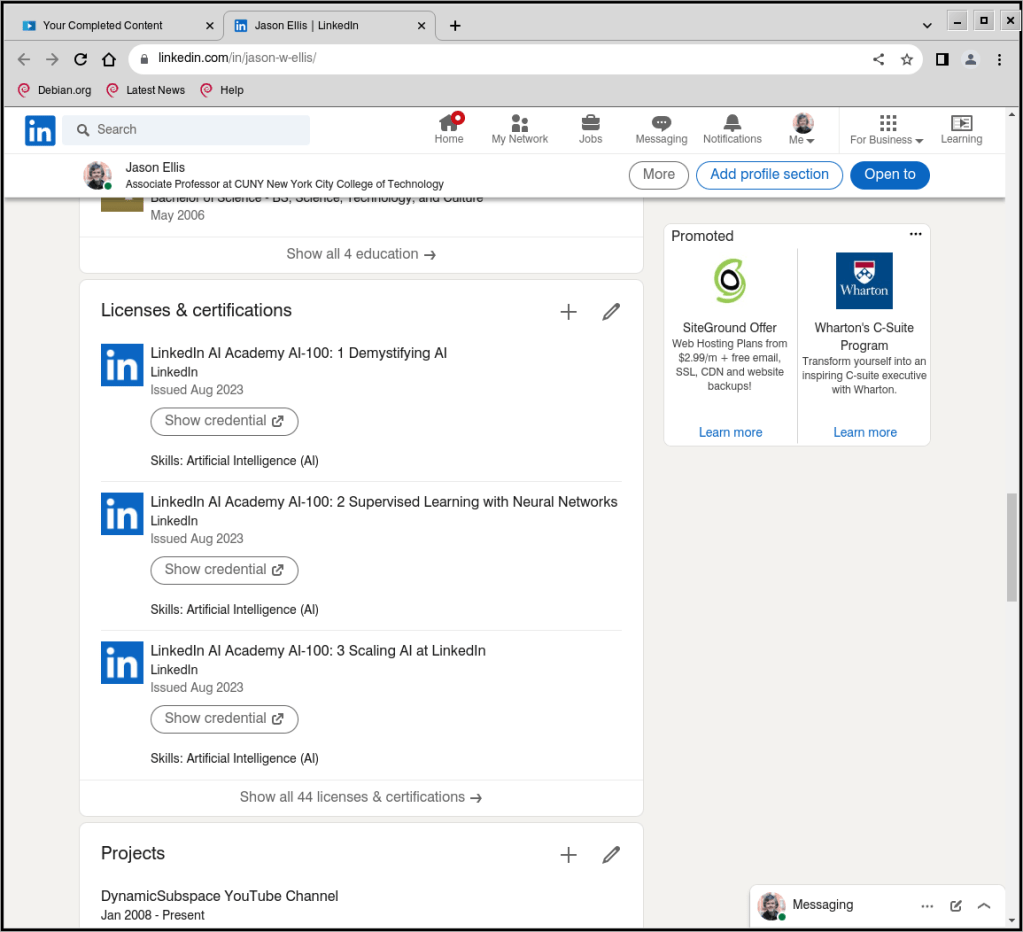

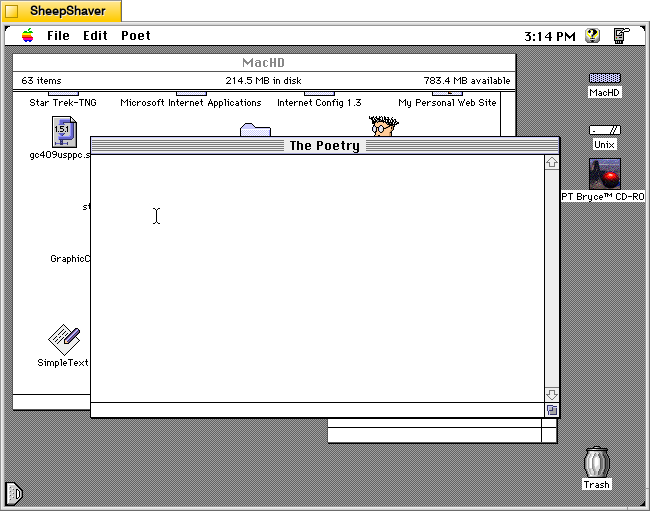

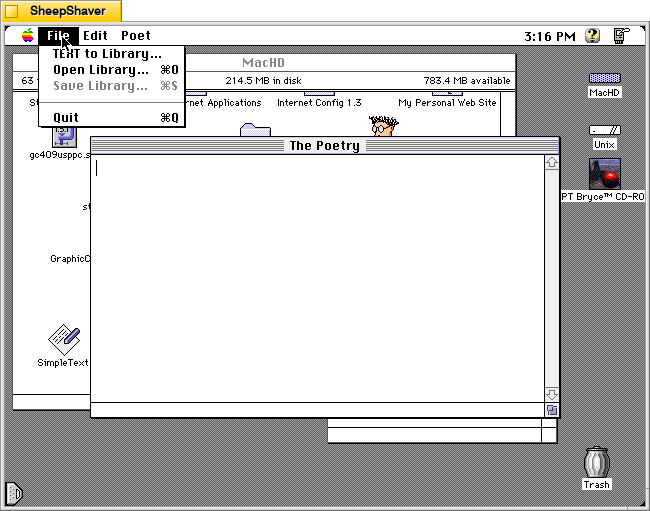

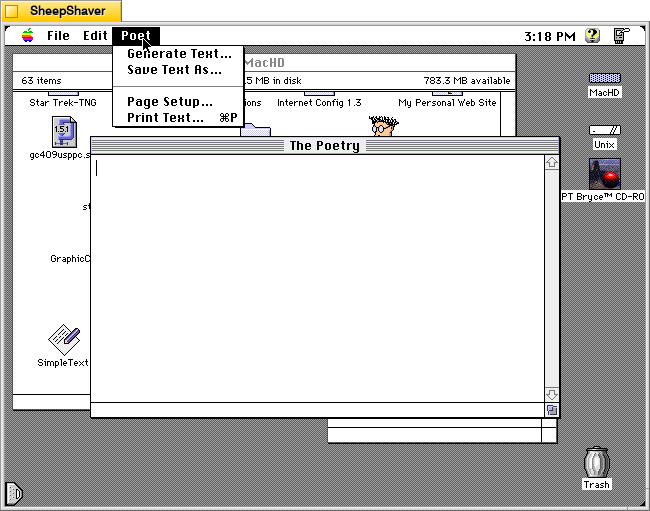

After double clicking on Electric Poet 1.6 in the icon group shown at the top of the page, the program presents “The Poetry” window with a blinking cursor. To have the program generate poetry, the user needs to open a Library from the File menu and then choose “Generate Text” from the Poet menu.

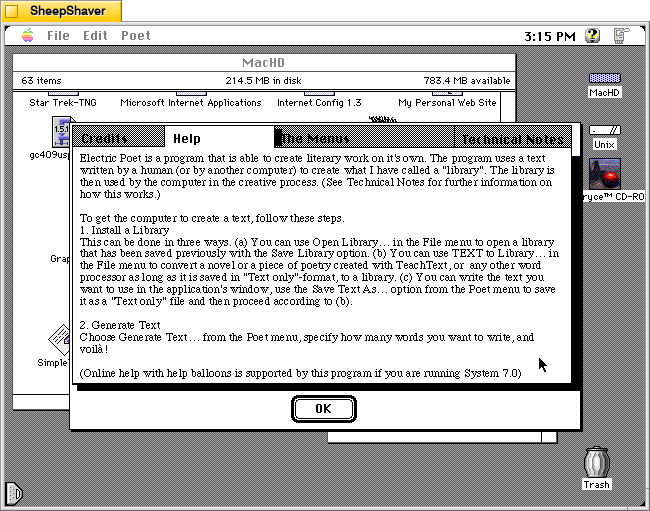

Opening the “About Electric Poet” from the Apple menu gives the user a super helpful set of tabs that gives you information for registering the shareware program, help using the software, an explanation of the menu items, and technical notes about how the program works to generate text.

