This is the fifty-sixth post in a series that I call, “Recovered Writing.” I am going through my personal archive of undergraduate and graduate school writing, recovering those essays I consider interesting but that I am unlikely to revise for traditional publication, and posting those essays as-is on my blog in the hope of engaging others with these ideas that played a formative role in my development as a scholar and teacher. Because this and the other essays in the Recovered Writing series are posted as-is and edited only for web-readability, I hope that readers will accept them for what they are–undergraduate and graduate school essays conveying varying degrees of argumentation, rigor, idea development, and research. Furthermore, I dislike the idea of these essays languishing in a digital tomb, so I offer them here to excite your curiosity and encourage your conversation.

The first seminar that I had with Professor Tammy Clewell was “Methods in the Study of Literature.” The second was “Social Theory.” This was an enjoyably challenging seminar in which Professor Clewell encouraged us to explore the them in our specific fields of study. In my case, I researched the exchange of cultural capital in Science Fiction.

One of the best lessons that I gained from this class happened years afterward. While finishing my dissertation, I sent a lot of publishable-length manuscripts around for consideration. One of those was the longer version of the presentation-length draft included below (I will publish the full length final version on Friday as “Prize Based Cultural Capital Exchange and the Destabilization of the Science Fiction Genre”). In the rejection that I received, a number of factual errors relating to the lore section on the cyberpunks were pointed out by the journal editor. It was a hard lesson in verification and citation that I will not soon forget, and one that I share with my students to drive home the importance of corroboration.

Due to a number of problems with this essay, including the inaccurate lore, I do not recommend citing this work. Instead, it is offered as a reminder for citation and a resource of ideas and sources.

Jason W. Ellis

Professor Tammy Clewell

Social Theory

17 November 2008

Cultural Capital, Market Capital, and the Destabilization of the Science Fiction Genre Presentation

Michael Chabon, a recognized and celebrated American author best described as mainstream with an admittedly healthy interest in genre fiction, routed the competition in two of the three most prestigious Science Fiction (SF) genre awards with his 2007 alternate history novel, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. As an alternate history novel, it appeared in the SF section of bookstores, as well as the mainstream section due to Chabon’s widespread recognition as an eminent American author of literature, not genre literature. Also, the cross pollination of Chabon’s work in the SF ghetto is not wholly unique, because Philip Roth, another recognized American author, published his own alternate history novel, The Plot Against America, three years prior. However, what sets Chabon’s novel apart from Roth’s, is that The Yiddish Policemen’s Union swept the two big SF genre superprizes, the Hugo and Nebula, and arrived in second place to Kathleen Ann Goonan’s In War Times for the John W. Campbell Award. In order to evaluate the linkages connected to the Hugo Award, it is necessary to employ a theoretical framework that goes beyond the operations of real capital into the realm of cultural capital, such as that offered by James English in his work, The Economy of Prestige. Furthermore, Chabon’s recent successes raises questions about the purpose of the Hugo Award in relation to the SF cultural economy, the transfer of real capital to and from SF authors, and the meaning of SF in general. In this paper, I argue that Chabon’s Hugo Award triumph destablizes the meaning of SF as a genre due to the transfer of cultural capital and real capital away from the SF archive.

English adroitly theorizes the exchange and movement of cultural capital via prizes and awards in his 2005 book, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Capital. In this work, English expands Pierre Bourdieu’s developing “economic calculation to all the goods, material and symbolic” (qtd. in English 5). Bourdieu’s project refers to “cultural capital,” or an intangible, yet realizable, economy of cultural exchange. English chooses the prize as his object of study, and argues convincingly that prizes are one such signifier of cultural capital exchange. Coupled to English’s primary claim, he develops three significant supporting assertions supported by prize data and a number of regional and superprize cases (such as the Noble Prize for Literature and the Man Booker Prize), which are: 1) prizes are a widespread cultural practice, 2) the number of prizes has proliferated and prizes beget other prizes through virtual modeling or cloning, and 3) prizes are made possible by complex machineries and assemblages of people and distributed work, which have a material cost often in excess of the prize bestowed. It is from the third point that English reveals the cultural capital conveyed by prizes and awards, because it is the intangible but easily recognized priceless value of awards. Essentially, there are economies of cultural capital that do not readily translate into material capital, and cultural capital is circulated within fields where that particular cultural capital is meaningful to those persons within that field.

Throughout The Economy of Prestige, English primarily uses examples of juried prizes, which feature jurors whose own cultural capital becomes part of the complex exchange between prize and winner. However, I want to discuss a special case, which English does not address in his book. My interest focuses on superprizes that are awarded based on the conclusion of a popular vote rather than the decision of a small group of recognized jurors. Specifically, I’m concerned with the oldest, extant SF genre award, the Hugo.

The Science Fiction Achievement Awards, or more commonly known as the Hugo Awards in honor of the pulp SF editor, Hugo Gernsback, are an annually bestowed set of awards created in 1953 at the suggestion of SF fan Hal Lynch and modeled after the National Film Academy Awards, or Oscars (Nicholls 595). It is an early example of prize proliferation, because it replicates the voting and spectacle aspects of the Oscar superprize model as a means to elevate the prestige of popular, yet marginalized, SF genre literature. Additionally, the Hugos establishment as an institution within the SF genre operates in the same way that English says, “prizes have always been of fundamental importance to the institutional machinery of cultural legitimacy and authority” (37). The Hugos legitimate popularly regarded works of great SF through its authority as the first superprize in the genre. Furthermore, the Hugos, like the prizes that English studies, acquire greater cultural capital through scandal. English argues that:

Far from posing a threat to the prize’s efficacy as an instrument of the cultural economy, scandal is its lifeblood; far from constituting a critique, indignant commentary about the prize is an index of its normal and proper functioning. (208).

The Hugos follow this counterintuitive “proper functioning” that English describes. The award began quietly enough, but following an initial sophomore setback in which it wasn’t administered and awarded again until 1955, the controversy began. The most recognized controversy throughout the history of the Hugos is best described by Peter Nicholls, when he writes:

The Hugos have for many years been subject to criticism on the grounds that awards made by a small, self-selected group of hardcore fans do not necessarily reflect either literary merit or the preferences of the sf [sic] reading public generally; hardcore fandom probably makes up less than 1 per cent of the general sf readership. (596)

The self-selection of voting members is problematic, because they are, unlike the juries that English discusses, a collection of individuals without discrete and recognized cultural capital to add to the award. However, the popular aspect of the Hugos supplements the popular aspect of SF literature. SF literature connects with a wide audience in many different ways through a myriad of vectors. SF, like any literature, is not homogenous. The themes, ideas, and narratives in SF literature are as varied as its audience. I conjecture that it is this egalitarian and popular aspect, further embedded in SF following the Second World War with the increase in women SF writers and readers as shown by Lisa Yaszek and others, as well as the explosion of the New Wave, that connected SF to a wider and energized audience.

With the preceding controversy of the popular vote as an ever-present background to the Hugos, other controversial events took place in the 1980s, which added to the prestige of the SF genre superprize. The first recognized controversy involved the next big thing, building on the successes and innovations of New Wave SF, but integrating in the extrapolative potential of contemporary developments in computer technology and global capital. The cyberpunks didn’t so much as land as jack-in, and the way that they did this has since become lore. At the 1985 Worldcon, William Gibson and a coterie of his compatriot writers, Bruce Sterling and Pat Cadigan, stepped out of a stretch limo wearing ripped jeans, black leather jackets, and the immediately recognizable mirrorshades. Gibson’s punk antics and disregard of the traditional suit-and-tie sensibility of the Hugo Awards ceremony elevated his status and the cyberpunk movement he represented. However, this only solidified what he accomplished by winning the three major SF awards for his 1984 novel, Neuromancer–the Hugo, Nebula, and the John C. Campbell Award. In the following year, the only Hugo Award refusal took place when Judy-Lynn del Rey’s widow, Lester del Rey, refused her 1985 Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor, “on the grounds that she received the accolade only because of her death” (Mallett and Reginald 58). And a final notable example of Hugo Award controversy took place in 1989 when the Worldcon committee barred Stephen Hawking’s popular science work, A Brief History of Time (1988), from the potpourri nonfiction category (Nicholls 596).

The Hugos have developed a considerable amount of cultural capital by English’s model, but the award is unlike those he analyzes. He establishes in his analysis of that scandal and gamesmanship strategies play an integral part in the development of awards and their followings, but in what he calls, “the higher, ‘art’ end of the art-entertainment spectrum” (English 189). I do not agree with his selection of prizes, because he characterizes them as “somewhat more elaborate” than supposedly lesser prizes (English 189). The sophistication of the Hugo Award mail-based balloting system, single transferable ballot counting, the spectacle of the annual awards ceremony in a different international host city, and the commentary, bookmaking, and reflecting on the awards in magazines, fanzines, and blogs, is in my opinion of sufficient elaborateness to warrant critical evaluation. Furthermore, the Hugo Awards represent a special case that English does not explore, which is a popular vote award that carries within its literary community a greater prestige than any other award. In fact, the Hugo Awards signify an attempt at greater transparency and egalitarian choice than that offered by English’s example of the Man Booker Prize. Additionally, its egalitarianism increases its complexity due to its broad base of voting readers and the ensuing machinery of influence and promotion.

Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union recent win of the 2008 Hugo Award for Best Novel further exemplifies the special case of the Hugo Awards. SF readers and critics overwhelmingly welcomed Chabon and his work to the SF ranks with the publication of his sixth novel. However, Chabon, like other well-regarded mainstream, or dare I say literary, authors that have ventured across the genre divide has maintained a playful, but arm’s length distance from being labeled an SF author. Chabon is masterful at sidestepping genre identification, such as when he writes in his introduction to The Best American Short Stories 2005 that, “I have argued for the commonsense proposition that, in constructing our fictional maps, we ought not to restrict ourselves to one type or category” (xvi). He argues for a non-market supportable writing free-for-all that obviates any need on his part to assume a genre alignment. Furthermore, he playfully critiques the contemporary usage of genre in his introduction to McSweeney’s Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories, when he writes, “I suppose there is something appealing about a word that everyone uses with absolute confidence but on whose exact meaning no two people can agree. The word that I’m thinking of right now is genre, one of those French words, like crêpe, that no one can pronounce both correctly and without sounding pretentious” (ix). To be fair, his analysis of genre construction is insightful, but it is impossible for him to ignore the claim that he became a SF writer with the publication of The Yiddish Policemen’s Union.

So, what does it mean for a non-self-identified SF writer to win the most prestigious SF award, or conversely, what does it mean for the most prestigious SF award to be given to a self-identified writer without genre classification, or more harshly association? There are two considerations to be made regarding the exchange of capital in the case of Chabon’s Hugo Award win. The first has to do with the prestige exchange between Chabon, the Hugo Awards, and the archive of SF works. Were the Hugo voters eager to add a prestigious, non-genre author, because it, in a way, validates SF as more than genre literature? I cannot answer that, but I can approach the question after the fact. Mainstream entrance into the SF archive creates slippage, and undermines what we mean when we say, “Science Fiction.” It illustrates a problem where accomplished writers, such as Chabon, may enter the genre at will, without acknowledgement, and make off with one of the greatest bearers of SF cultural prestige. Turning the issue around, Chabon walks a fine line as a legitimated literary writer, who stands to lose that prestige if identified as a genre writer. This is not always the case, as evidenced by Doris Lessing, an admitted SF writer and author of the Canopus in Argos: Archives five novel sequence, who won the 2007 Nobel Prize for Literature. Though, this is a stark exception to the rule of ghettoization as evidenced by the early struggles of Kurt Vonnegut for literary legitimacy. Genre fiction carries heavy markers for literary hopefuls that are most assuredly on the minds of such authors, and it is not surprising that Chabon hedges his bets in his authorial identification in spite of the SF accolades bestowed on his works. However, Chabon’s success and conveyance of prestige away from the SF archive reveals the other and arguably more important consideration of exchange–monetary capital and lost book sales for unpretentious SF authors who can only dream of advances comparable to those Chabon receives for his work. But, what of genre? I will have to save this much more weighty question for my longer paper, but I will say that Chabon and other extraordinary non-SF winners of the Hugo may point the direction to a far future–a Science Fiction story in itself–one in which the pragmatic reality of “the law of genre” is no more.

Works Cited

Best, Joel. “Prize Proliferation.” Sociological Forum 23.1 (2008): 1-27.

Chabon, Michael. Introduction. The Best American Short Stories 2005. Ed. Michael Chabon. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

—. Introduction. McSweeney’s Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories. Ed. Michael Chabon. New York: Vintage Books, 2004. ix-xv.

—. The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

English, James F. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 2005.

Mallett, Daryl F. and Robert Reginald. Reginald’s Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: A Comprehensive Guide to the Awards and Their Winners. San Bernardino, CA: The Borgo Press, 1993.

Menard, Louis. “All That Glitters; Literature’s Global Economy.” The New Yorker 26 December, 2005: 136.

Nicholls, Peter. “Hugo.” The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Eds. John Clute and Peter Nicholls. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994. 595-600.

North, Michael. Rev. of The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value by James F. English. Modernism/modernity 13:3 (2006): 577-578.

Polumbaum, Judy. Rev. of The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value by James F. English. Journal of Communication 57 (2007): 179-181.

Showalter, Elaine. “In the Age of Awards.” Times Literary Supplement 3 March 2006: 12.

Wijnberg, Nachoem M. Rev. of The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value by James F. English. Journal of Cultural Economics 30 (2006): 161-163.

