I collected the following notes, resources, and readings to share during today’s Empowering Faculty with AI roundtable discussion organized by City Tech’s Academic Technologies and Online Learning (AtoL).

These resources are divided into these sections: Writing and Editing, Research and Experimentation, Teaching, and Readings for Faculty.

I tend not to trust a computer that I can’t throw out the window, so I only use local Generative AI models that I can run on my desktop workstation or Lenovo ThinkPad P1 Gen 4 laptop. My primary interests are in text generation and image generation, which I have documented over the past three years here on DynamicSubspace.net.

Writing and Editing

- I used Generative AI to edit my writing and create the cover image for Yet Another Science Fiction Textbook (YASFT) OER that I published on my website in Feb. 2024. I included an explanation of my workflow in the front matter of the textbook.

Research and Experimentation

- I write about pre-LLM forms of Generative AI that rely on random number generators, algorithmic grammar, and Markov chains. This page has a list of software that I’ve discussed on my blog.

- I created a workflow using Generative AI to write a cyberpunk science fiction short story titled “Chrome and Punishment” based on Wikipedia’s plot descriptions of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. I used Stable Diffusion to create its cover image. Also, I asked a LLM to perform literary analysis on the finished story.

- I tasked a LLM to rewrite Sydney Lanier’s “Marshes of Glynn” through the lens of Global Warming. I also created a rising seas image of Lanier’s Oak in Brunswick, Georgia using Stable Diffusion.

- I presented on the history of Generative AI in science fiction literature at last year’s Annual City Tech Science Fiction Symposium. These historical examples are generally referred to as “wordmills.”

Teaching

Assigned Readings in Professional and Technical Writing Classes

Introduction to Language and Technology, ENG1710

- Milmo, Dan , Seán Clarke and Garry Blight. “How AI Chatbots Like ChatGPT or Bard Work – Visual Explainer.” The Guardian, 1 Nov. 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/ng-interactive/2023/nov/01/how-ai-chatbots-like-chatgpt-or-bard-work-visual-explainer.

- Blackwell, Alan F. Moral Codes: Designing Alternatives to AI. MIT Press, 2024. MIT Press Direct, https://direct.mit.edu/books/oa-monograph/5814/Moral-CodesDesigning-Alternatives-to-AI. [Chapter 1: “Are You Paying Attention?”]

- O’Neil, Lorena. “These Women Warned Of AI’s Dangers And Risks Long Before ChatGPT.” Rolling Stone, 12 Aug. 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20230813014336/https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/women-warnings-ai-danger-risk-before-chatgpt-1234804367/.

- Christoforaki, Maria, and Oya Beyan. “AI Ethics—A Bird’s Eye View.” Applied Sciences (2076-3417), vol. 12, no. 9, May 2022, https://www.mdpi.com/1595334.

Introduction to Professional and Technical Writing, ENG2700

- Reeves, Carol and J. J. Sylvia IV. “Generative AI in Technical Communication: A Review of Research from 2023 to 2024.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 54, no. 4, 2024, pp. 439-462, https://doi.org/10.1177/00472816241260043.

My AI Use Policy

There’s no doubt (at least in my mind) that the current state of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Generative AI is nothing short of incredible. There are certain tasks AI is good at, there are other tasks AI is not good at, and in all tasks, there is a greater than zero chance that the AI fails at its task horribly and potentially catastrophically. There are legal and ethical considerations, especially for those beginning careers as professional writers and communicators. So, where does AI fit into education, and more specifically, our class? The goals of education include giving students unique experiences for learning, research, and collaboration, as well as opportunities to demonstrate learning, insight, and growth through exams, papers, and projects. Undertaking higher education, changes your brain in deep and important ways that enable you to begin a professional career as a knowledgeable problem solver who is also capable of continuing as a life-long learner. AI’s entrance introduces a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it can be used as a tool to support your work and learning, but it can also be used egregiously to plagiarize and violate the CUNY Academic Integrity Policy. To avoid any misconceptions or misunderstandings, and to support your best learning experience in our class, you may not use AI at all in our class–including email, summarizing, ideation, discussion, or writing–unless the exercise or assignment explicitly states that you may. I am instituting this policy, because I want you to face the challenge of the class using your human abilities, skills, and talents. It’s only through those challenges will you grow and develop into a professional who can do more and find greater success than those who recklessly rely on AI technologies to do their thinking and work. Of course, violations of this policy are simply violations of the Academic Integrity Policy (under definitions 1.1 Cheating, 1.2 Plagiarism, and 1.3 Obtaining Unfair Advantage), which may result in failure and referral to the college.