The About Electric Poet’s Help tab breaks down what the user needs to do so that the program generates text. The first step is to “install” or open a Library. While Electric Poet comes with a sample Library based on the script for the film Star Wars, most users would probably want to create their own Library, which is easy enough to do. Once the Library is created and loaded, Electric Poet can then generate text from the Poet menu.

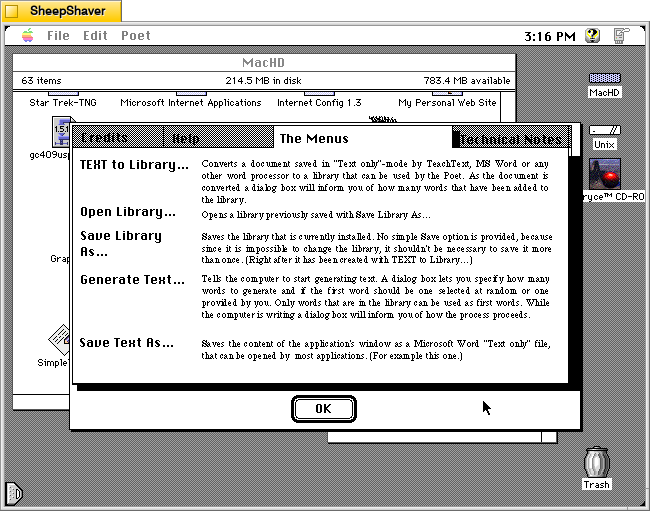

The About Electric Poet’s The Menu tab gives further explanation about what each menu option does in the program.