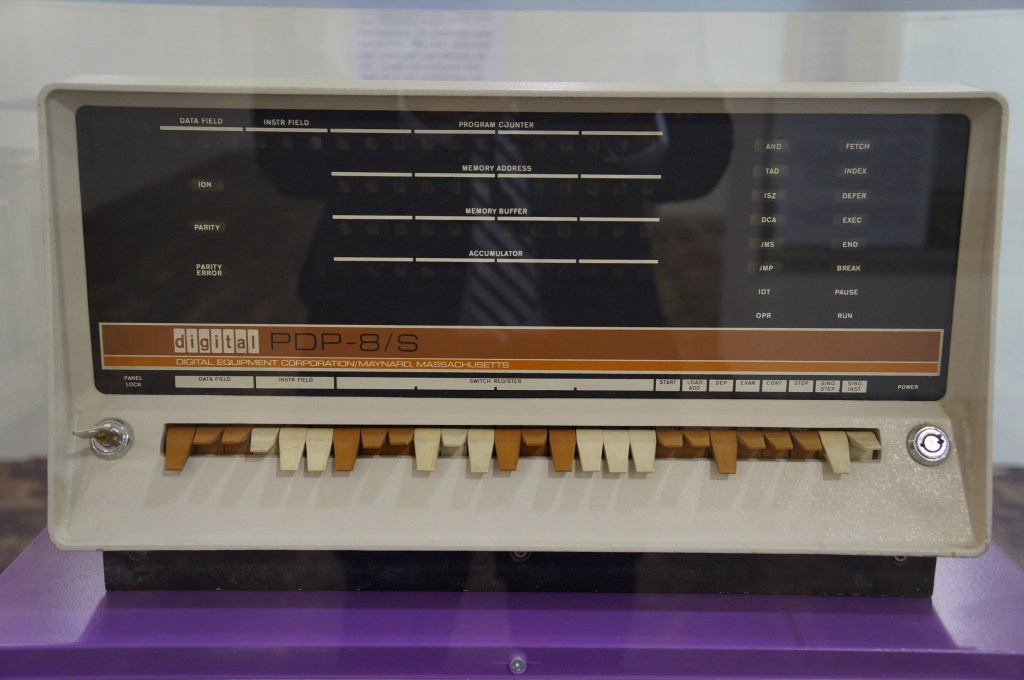

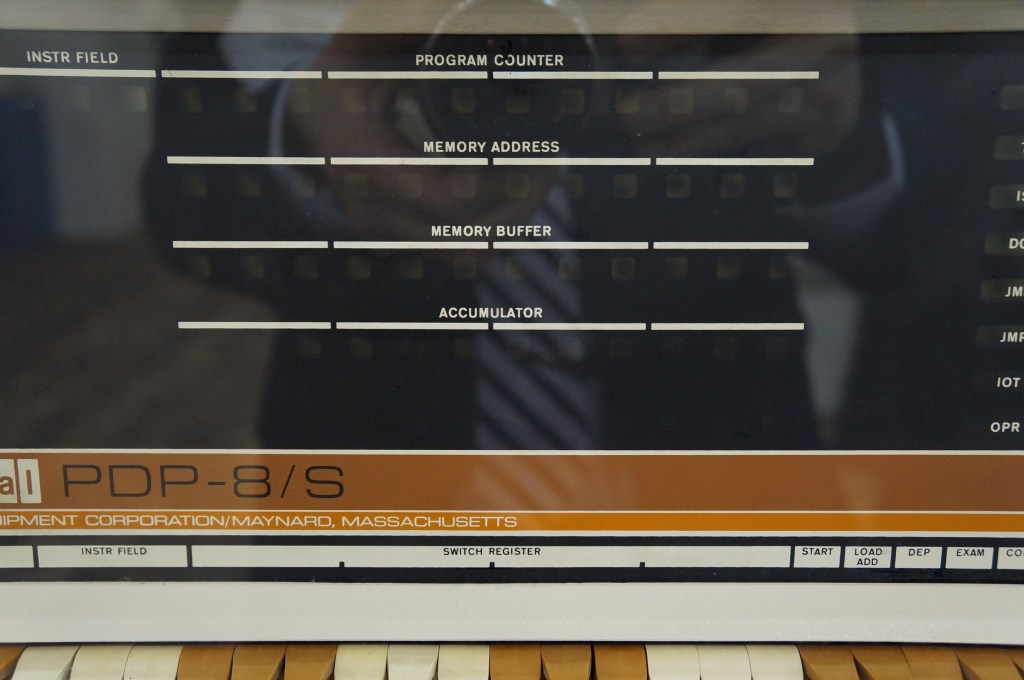

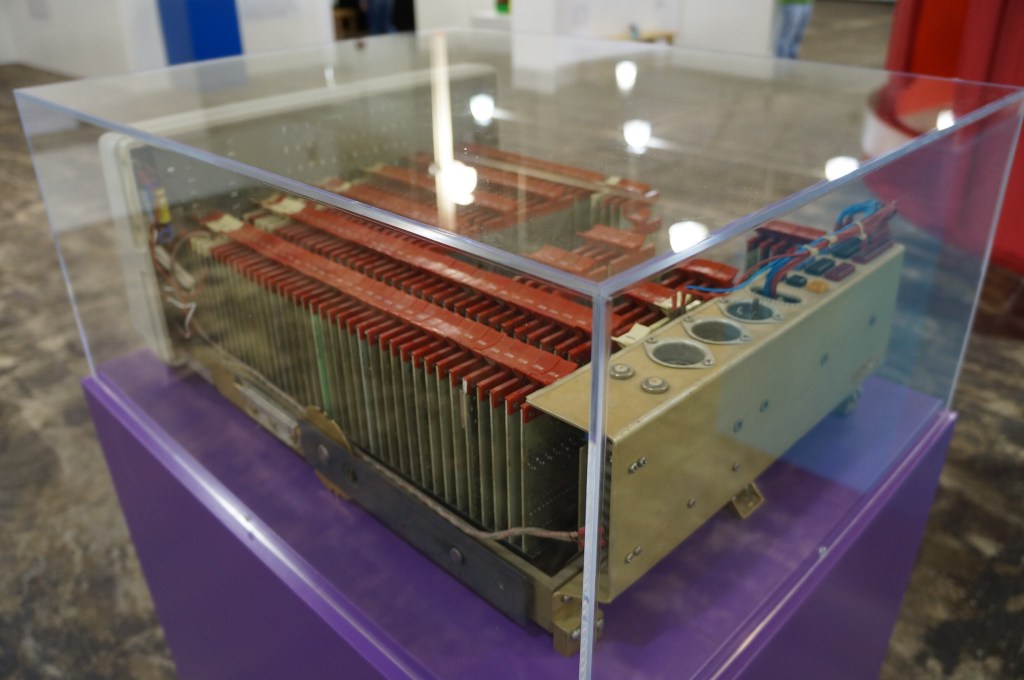

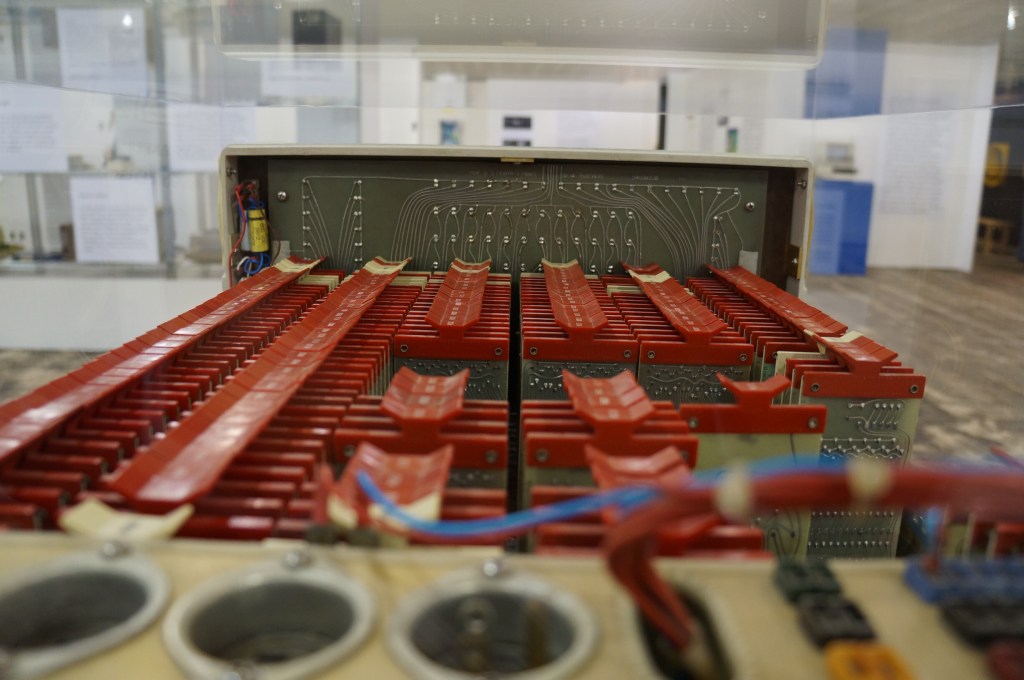

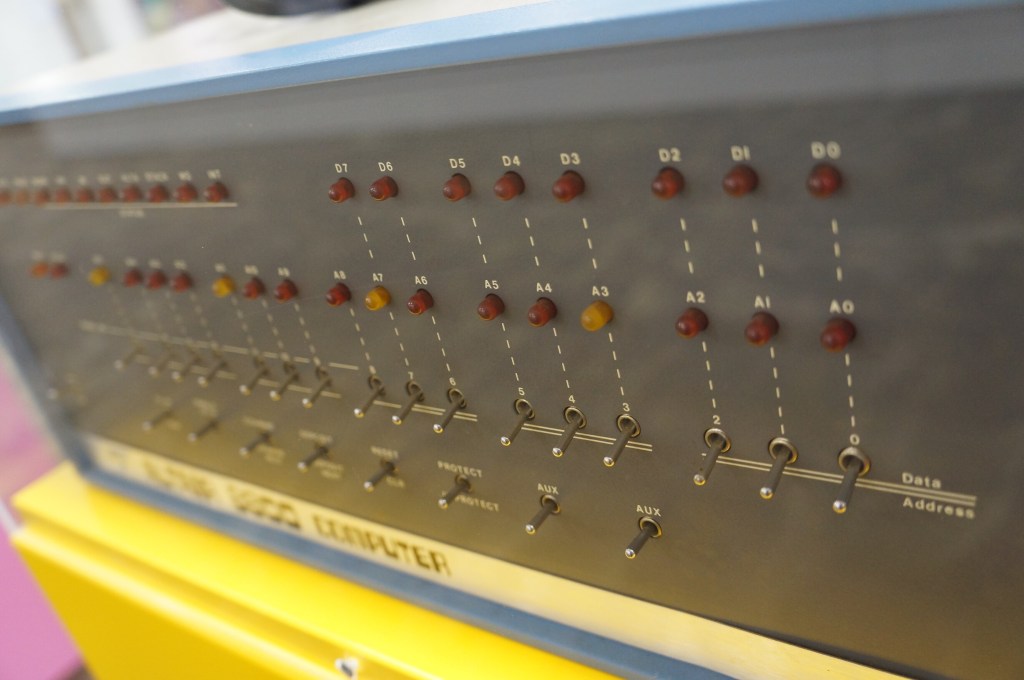

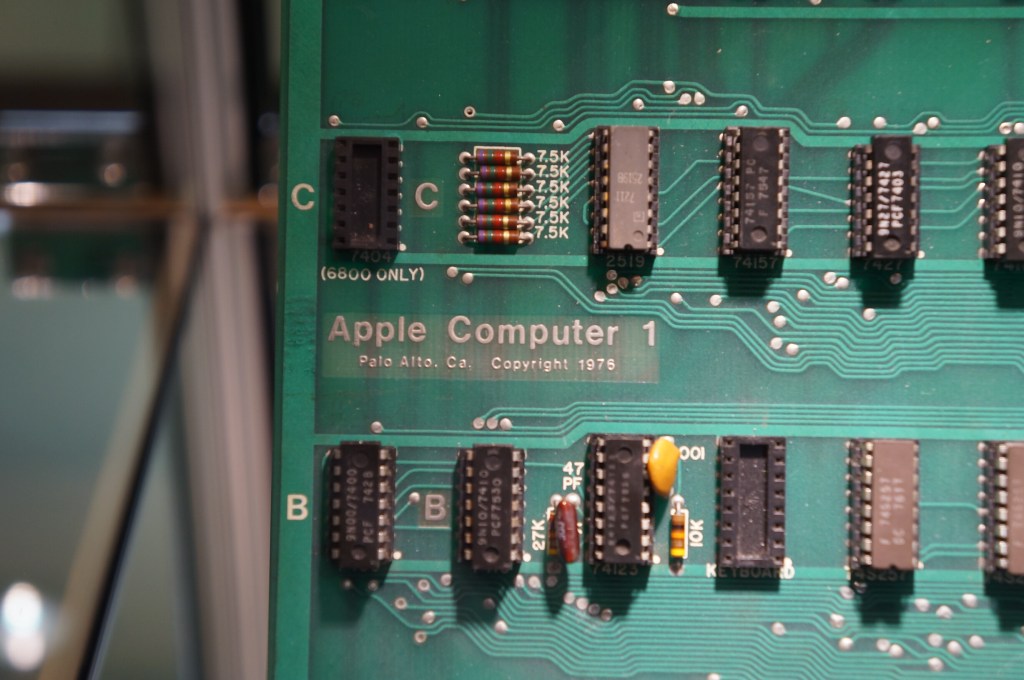