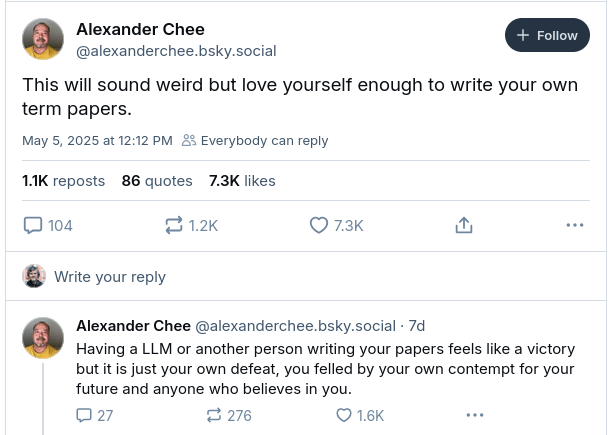

Alexander Chee’s Plea on Bluesky

Alexander Chee, writer and Dartmouth College professor, shares on Bluesky: “This will sound weird but love yourself enough to write your own term papers. Having a LLM or another person writing your papers feels like a victor but it is just your own defeat, you felled by your own contempt for your future and anyone who believes in you.”

Readings for Faculty

I’ve recently been experimenting with so-called reasoning LLM models. For the synopses below, I gave my reading notes to a 6.0bpw quant of DeepSeek’s R1 Distill of LLaMA 70b LLM asking it to turn my telegraphic points into a brief paragraph of prose. Giving the model the “<thinking>” tag before the model’s response engaging the reasoning capability, which tends to provide better results and instruction following. The information that went into the summaries are based on my notes, so any errors or misunderstandings are mine.

- Werse, Nicholas R. “What Will Be Lost? Critical Reflections on ChatGPT, Artificial Intelligence, and the Value of Writing Instruction.” Double Helix, vol. 11, 2023, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/double-helix/v11/werse.pdf.

- Werse examines the implications of ChatGPT—a highly advanced text-generating AI developed by OpenAI—on the future of writing instruction in higher education. He argues that while ChatGPT can mimic human writing and even assist in research and writing processes, over-reliance on this technology risks undermining the critical thinking and deep understanding that writing fosters. He highlights that writing is not just a practical skill but a cognitive process that externalizes thought (citing Kellogg’s The Psychology of Writing–see below), allowing writers to explore connections, organize ideas, and reflect deeply on a topic. Werse acknowledges the benefits of AI as a tool but warns that outsourcing writing to AI may shortchange students of the educational value of engaging in the iterative writing process. He also discusses the broader societal implications, such as how AI could reshape the role of writing in professional contexts, potentially shifting its value from career preparation to personal enrichment. Werse calls for educators to rethink how they teach writing in an AI-driven world, balancing the practical benefits of technology with the enduring importance of writing as a means of learning and critical engagement.

- Kellogg, Ronald T. The Psychology of Writing. Oxford UP, 1994.

- I’ve only just started this book (it’s available to borrow on archive.org here), but I’ve received Kellogg’s thesis about how writing is a cognition supporting technology and activity through many other readings and lessons (though, not always citing Kellogg–it’s more like an established axiom now). Nevertheless, I believe returning to this text is important for building an argument to our students about the importance of doing their own writing for their own thinking and cognitive development.

