Continuing the work that I started in 2014 when I wrote about the rediscovery of a set of isometric Macintosh icons that I had created and shared in 1997, I wanted to share another rediscovery from February and March 1997 that spans a defunct Macintosh-focused blog called the Power Macintosh Resource Page and Usenet that involves BeOS, winning a magazine, and writing about a hard drive partioning trick that I developed using free BeOS and MacOS applications.

This rediscovery came about after I sent a postcard to another computer enthusiast via Postcrossing.com. I wrote in my postcard about how great I thought BeOS was. She replied that she hadn’t used BeOS before but was interested in it.

I remembered that the way that I came to use BeOS for a time was thanks to a now-defunct technology blog called The Power Macintosh Resource Page. It was operated by Steve Tannehill.

On 1 Feb. 1997, Tannehill posted this message to his site (which you can find in the site’s archives saved on the Internet Wayback Machine here):

1 February 1997:

Trevor Inkpen wrote to mention that the Complete Conflict Compendium is about to have its 500,000th visitor. That visitor will win an Apple watch and an Apple hat.

Not to be outdone… ;-)

In the next 2-3 weeks, the Power Macintosh Resource Page will hit the half-million mark. If you send me a legitimate screen shot of the 500,000th hit, I’ll send you a copy of the January MacTech magazine, complete with the BeOS for the Power Mac demo CD-ROM!

Power Macintosh Resource Page, Feb. 1997 Archive, Archive.org Wayback Machine.

There are a few things to unpack here. First, Tannehill mentions Trevor Inkpen’s site visitor context for “an Apple watch and an Apple hat.” That Apple watch prize was not for what we think of as an Apple Watch today. It was an Apple-branded watch that Apple sold through their campus gift shop in Cupertino.

Second, website operators used to pride themselves on how many site visitors they had. This was usually calculated with a public-facing counter enabled by a bit of code offered by a provider that logged page loads containing the code and presented a gif-based numerical counter of the number of page loads. Many of these counters only provided a simple calculation of page loads rather than the more granular information provided by webserver logs and the more advanced metrics of unique visitors, engagement, etc. used today.

Third, like Inkpen’s website with a counter nearing 500,000, Tannehill’s Power Macintosh Resource Page’s counter was also nearing that number. So, he devised a contest to reward the person who was the 500,000th visitor. Unlike Inkpen, Tannehill offered what I considered a greater prize, a copy of the January 1997 issue of MacTech Magazine, which included a CD-ROM installer for the Preview Edition of BeOS.

Before Tannehill offered this prize, I had heard about BeOS from articles in Mac magazines like MacUser, Macworld, and MacAddict. With the burgeoning world of online reporting and news, I had gleaned even more information about it. It sounded like the next big thing, especially in light of Apple’s financial troubles of that era.

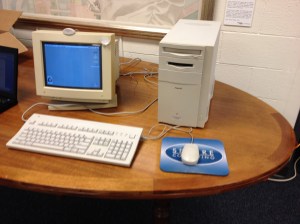

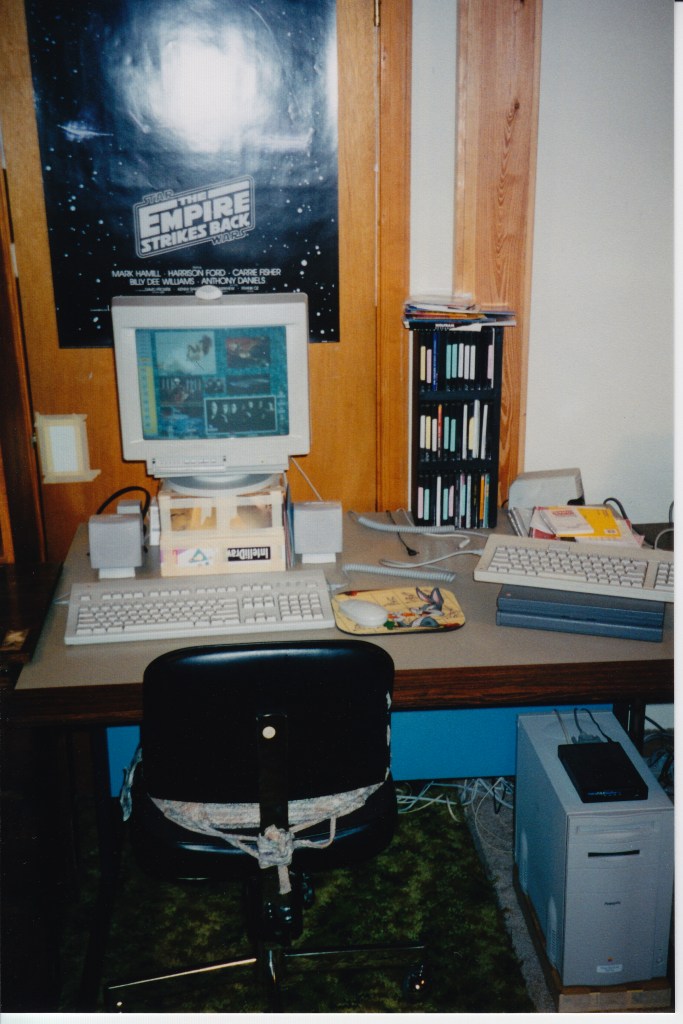

Also, I had gotten my PowerMacintosh 8500/120 only a year before, so I had a computer that was capable of running the PowerPC-based BeOS Preview Edition that came with the MacTech Magazine.