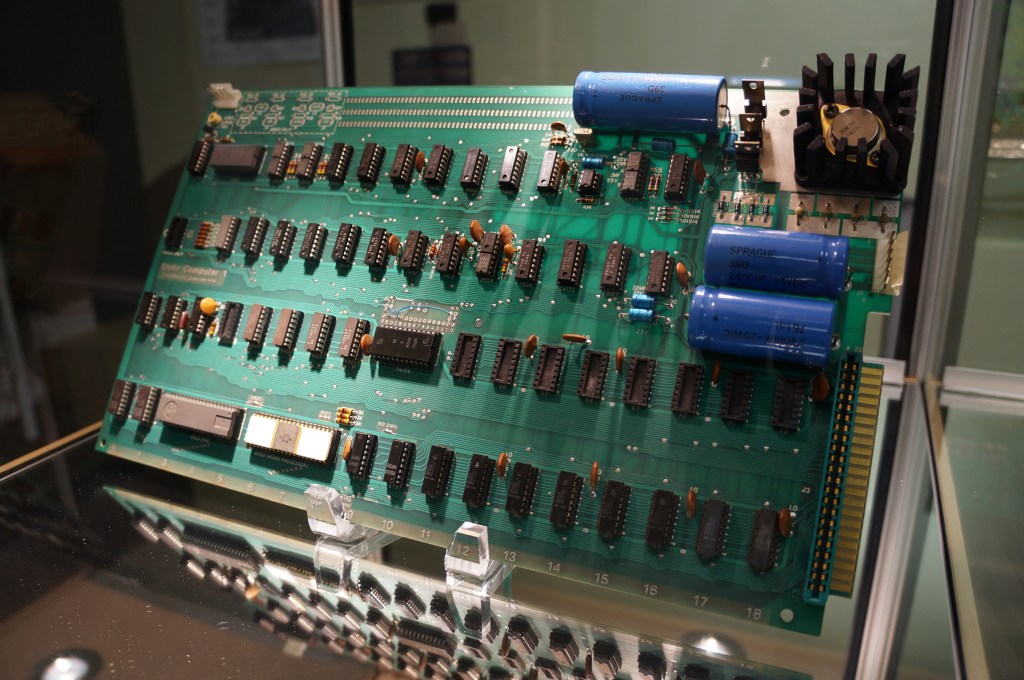

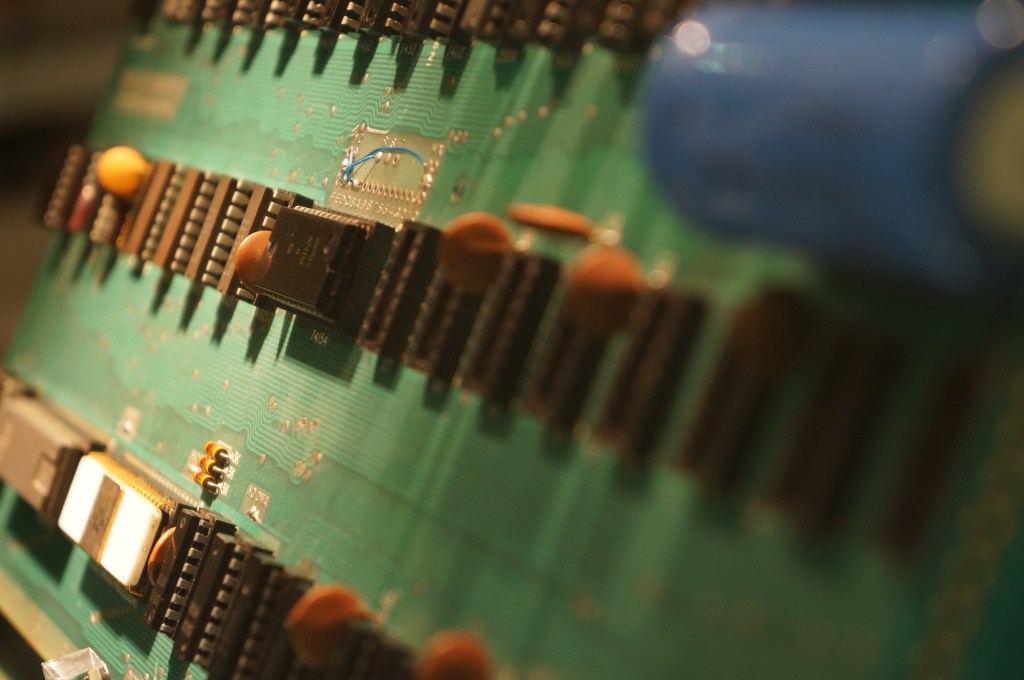

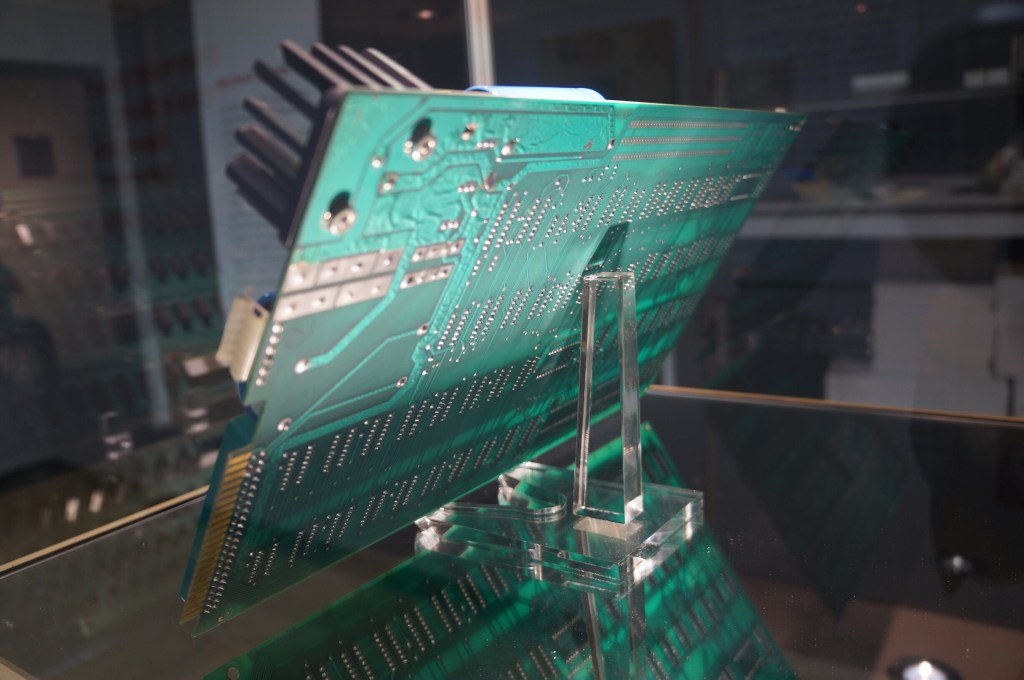

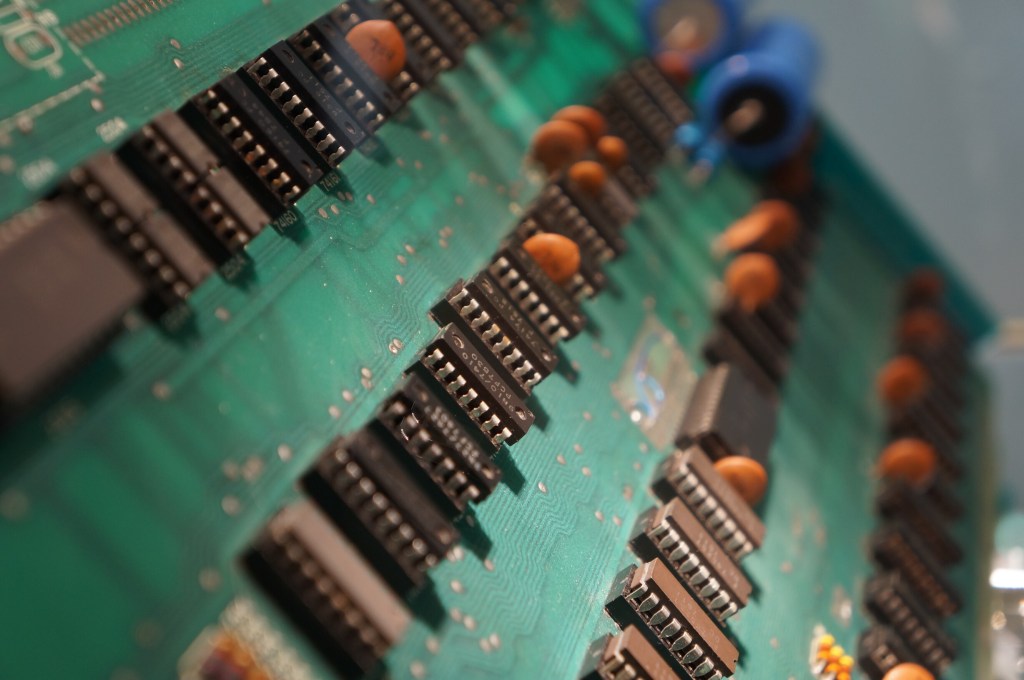

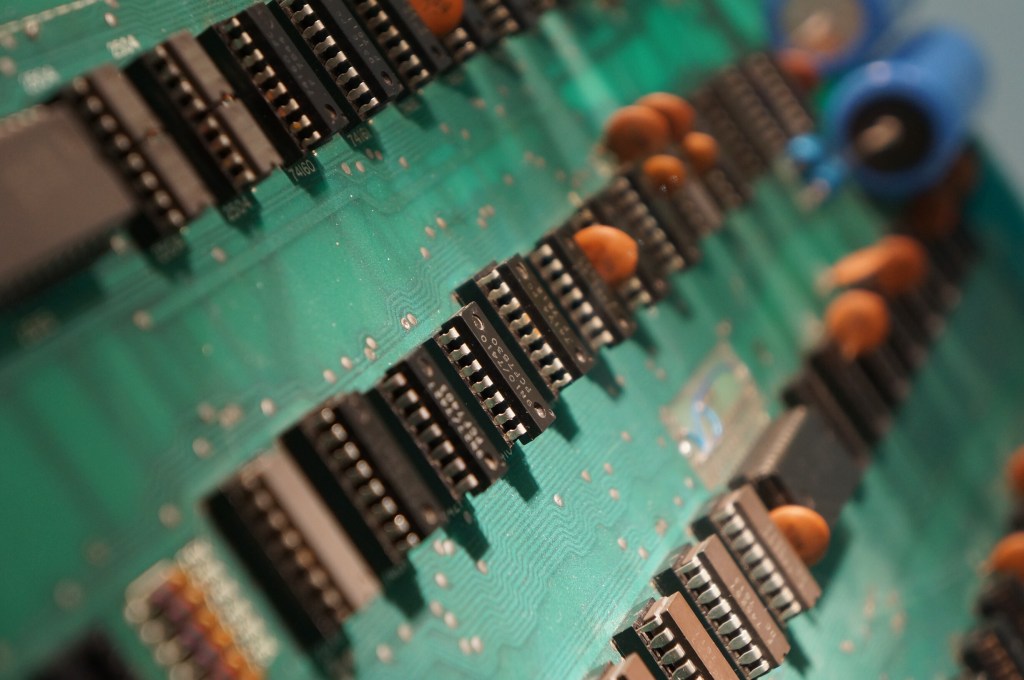

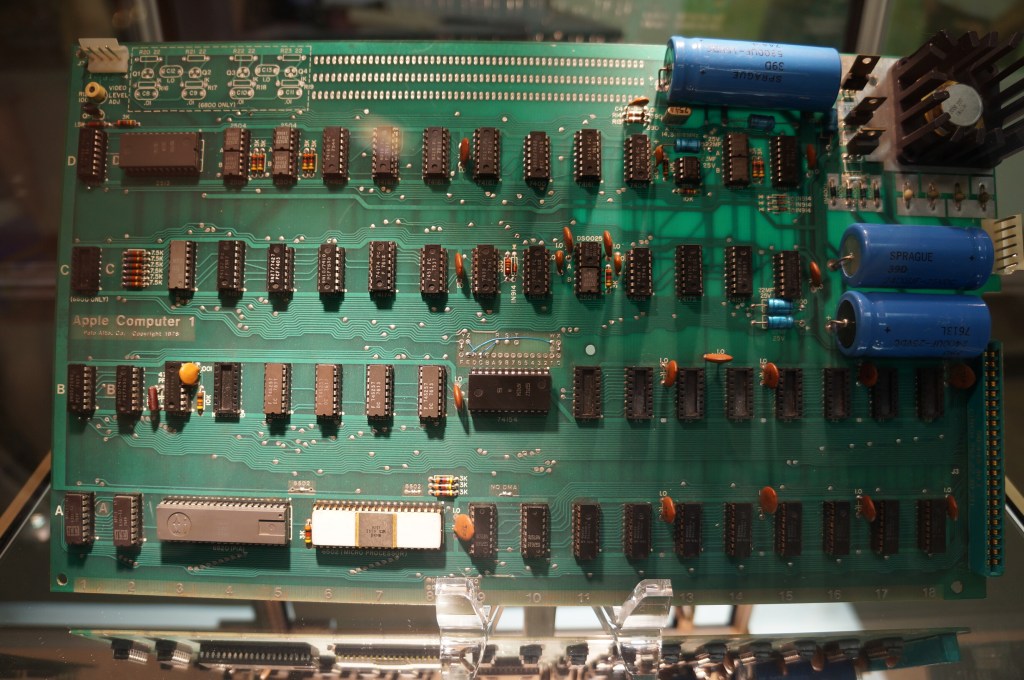