- Jamieson, Sandra. “The AI ‘Crisis’ and a (Re)turn to Pedagogy.” Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 3, 2022, pp. 153-157.

- Jamieson critiques the panic surrounding AI’s impact on academia, particularly its perceived threat to the college essay and higher education. She argues that while AI tools like ChatGPT, QuillBot, and ParagraphAI are powerful technologies capable of generating sophisticated text, they are not a crisis but an opportunity to refocus on teaching writing. She highlights that composition studies has historically responded to externally defined crises, such as concerns over literacy, cheating, and plagiarism, by adapting pedagogical practices. Jamieson emphasizes that AI is simply another tool, akin to computers or calculators, that can be integrated into teaching. She suggests using AI as a brainstorming or collaborative tool to enhance student learning, rather than viewing it as a threat to be policed. This approach aligns with broader pedagogical values, encouraging educators to trust students and teach them to use AI ethically and effectively. Jamieson also addresses labor issues within academia, critiquing the exploitation of contingent faculty and the mistrust embedded in surveillance technologies. She advocates for a “re-turn” to foundational teaching methods, emphasizing the process of writing—revision, invention, and critical thinking—as a way to engage students deeply with their work. Jamieson sees AI as an opportunity to strengthen writing education rather than undermine it.

- Carver, Joseph and Samba Bah. “Rehumanizing Higher Education: Fostering Humanity in the Era of Machine Learning.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20644.

- Carver and Bah examine the challenges and opportunities posed by artificial intelligence (AI), particularly generative AI, within higher education. They highlight the polarized attitudes toward AI, ranging from optimism about its potential to enhance research and efficiency to concerns about its impact on critical thinking and human values. They draw parallels to the “Science Wars” of the 1990s, which questioned the validity of soft sciences, and note the lack of consensus on AI policies among academics. The article emphasizes the historical development of AI, from Alan Turing’s foundational work to modern advancements in machine learning (ML) and deep learning, which have enabled AI to mimic human reasoning and solve complex problems like protein folding. However, the authors stress the “alignment problem,” a term referring to AI’s inability to fully understand and align with human values, leading to biased outcomes in areas such as hiring and criminal justice. They argue that higher education has a unique role in shaping the future of AI, not only through research and integration of AI tools but also by rehumanizing education. They advocate for a unified response to AI, one that prioritizes human values and addresses the existential implications of AI on education’s traditional goals, such as critical thinking and knowledge creation. Drawing on philosophical traditions like Ubuntu, an African philosophy emphasizing interconnectedness and community, the authors call for a reimagined higher education system that centers humanity, empathy, and collaboration. They conclude by urging educators to ensure that AI enhances rather than diminishes human potential.

- Liu, Larry. “AI and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Higher Education.” American Journal of STEM Education: Issues and Perspectives, vol. 4, 2024, pp. 16-26, https://www.ojed.org/STEM/article/view/7572.

- Liu explores how the rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence is challenging the legitimacy of higher education, defined as society’s belief in the necessity of college credentials for secure, middle-class jobs and social mobility. AI’s ability to perform tasks like essay writing, exam-taking, and personalized learning threatens to disrupt traditional educational roles, with some educators even leaving the profession due to its impact. While AI could potentially boost college legitimacy by displacing jobs and increasing demand for credentials, it also poses risks, such as overreliance on AI making students less engaged learners. The article identifies three key challenges: AI’s unique capabilities, government and employer shifts toward skills-based hiring over degree requirements, and the “enrollment cliff” caused by declining birth rates. Using sociological frameworks, Liu applies Jürgen Habermas’s concept of legitimation crisis, where the state’s ability to balance economic growth and welfare is strained, to argue that higher education’s role in maintaining capitalist legitimacy is at risk. Additionally, Randall Collins’s credential inflation theory suggests that the surplus of college graduates devalues degrees, creating social hierarchies rather than preparing workers for the labor market. Liu concludes that educators should embrace AI’s benefits while addressing its broader societal impacts, such as declining enrollment and political distrust in higher education.