After learning about Tannehill’s contest, I first thought that there is no way that I would be lucky enough to be the 500,000th visitor to his site. So, the practical solution was to find a copy of the magazine. I was attending Georgia Tech in Atlanta at the time, so I had access to bookstores with nice magazine selections–the best being Tower Records next Lenox Square Mall in Buckhead.

Unfortunately, I was unable to find a copy of the magazine anywhere. Stores that sold MacTech said that they were sold out. Therefore, my only alternative to obtain a copy of BeOS was to be a super visitor to the Power Macintosh Resource Page. Thankfully, my efforts paid off on 13 Feb. 1997 after I revisited the page late that night and took the required screenshot of my browser window:

13 February 1997:

Jason Woodrow Ellis is the official 500,000th visitor to the Power Macintosh Resource Page! Jason sent the screen shot, so he gets the January MacTech magazine. Congratulations Jason, and thanks to everyone for making this page a success!

Power Macintosh Resource Page, Feb. 1997 Archive, Archive.org Wayback Machine.

Tannehill mailed the magazine to my campus address at Georgia Tech, and after receiving it, I promptly began partitioning my PowerMac’s 2GB SCSI hard drive so that I could boot into Mac OS or BeOS (more on this further below).

And, I would be remiss not to remark on how grateful that I am to Tannehill for offering that magazine as a prize on his website. It was a touchstone in my memories of that era of my life and an important moment in my learning more about computers in general and Macs in particular. I owe him a debt of thanks!

While reading the February 1997 archive page of the Power Macintosh Resource Page, I discovered that I had sent in a report about a presentation by an Apple Representative at the Georgia Tech campus:

25 February 1997:

Jason Woodrow Ellis wrote an interesting note regarding a recent presentation at Georgia Tech on the future of Mac OS:

“Apple Computer, Inc.’s Higher Education Account Executive Steve VanBrackle” gave us a very good outlook for the upcoming Rhapsody and MacOS releases. Mr. VanBrackle told us about the NeXT engineers and how “cocky” they were. He explained that these guys say that they could get the NeXT OS to run on a cellular phone! The point was that they are able to port their OS to anything. …if Mr. VanBrackle is correct the engineers will have an easy time of creating it. First, NeXT had ported their OS to PowerPC several years ago to run on 601’s. Second, the Apple AU/X team had already figured out how to run System 7 apps on top of UNIX. Third, 80% of Copland’s old code will be used with Rhapsody, so Apple did not “totally” scrap those several years of research. Now their task lies in combining these things together which in effect is the “easy” part. …I asked him about Jobs and Wozniak’s role at Apple in respect to all of the rumors about Jobs “taking over.” According to Mr. VanBrackle, they are “10 hour per week advisors to Amelio.” They have no managerial responsibilities and no “code time.”

Power Macintosh Resource Page, Feb. 1997 Archive, Archive.org Wayback Machine.

I vaguely remember this presentation only because I recall receiving a copy of the first Mac Advocate CD-ROM, which contained useful software updates, Apple information, and Apple-related media, and Apple rainbow logo stickers, which I later applied to the rear window of my dad’s Toyota pickup truck that I often drove when I was back home (and earned me vulgar responses from homophobic locals who were not only bigoted but also apparently lived under a rock during the first 20 years of Apple Computer’s existence).

It was exciting to me to find this email excerpt that I had taken the time to write and send to Tannehill. I have no memory of what I reported Steve VanBrackle talking about during his presentation, but the points about what would eventually become MacOS X are very intriguing. Behind these points there were a number of important developments. Apple scrapped Copland, the code-named operating system originally intended to become System 8, Apple’s consideration of purchasing Jean-Louis Gassée’s BeOS as the basis of its next-generation operating system, and Apple’s ultimate decision to purchase NeXT and bring Steve Jobs back to the company.

As a side note, I often signed my online posts using my full name at that time, because I had discovered that there are a lot of Jason Ellis’s in the world. Even in my youth, I had to fight accusations of not having had all of my vaccines or needing additional dental work–things that applied to another guy who shared my first and last names and happened to be a patient at my doctor and dentist. When I got online, I found even more people with my name, and I tried to create an identity distinct from others. Eventually, I settled on Jason W. Ellis.

Returning to an earlier point about multi-booting MacOS and BeOS, I found an old Usenet post (thanks to the remnants of Google Groups, which is unfortunately a poor instance of its former glory) that I had made on 13 Mar. 1997–a month to the day after I had won the MacTech Magazine with the BeOS Developer Preview CD-ROM. I cross-posted this short write-up called “Slick Disk Tricks” to comp.sys.mac.hardware.storage and comp.sys.mac.systems (I just didn’t know any better).