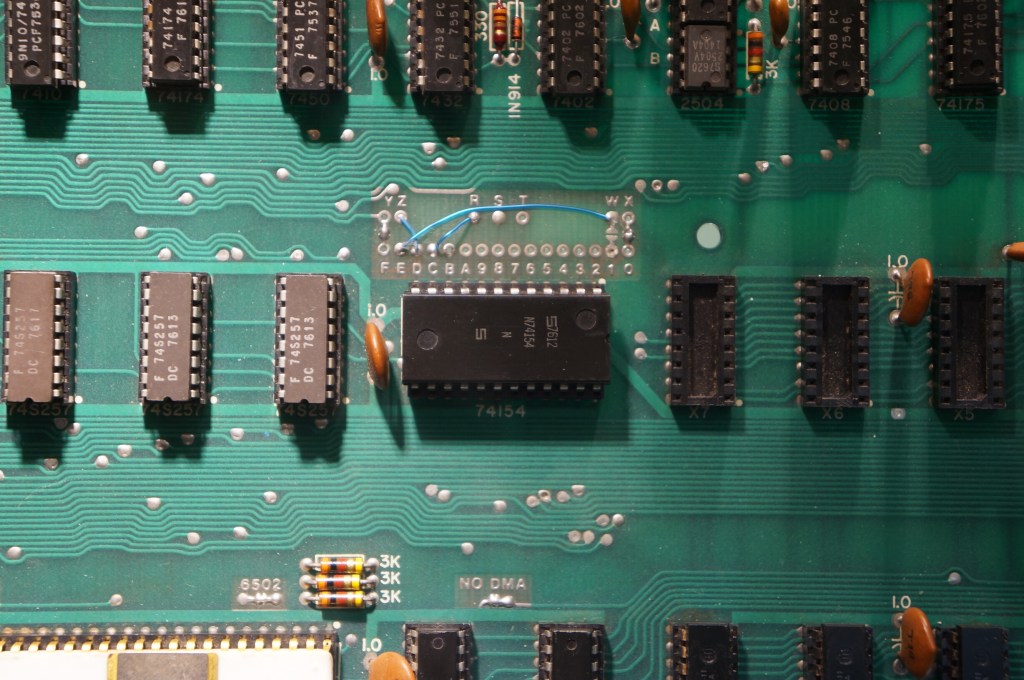

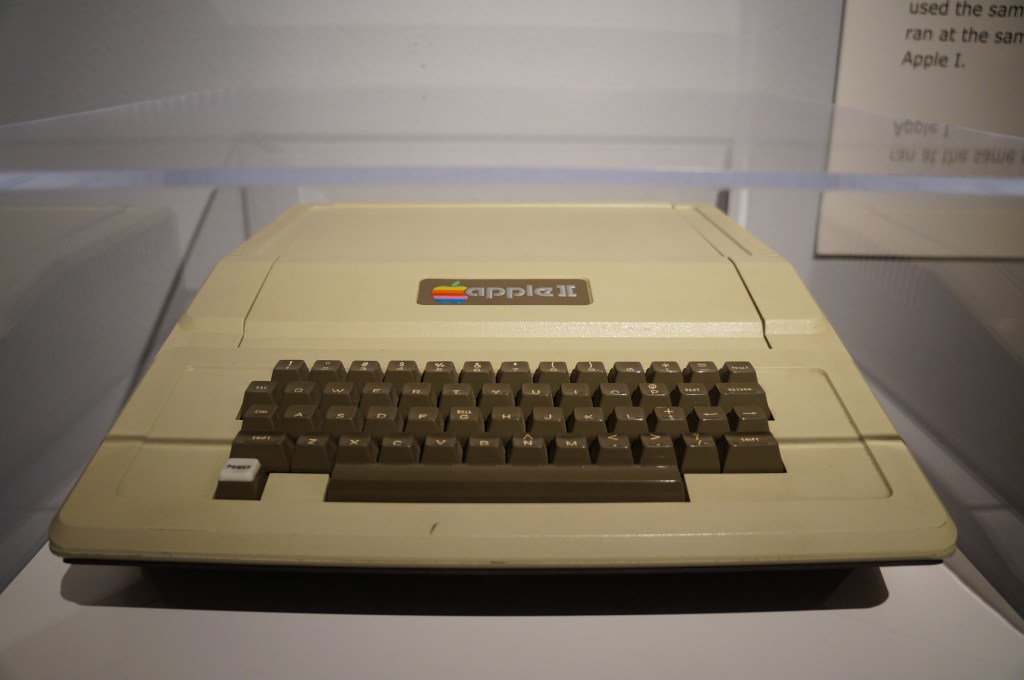

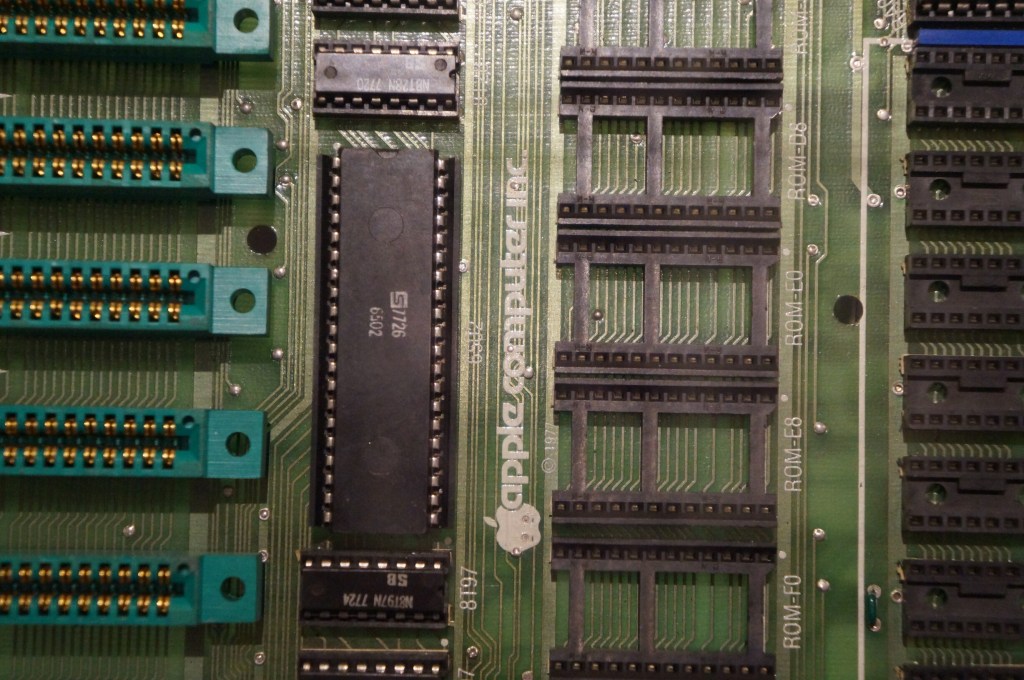

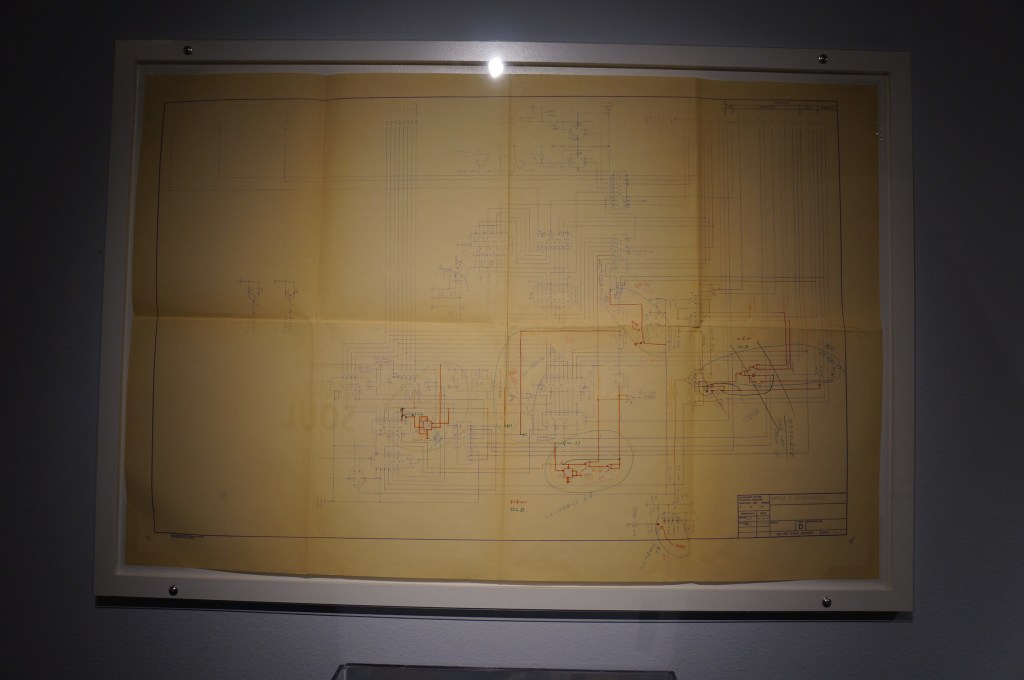

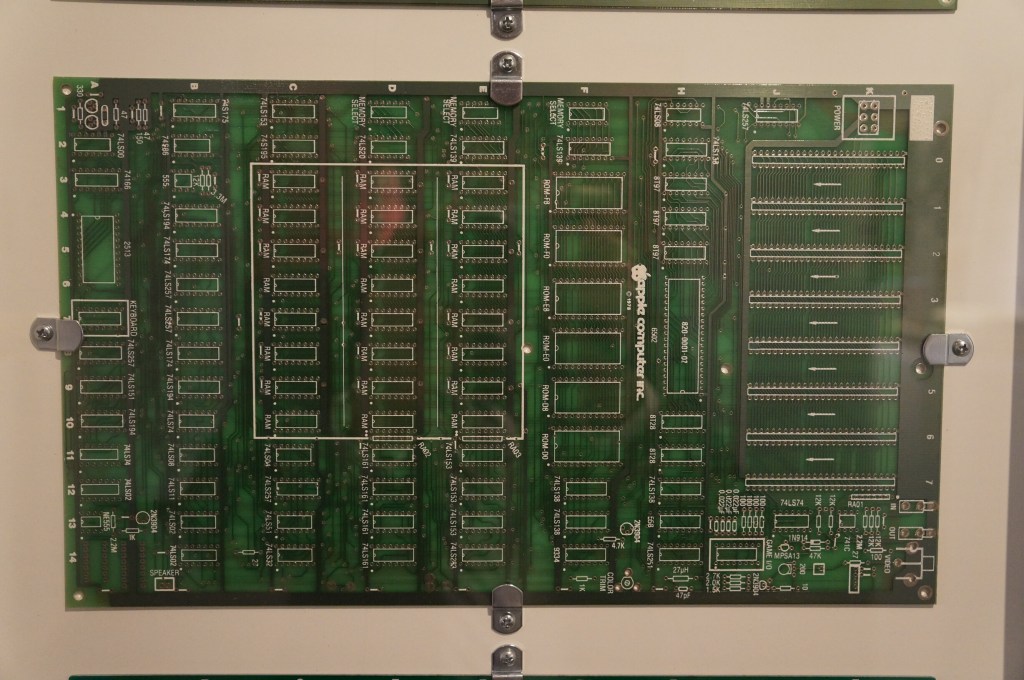

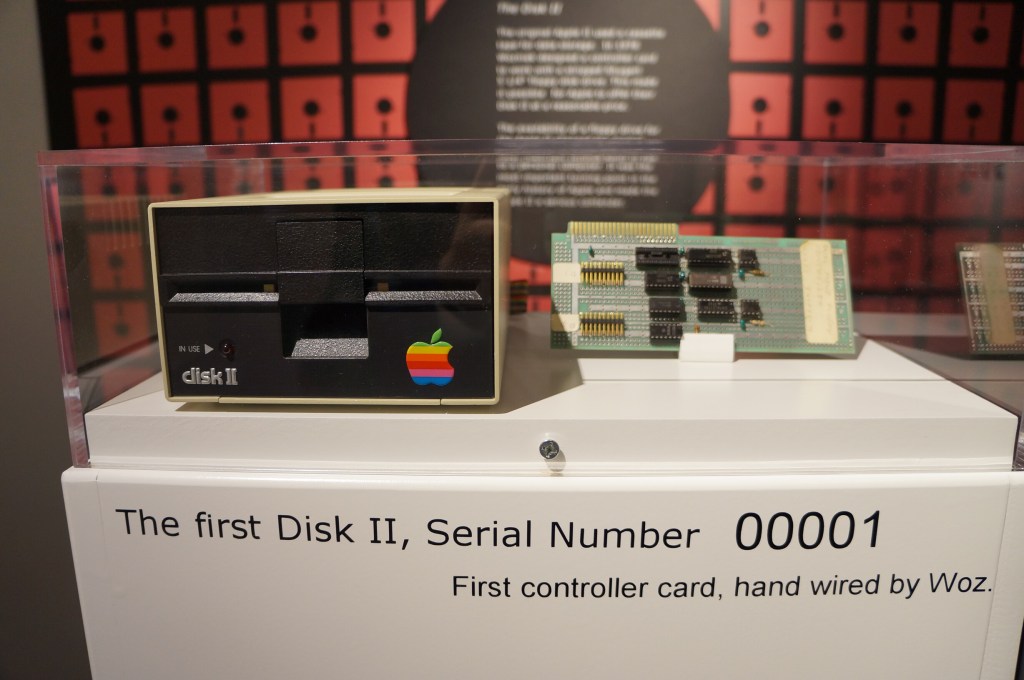