- Fritts, Megan. “A Matter of Words: What Can University AI Committees Actually Do?” The Point Magazine, 12 May 2025, https://thepointmag.com/examined-life/a-matter-of-words/.

- Fritts discusses the profound challenges artificial intelligence (AI) poses to higher education, particularly in the humanities, as universities across the U.S. grapple with how to respond to the technology’s transformative impact. Fritts, a philosophy professor, details her experiences on AI response committees at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, where debates focus on issues like AI detectors’ accuracy, whether tools like Grammarly should be banned, and the ethical implications of students using AI for academic work. Central to these discussions is the tension between viewing AI as a tool for equity or efficiency and as a threat to human-centered education. She argues that the heart of the crisis lies in the humanities’ core mission: if the goal is to produce artifacts like essays or arguments, AI could soon replace human efforts. However, if the focus shifts to forming human persons through language and self-expression, AI becomes an existential threat by undermining the uniquely human connection between thought, language, and identity. Drawing on a philosopher like Ludwig Wittgenstein or the political theorist Alasdair MacIntyre, Fritts emphasizes that language is not just a tool but a formative part of human life, and relying on AI for communication risks eroding this essential aspect of humanity. She calls for radical policies to preserve the humanities by banning AI in classrooms and reclaiming the indispensability of human expression.

- Luckin, Rosemary, Mutlu Cukurova, Carmel Kent, and Benedict du Boulay. “Empowering Educators to be AI-Ready.” Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, vol. 3, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100076.

- Luckin et al. focus on the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education and emphasize the need for educators to become “AI-Ready.” AI is defined as the capacity of machines to simulate intelligent behavior, with applications ranging from learner-facing tools that adapt to individual needs to educator-facing systems that assist with tasks like grading and institutional support tools for resource management. Despite AI’s potential, its adoption in education lags behind other sectors due to challenges like ethical concerns, data limitations, and the complexity of educational ecosystems. The concept of AI Readiness involves understanding AI’s capabilities and limitations, particularly its lack of human-like qualities such as social intelligence and metacognition. The authors introduce the EThICAL AI Readiness Framework, a seven-step process (Excite, Tailor, Identify, Collect, Apply, Learn, Iterate) to guide educators and administrators in identifying challenges, collecting and analyzing data, and applying AI ethically. Case studies, such as one involving Arizona State University, demonstrate how this framework helps educators assess student learning behaviors and develop targeted interventions. The article concludes by stressing the importance of balancing AI’s strengths with human expertise to enhance education effectively.

- Ellerton, Wendy. “The Human and Machine: OpenAI, ChatGPT, Quillbox, Grammarly, Google, Google Docs, & humans.” Visible Language, vol. 57, no. 1, Apr. 2023, pp. 38-52, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/893661.

- Ellerton reflects on the evolving relationship between humans and technology, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of generative AI. Ellerton, a design educator, explores how tools like ChatGPT, Grammarly, and Quillbot are reshaping writing and communication, blending personal narrative with critical analysis. She discusses her experimentation with AI, highlighting both its potential to enhance creativity and collaboration and its limitations, such as the risk of misinformation and ethical concerns like authorship and bias. Using autoethnography, a research method that combines personal experience with cultural critique, she examines her own interactions with AI, revealing the tensions between human qualities like metacognition and emotional intelligence and the efficiency of machines. She advocates for a balanced approach, emphasizing the need to embrace human values and critical thinking while leveraging AI’s capabilities.

- Miller, Robin Elizabeth. “Pandora’s Can of Worms: A Year of Generative AI in Higher Education.” portal: Libraries and the Academy, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2024, pp. 21-34, https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2024.a916988.