Slick Disk Tricks

Mar 13, 1997, 3:00:00 AM

I was a crazy risk taker. I loaded up the BeOS for Power Macintosh on my 8500/120 with only one hard disk drive. Luckily I already had partitioned it when I first bought the computer. I created three partitions: HD1=340MB, HD2= 830, HD3= 830, and an allotment of 33MB of free space.

When I installed the BeOS, I repartitioned HD1 as a BeOS˛ partition. Because I quickly found that I did not find enlightenment from using Be, I wanted to get rid of it. I just as quickly noticed that Apple’s DriveSetup application would not let me repartition without reformatting. This was not an option. Luckily Be came through.

In order to reclaim my first partition I used Be’s included Mac application called BeOS Partition Utility˛ to rename the BeOS˛ partition to an Apple_HFS partition. Then I restarted my computer and a dialogue comes up at the desktop for me to choose to initialize the new partition or eject it. I opted to initialize it (which took all of five seconds) and suddenly I have my first partition back! No special programs or extra drivers necessary. Just as a precaution, I did use Norton’s Wipe Info application to do a nice government˛ sweep of all previously stored data. (OK, so I cheated a little bit!)

I am about to loose my internet connection at Georgia Tech, so I have been trying to download everything under the sun to play with when I go back home this month. This need of space reminded me of my 33MB of free space. This takes a little bit more time and effort than regaining a BeOS˛ partition (but it is exactly the same procedure, almost). These are the steps that I used. First, I used the BeOS Partition Utility˛ to rename the Apple_Free to BeOS. Next I launched the BeOS from the CD-ROM and initialized this the free˛ partition for use by the BeOS (this gives the partition a name). Next I rebooted my computer after _not_ installing the BeOS and again used BeOS Partition Utility˛ to rename the BeOS˛ partition to Apple_HFS.˛ Now one can see that this is similar to the previous instructions. However when I restarted nothing happened! Well, undaunted, I used Apple’s DriveSetup app to update the disk driver. I rebooted and now my free space is a new partition asking to be initialized. I now have my full hard disk drive available for storage purposes.

One should realize that what I did was very perilous and down right horrific. I don’t have any kind of backup solution or another disk drive to keep files on. Please use caution if you try this technique to reclaim disk space! And, remember, I am loosing my email address shortly so you have no ability for flames or other such nonsense.

Jason Woodrow Ellis

Google Groups, comp.sys.mac.system, 13 Mar. 1997.

gt0…@prism.gatech.edu

While I wrote this with the intent of sharing a neat way to use the BeOS Partition Utility and Apple’s DriveSetup programs to resize and reclaim hard drive space without the need of paid partitioning software, it is an embarrassing piece of writing. However, I try to remind myself that it was something that I wrote about 25 years ago, which puts it in its proper context.

Also, I’m saddened to read that I wrote, “I quickly found that I did not find enlightenment from using Be.” I don’t recall exactly why I didn’t find it enlightening. From my viewpoint now, BeOS was exciting to use and had an excellent user interface (UI). But, I can imagine how it might not have been a daily driver OS due to its development stage and a fewer application options than MacOS. Also, hard drive space cost a premium, so I probably wanted to have the drive space back for other projects that I was working on at the time. So, while my 1997-self might have not found enlightenment from BeOS, my present self recognizes BeOS as something that had the potential to be insanely great (Steve Jobs would probably not appreciate my borrowing his phrase for this case, but I think it applies nevertheless). And I do know that despite my not keeping BeOS installed on my PowerMacintosh, I enjoyed using Greg Landwebber’s BeView to reskin MacOS as BeOS (and, I alternated between BeView and Aaron, for a Copland look–later, I switched to Kaleidoscope). And, I am certain that BeOS left an indelible imprint on my mind for me to think of it to this day, including its incredible design choices–isometric interface icons, tabbed windows, the application dock, and the finger pointer, as well as its amazing under-the-hood developments with its microkernel, preemptive multitasking, multithreading, etc.

I am curious about the phrase that I used: “did not find enlightenment.” It makes me wonder if an advertisement or article about BeOS used that kind of language to describe using it. When I have some time, I’ll look into that with what’s available on archive.org, Google Books, and other places online that might have digital copies of mid-to-late 1990s Macintosh magazines.

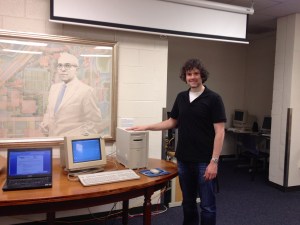

After upgrading its cache memory and its CPU daughter card to a faster 604e processor, I sold my PowerMacintosh to an ex-girlfriend. Later, I acquired another PowerMacintosh 8500/120, which I donated to the Georgia Tech Library’s Retrocomputing Lab before moving to NYC.

A few final notes: Haiku OS is trying to build something new that captures what BeOS once was and could have been. I haven’t had a chance to try it out yet, but I certainly intend to! And, I owe a great deal of thanks to the Internet Archive for the Internet Wayback Machine and Google Groups (despite Google’s mishandling of this invaluable resource), both of which made this personal exploration possible. While many of our digital traces seem to linger, others disappear without the dedicated and important work of digital preservationists.