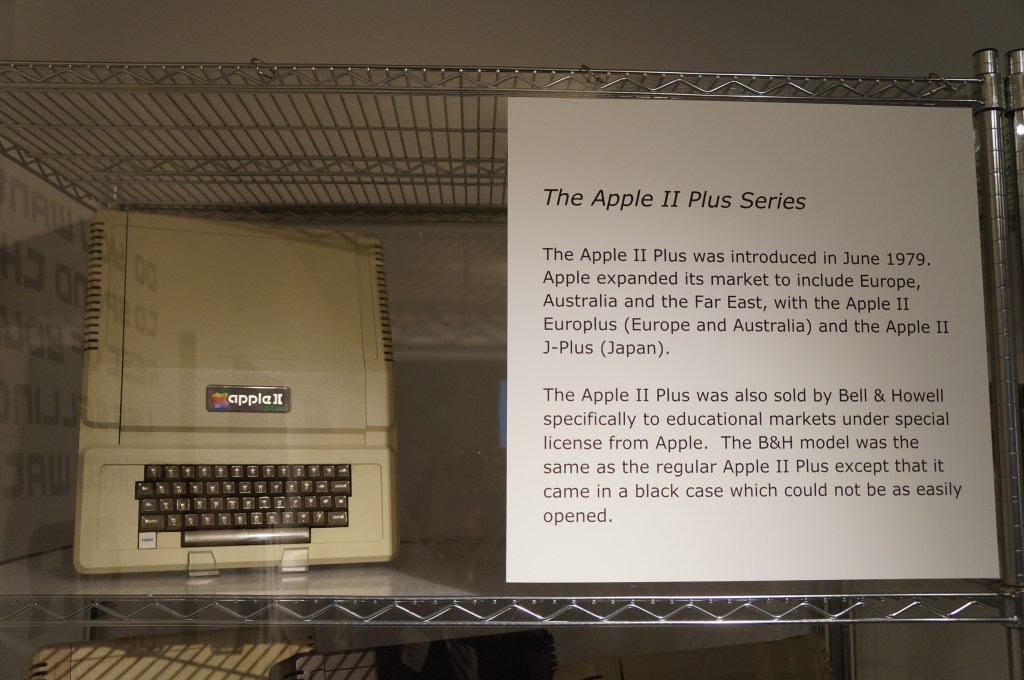

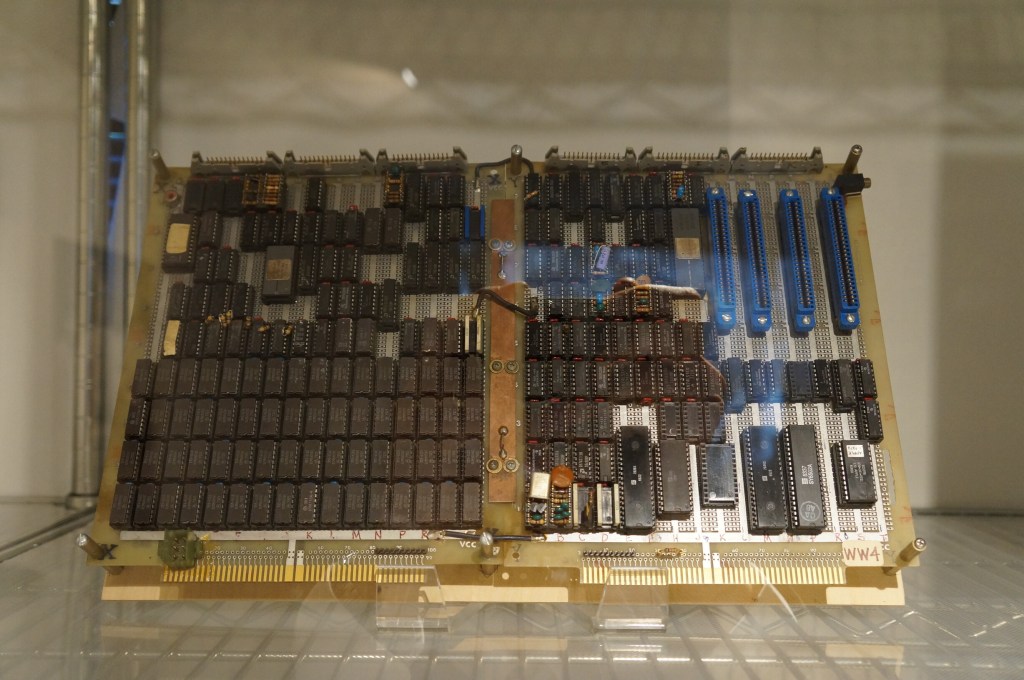

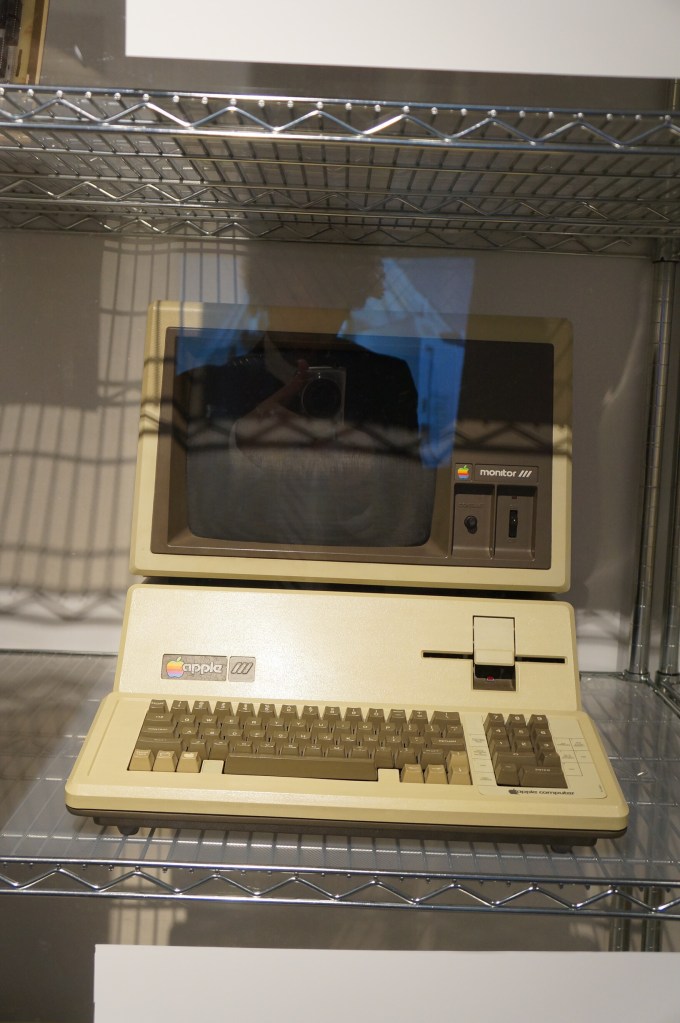

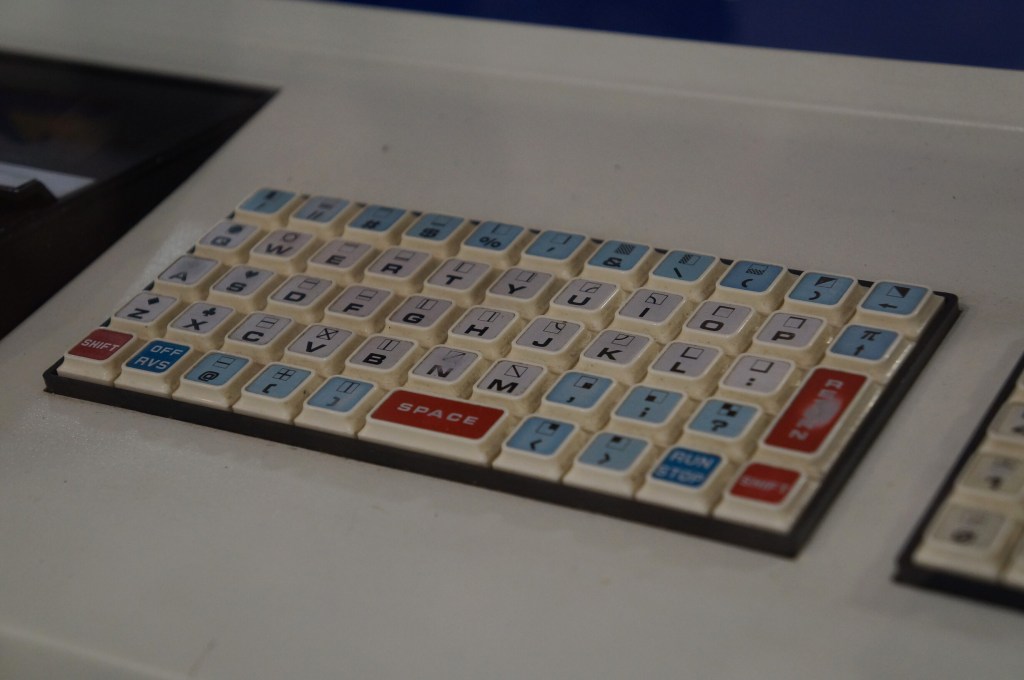

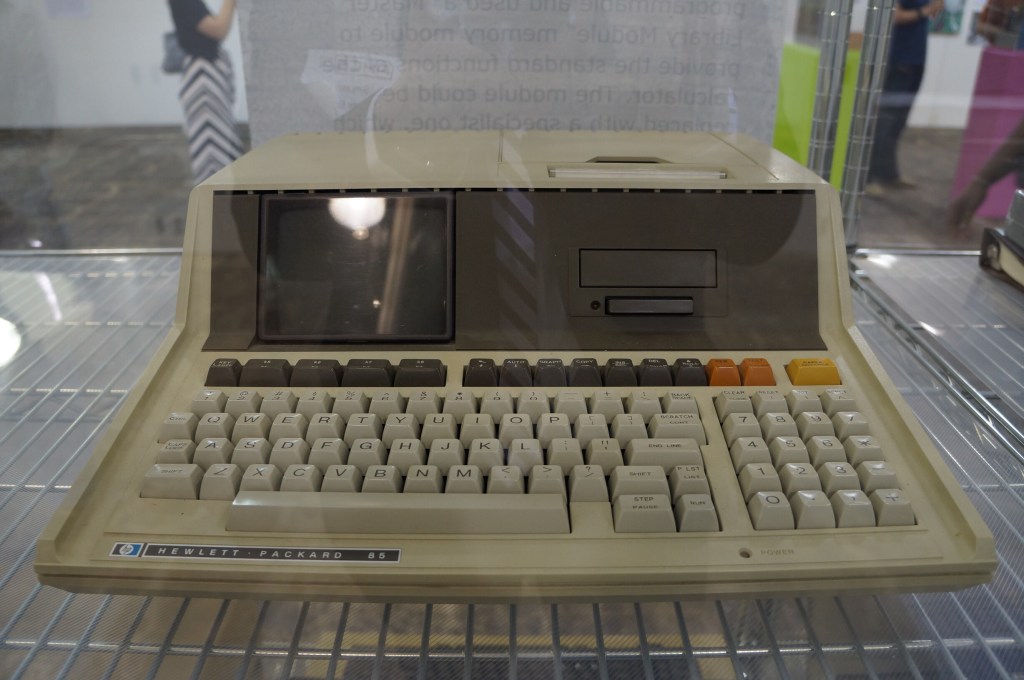

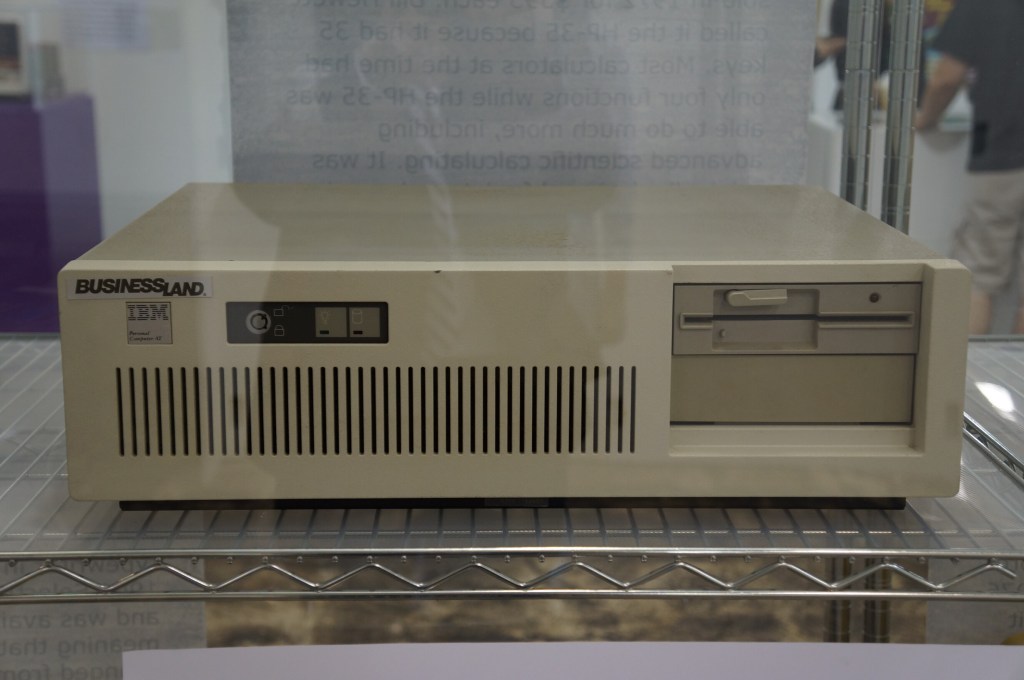