- Miller considers the impact of generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Bard, and Bing Chat on higher education since their rapid introduction in late 2022. She discusses the varied reactions among educators, from alarm to cautious enthusiasm, and highlights the challenges of regulating and understanding these tools while students and colleagues simultaneously experiment with them. The piece uses Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation theory to frame the adoption process, categorizing users into groups like early adopters and laggards, and outlines the five stages of adoption: awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption. Miller also examines the spectrum of acceptable uses for AI, dividing them into “green light” tasks (low-resistance, repetitive work), “yellow light” tasks (cautious experimentation with expertise-related activities), and “red light” tasks (high-resistance creative or original work). The article raises ethical concerns, such as the potential for misinformation, copyright infringement, and depersonalization of communication, while also noting the practical benefits of AI as a tool for efficiency and learning. She emphasizes the ongoing challenges educators face in navigating the ethical, technical, and policy implications of generative AI, likening its introduction to opening Pandora’s Box, where hope remains the last and most enduring consequence.

- Norris, Christopher. “Poetry, Philosophy, and Smart AI.” SubStance, vol. 53, no. 1, 2024, pp. 60-76, https://doi.org/10.1353/sub.2024.a924142.

- Norris examines the debates surrounding AI’s role in poetry and creativity, drawing on his expertise in poetry, philosophy, and literary theory. He questions whether AI can genuinely think or create, arguing that AI-generated poetry is either a product of human creativity or a simulation. Norris engages with philosophical arguments, such as John Searle’s “Chinese Room” thought experiment, which posits that AI lacks consciousness and intentionality, rendering its outputs mere mechanical processes. He also considers the “extended mind” thesis, suggesting that tools like AI are extensions of human cognition, complicating distinctions between human and machine creativity. Norris discusses William Empson’s work on poetic ambiguity, linking it to the challenge of determining whether AI can capture the intentional depth of human poetry. The article concludes that while AI can mimic poetic forms, its impact on poetry will depend on its role as a tool to enhance rather than replace human creativity, emphasizing the enduring importance of judgment and intentional creativity in poetic endeavors.

- Laurent, Dubreuil. Humanities in the Time of AI. University of Minnesota Press, 2025, https://muse.jhu.edu/book/129366.

- Dubreuil’s Humanities in the Time of AI is the most challenging reading (to me) on this list. He presents a paradoxical optimism about the potential of AI to revitalize the humanities. He argues that while AI can perform tasks traditionally associated with humanistic research, such as summarizing, describing, or translating, these are not the ultimate goals of the humanities. Instead, he advocates for a maximalist understanding of scholarship, emphasizing creation, transformative signification, and the exploration of the unsaid. He distinguishes between invention, which reorganizes existing knowledge, and creation (poiēsis), which emerges from contradictions and impossibilities, suggesting the latter as the true domain of the humanities. Dubreuil critiques both conservative and progressive approaches to humanistic inquiry, arguing that the humanities must engage in a dialogical endeavor that considers the past, present, and future without reducing scholarship to tradition or moral indictment of historical eras. He also explores the relationship between AI and human cognition, noting that AI is not a separate entity but an extension of human thought, trained on vast datasets of human artifacts. Dubreuil emphasizes that while AI can simulate creativity, it lacks true interpretive and creative capacities, which remain the province of the humanities. He calls for a redefinition of the humanities that embraces their role in interpreting and creating meaning, positioning them as a counter to the standardized, algorithmic thinking of AI. Dubreuil critiques the superficial dismissal of Plato’s concerns about writing in the Phaedrus, arguing that these concerns resonate with contemporary debates about AI’s impact on cognition and memory. He challenges the notion that AI is merely a neutral tool, highlighting its potential to reshape human thought and creativity. Dubreuil also examines the ethical dimensions of AI, cautioning against the reduction of ethics to utilitarian decision-making and emphasizing the importance of critical interpretation over descriptive scholarship. He advocates for a maximalist vision of the humanities, one that embraces complexity, creativity, and the unique capacities of humanistic inquiry in the face of technological advancements. Dubreuil sees AI as both a challenge and an opportunity to redefine the humanities’ role in fostering critical thinking, interpretive depth, and intellectual exploration.