The About Electric Poet’s Technical Notes provides details about how it uses lists of words and the words that follow immediately after those words as a corpus of random selections linked to adjacent words. This is the magic that makes this program generate text. It uses lists of adjacent words and random selection to thread together sentences and phrases.

To get started with Electric Poet, the File menu gives you access to opening a Library or creating a Library from “TEXT to Library.” It’s important to note that you need to have your text file in Teach Text format before attempting to create your own Library. I discovered that when opening a raw text file the program would create a list of words (as it would normally when creating a Library), but then the program would lock up and while I could still move the mouse, I could no longer use the menu, switch programs, or activate the Finder. I would have to kill the SheepShaver process on Debian and relaunch. I observed this same behavior when running Electric Poet on the 68k emulator Basilisk II.

To avoid this problem, open your raw text file in BBEdit or another full-featured text editor (if it is larger than 32K–the Teach Text limit), copy an excerpt to the Clipboard, and then go into Teach Text, paste the text, and save it as a file. Then, use “TEXT to Library” in Electric Poet to create a Library from that Teach Text-saved file.

Once you’ve opened your Library file, you can now use the Poet menu to “Generate Text.”

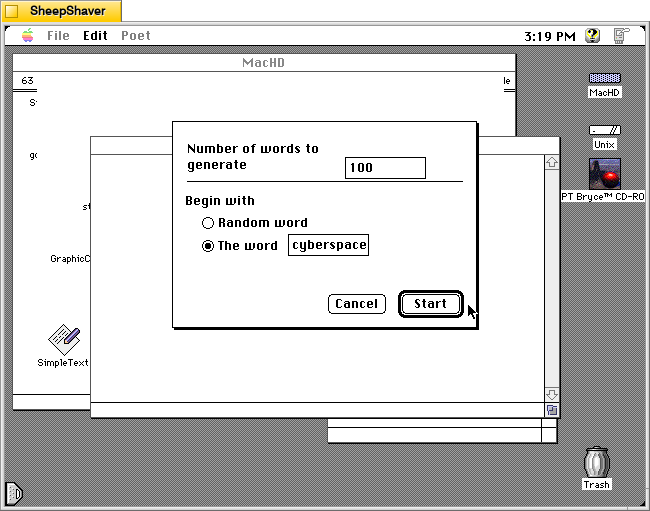

The “Generate Text” menu option presents you with these controls before generating some text in “The Poetry” window. It allows you to choose how many words to generate and the option to begin with a random word or a specific word. If you choose a specific word, bear in mind that it is case sensitive. For example, I tried beginning with “Cyberspace,” but the word was not found in the Library. I tried with “cyberspace” and it generated text as shown below.

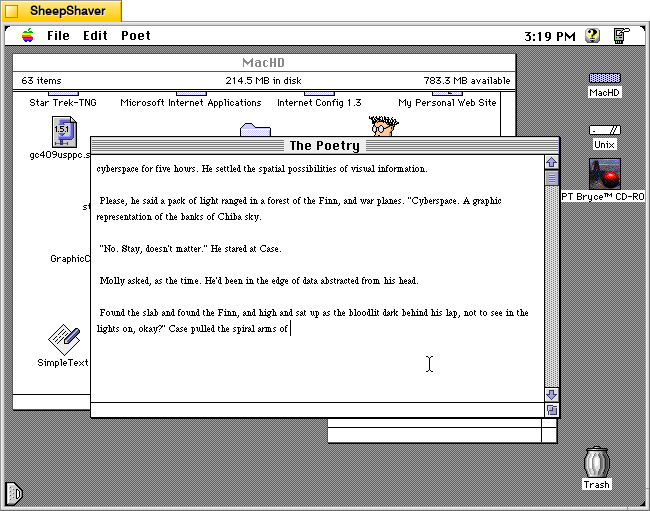

Above, is a sample of text generated from “The Shopping Expedition,” the third chapter of William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984). This example is just one run. Subsequent runs will yield very different results. In this regard, it is like using Stable Diffusion or LLaMA in that many iterations are often required to generate an output that is desired by the end user.

Soon, I’ll post about Kant Generator Pro, another Macintosh text generator program that creates pseudo-sense/technobabble text (writing like the philosopher Kant) as well as form generated writing, such as thank you notes. The form generated writing that Kant Generator Pro can do is aligned with one of the kinds of writing large language models are supposed to be able to help us with–emails, follow-ups, etc.