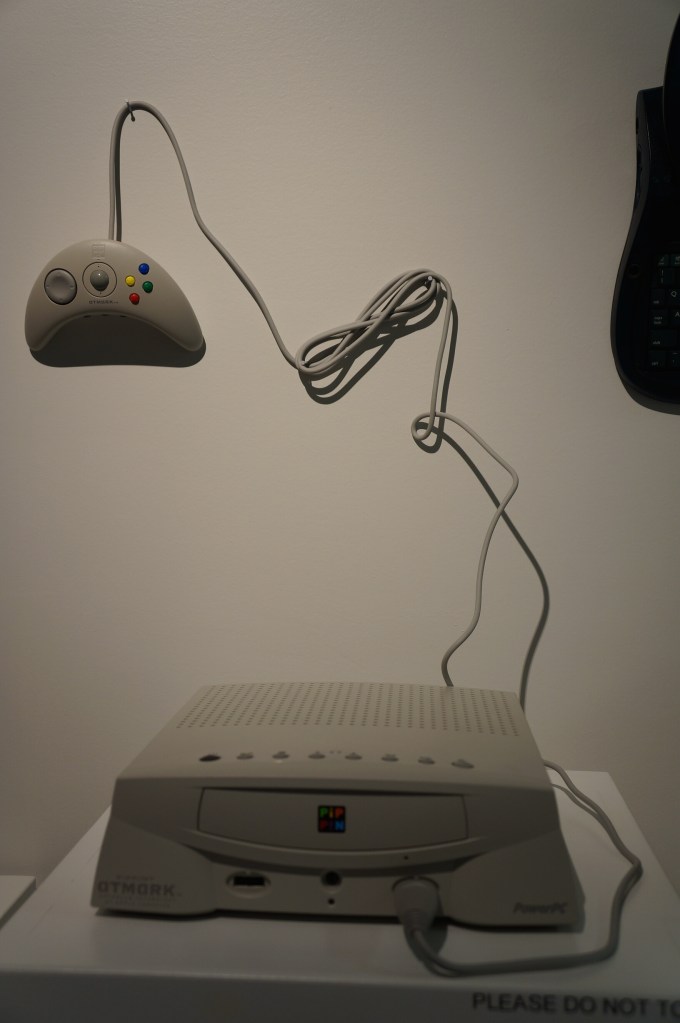

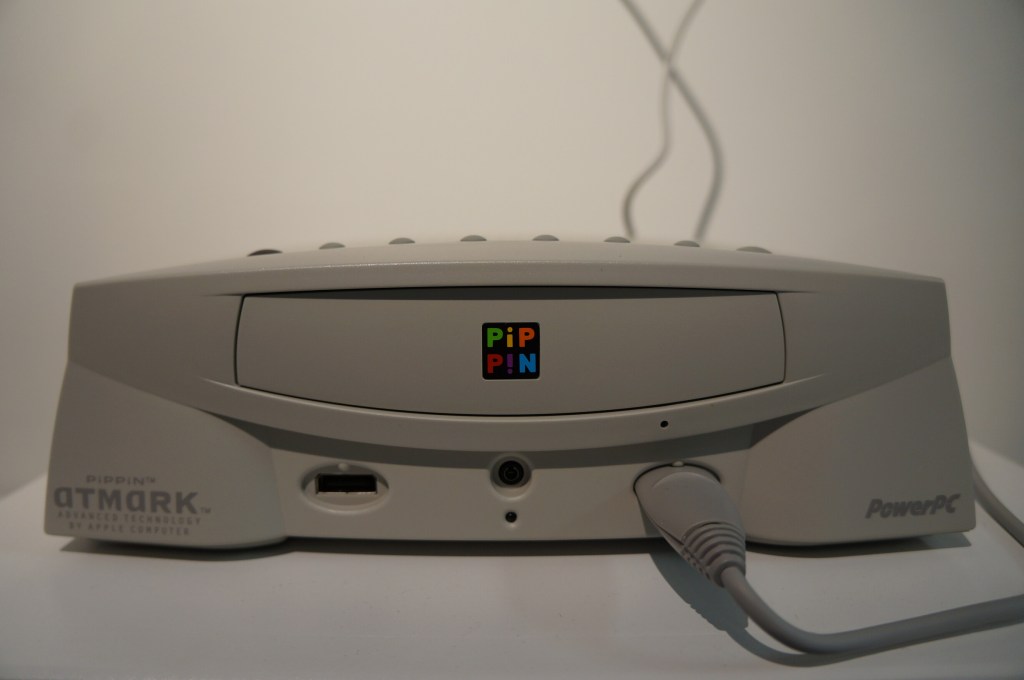

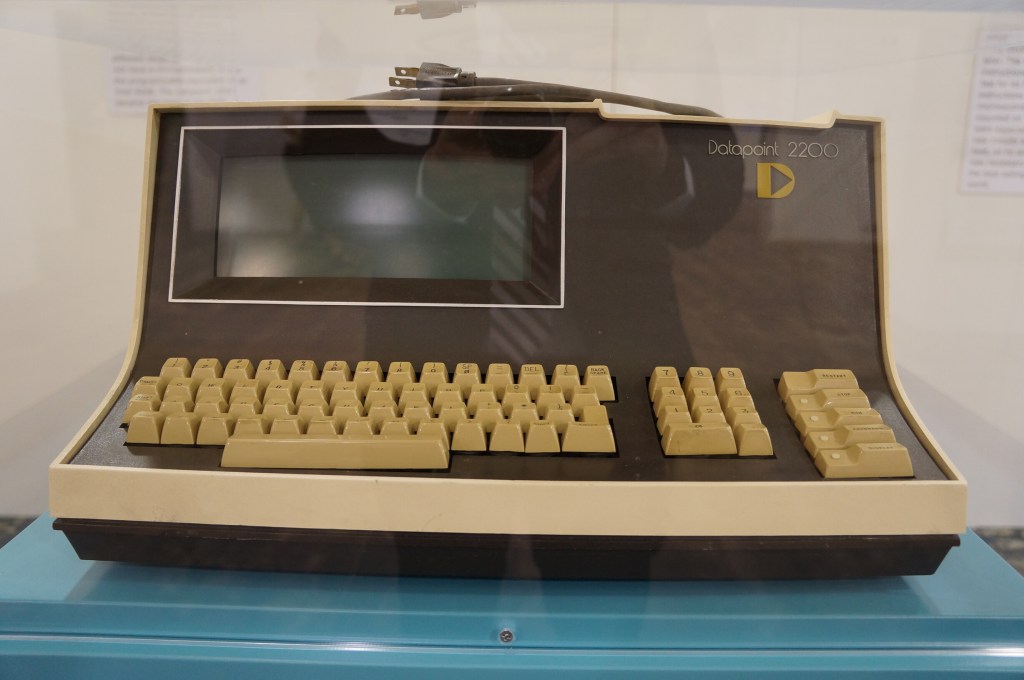

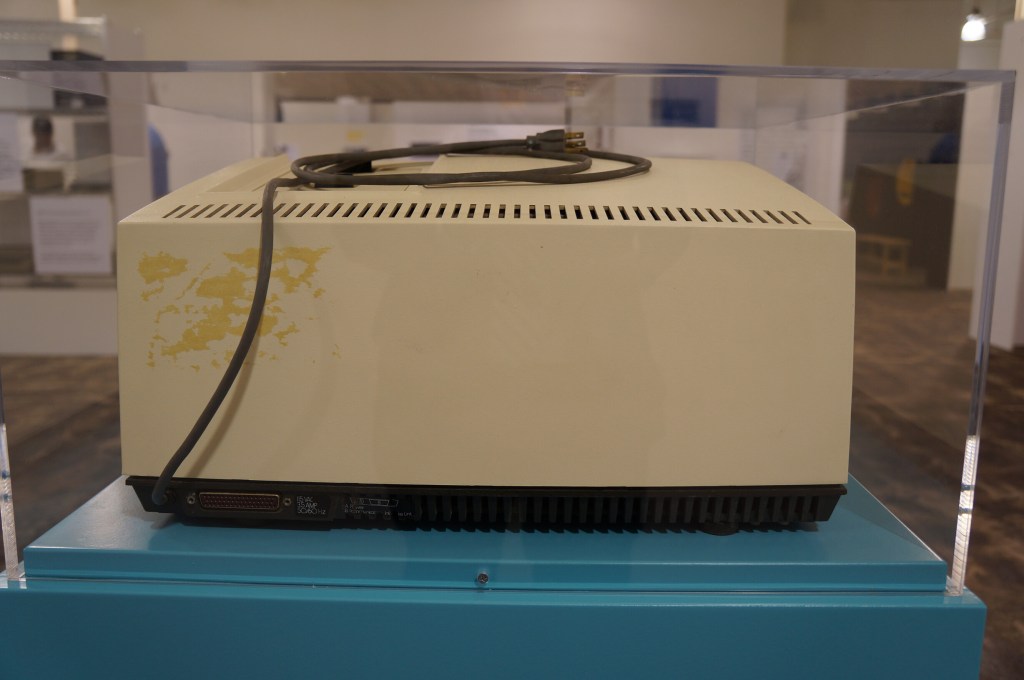

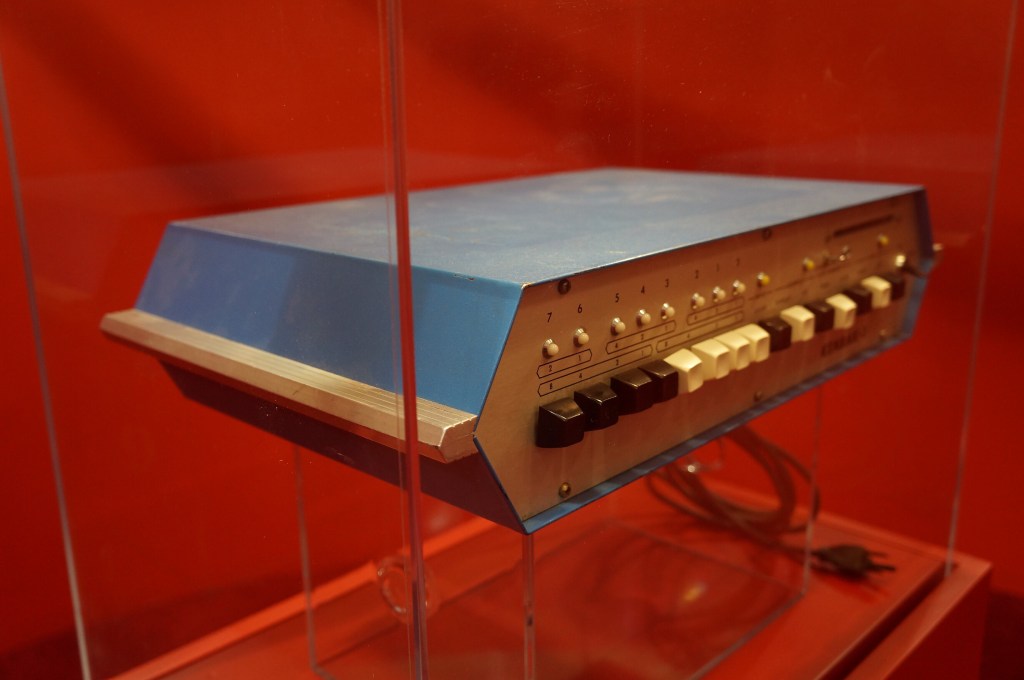

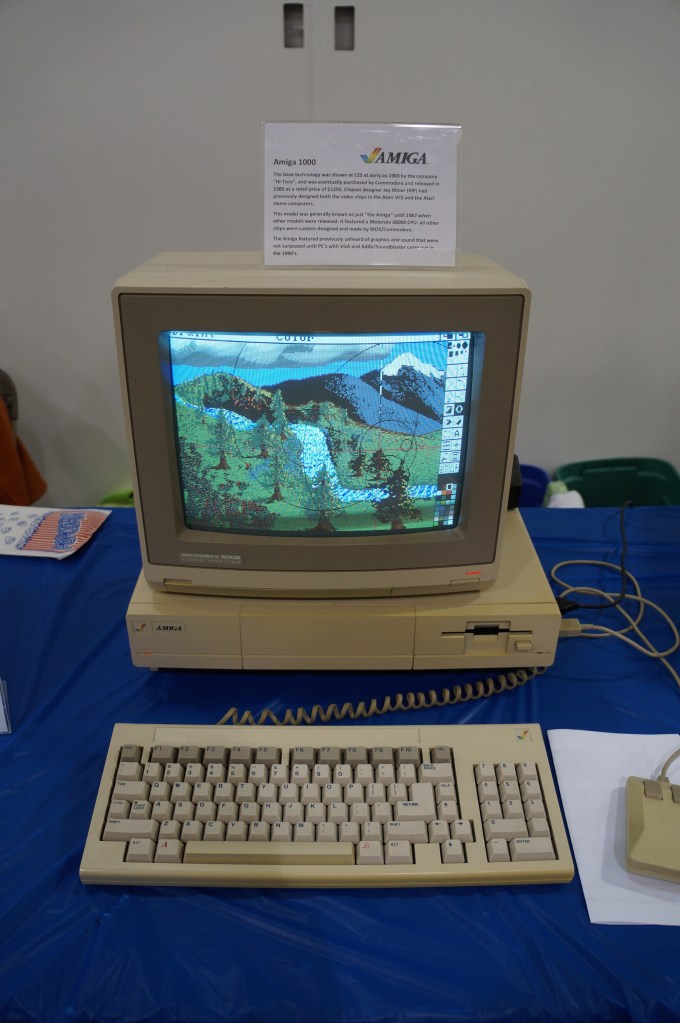

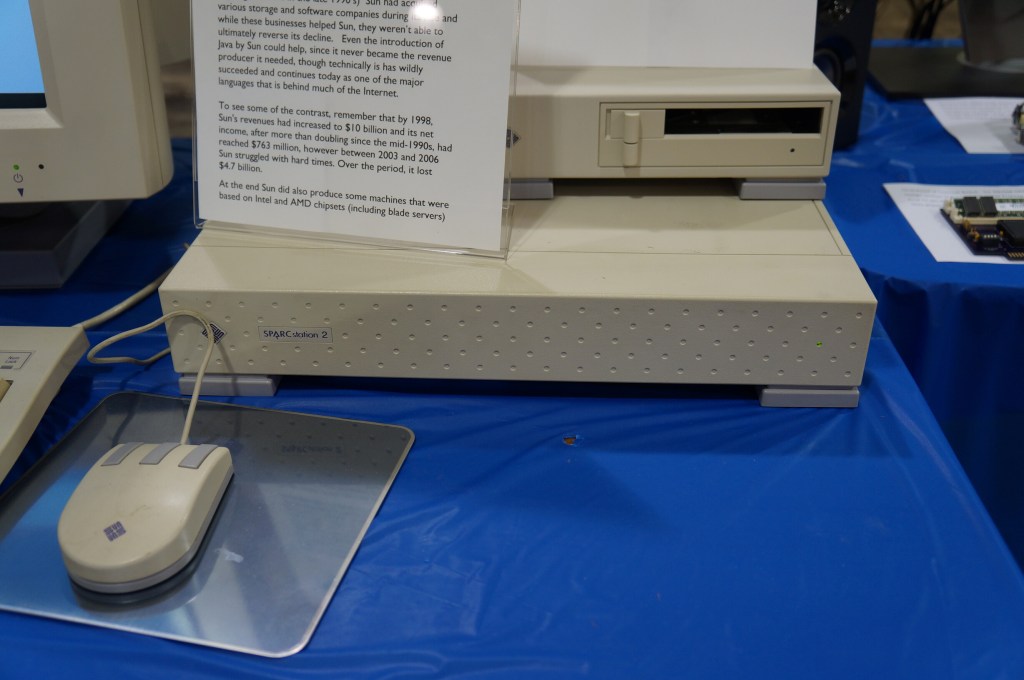

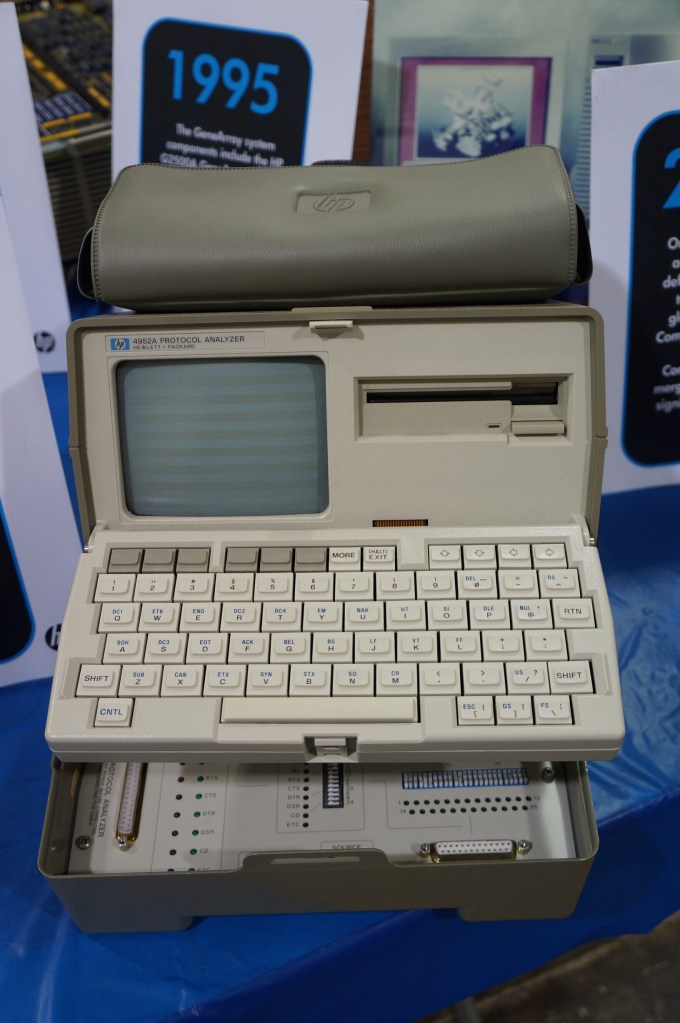

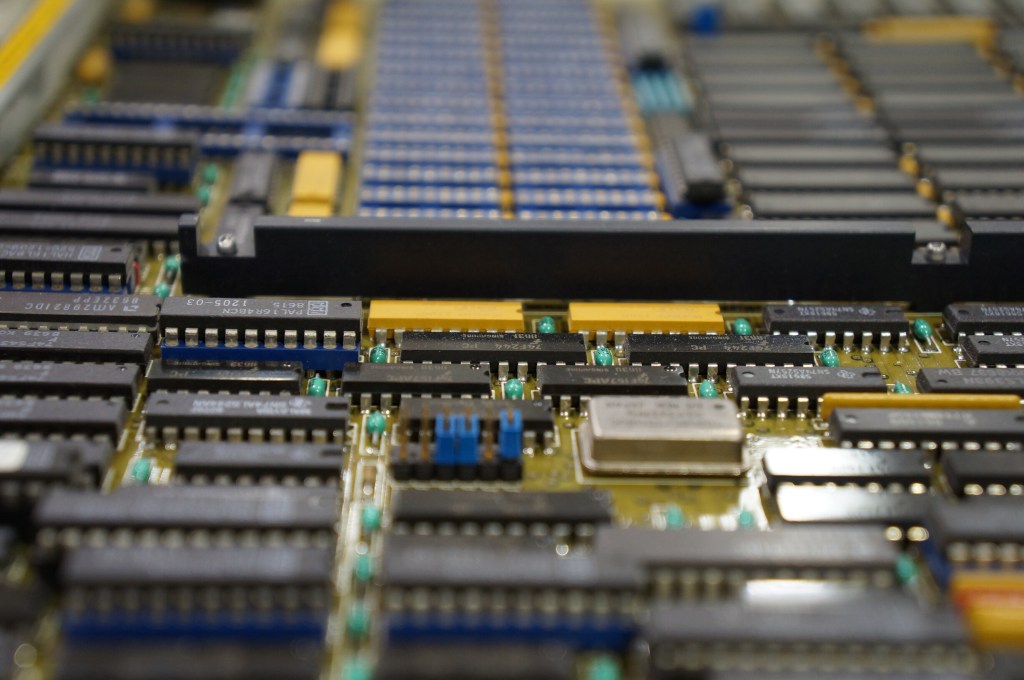

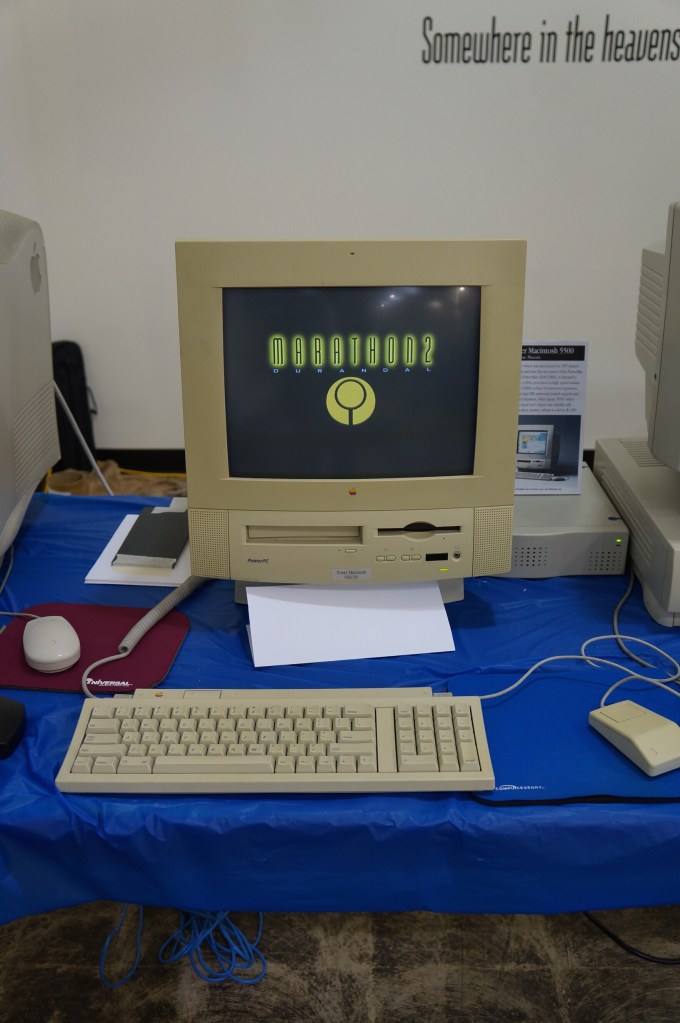

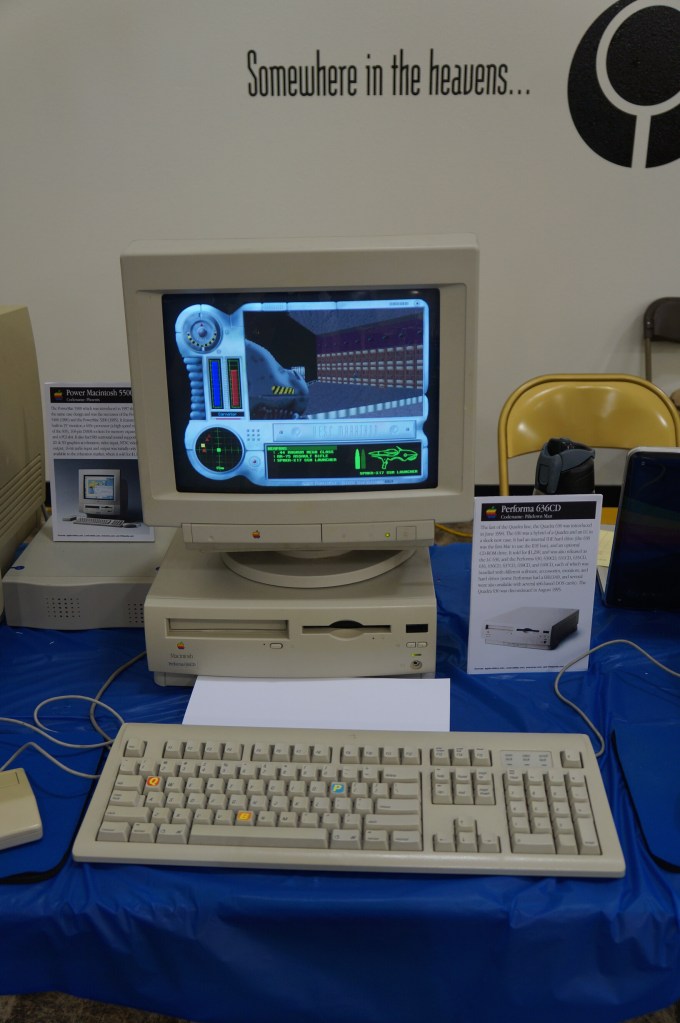

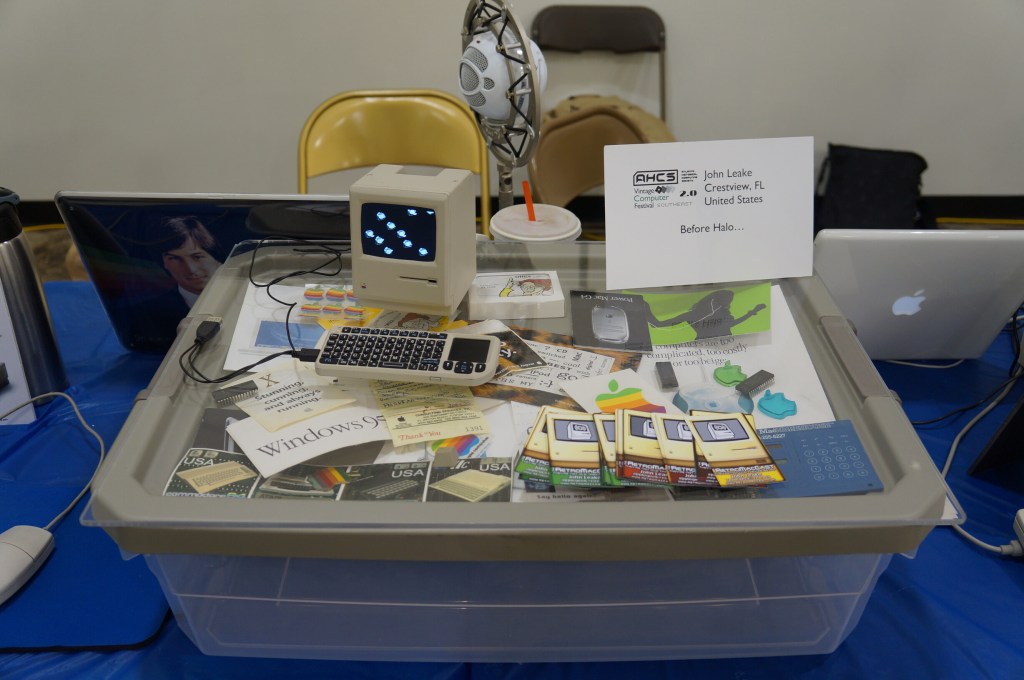

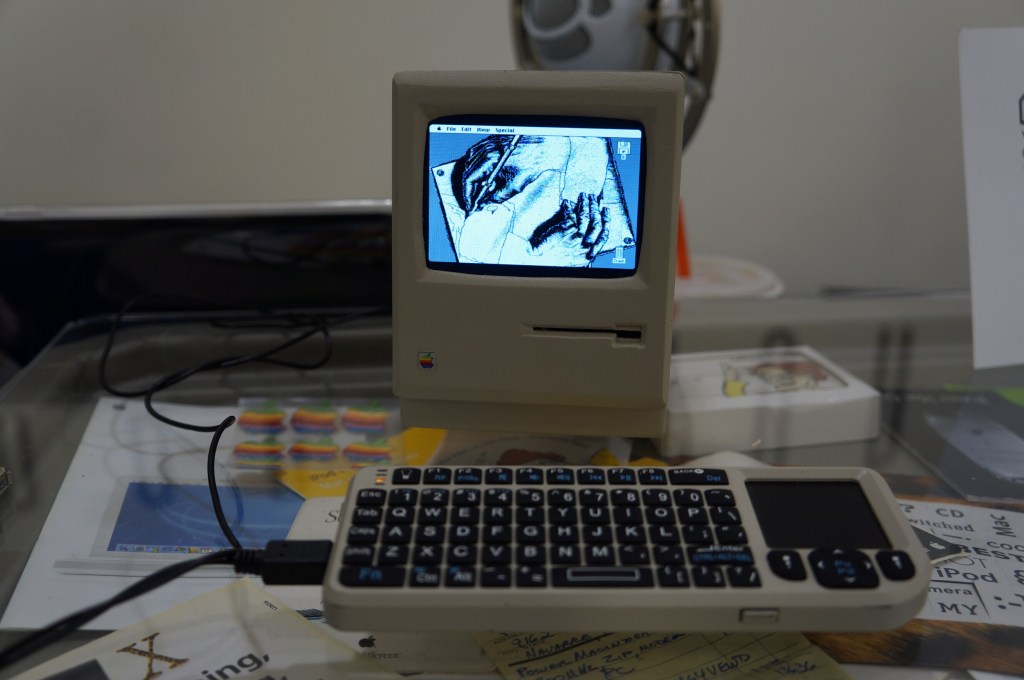

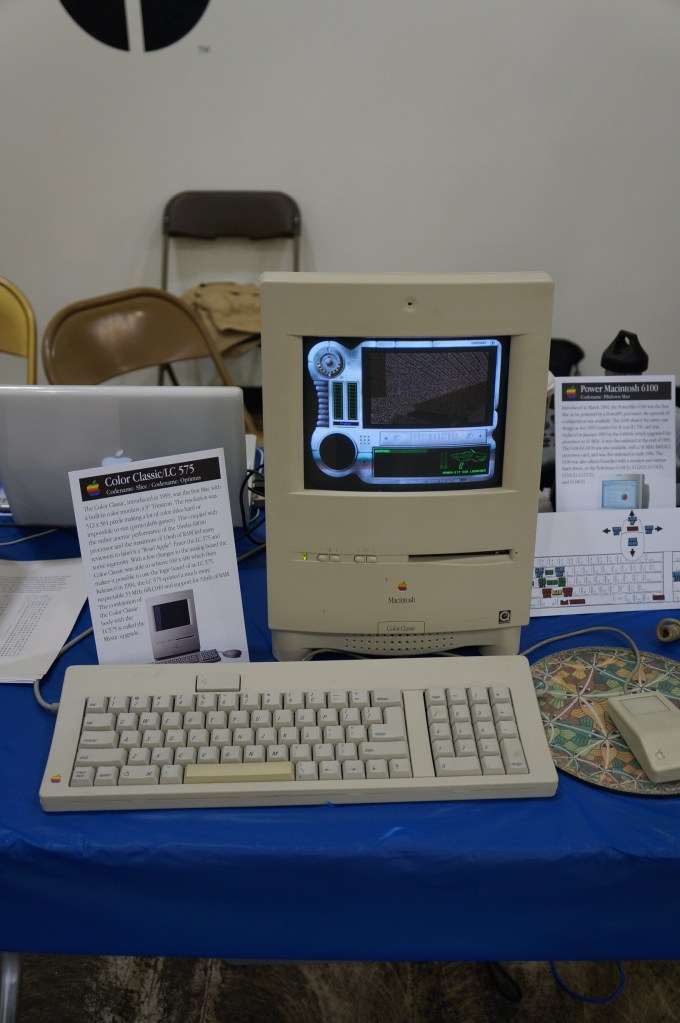

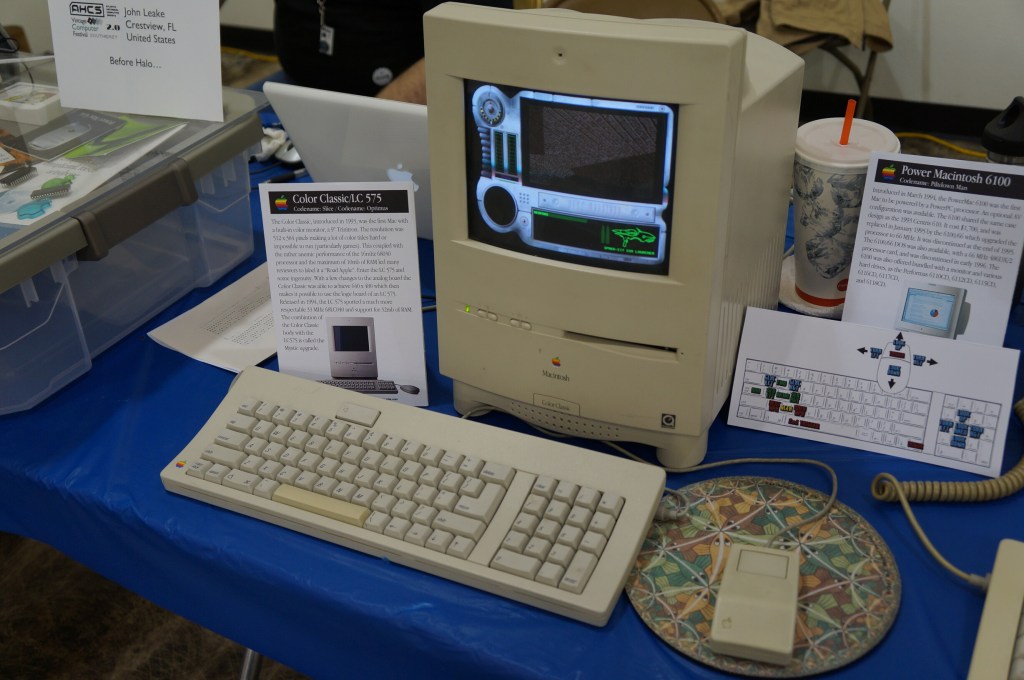

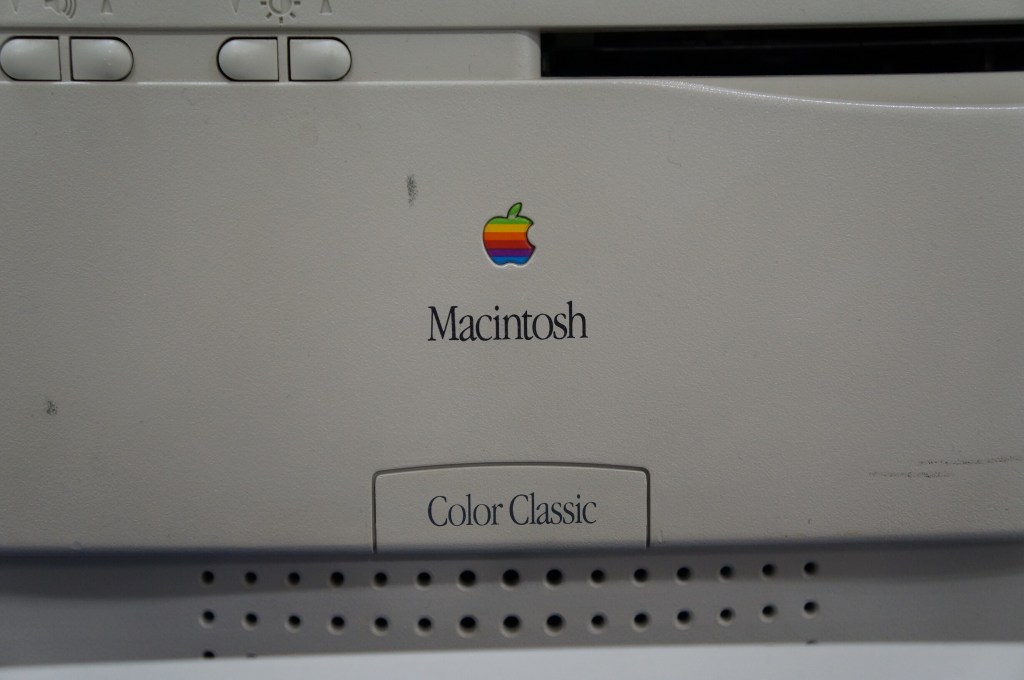

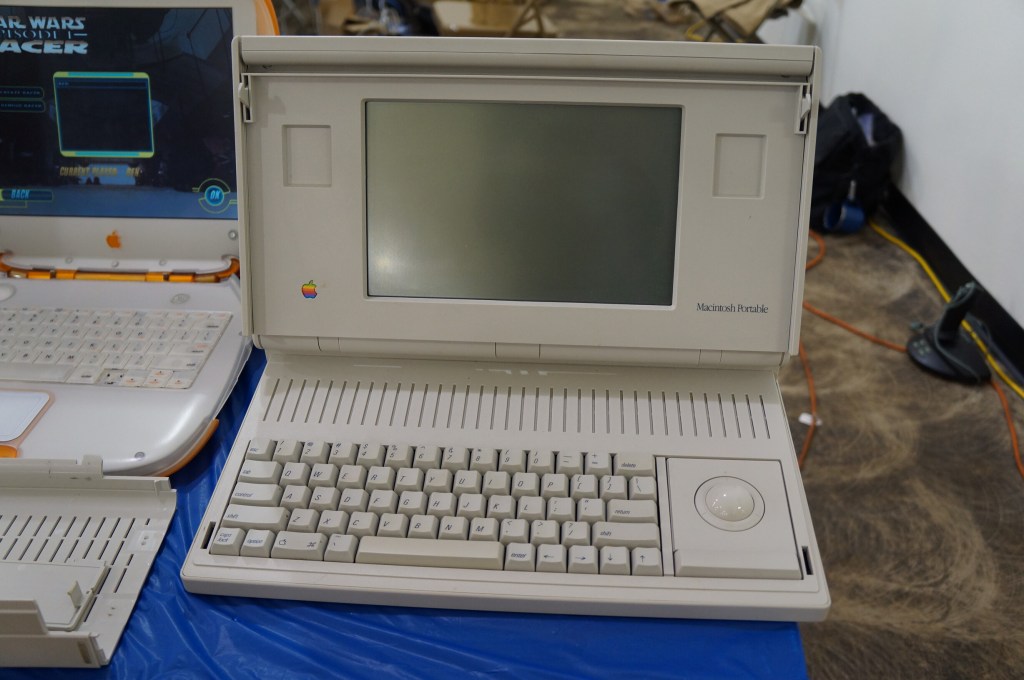

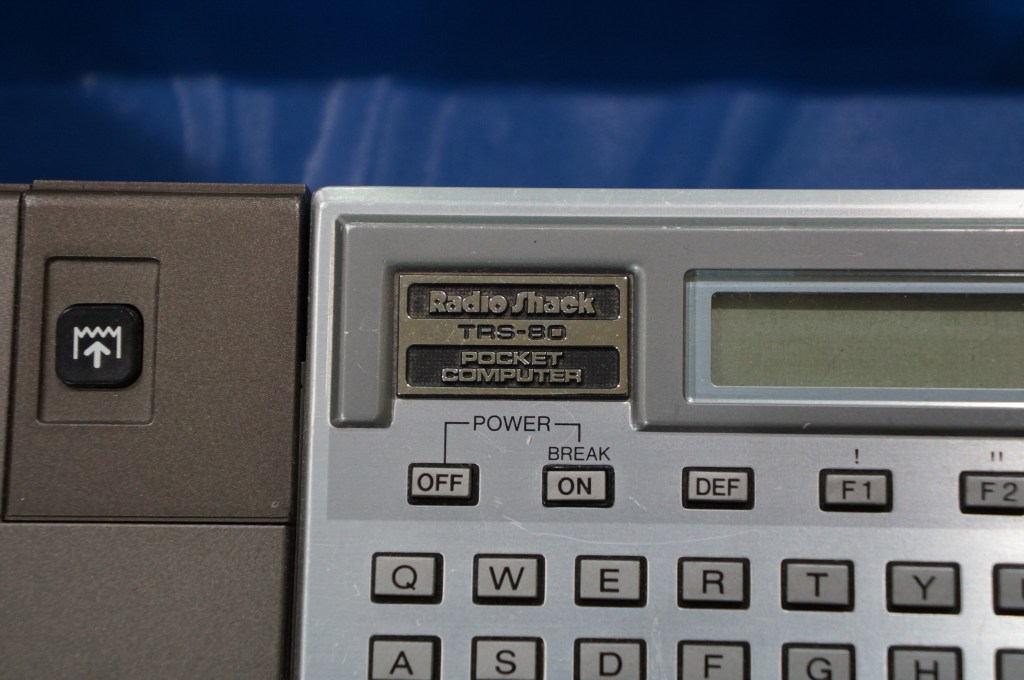

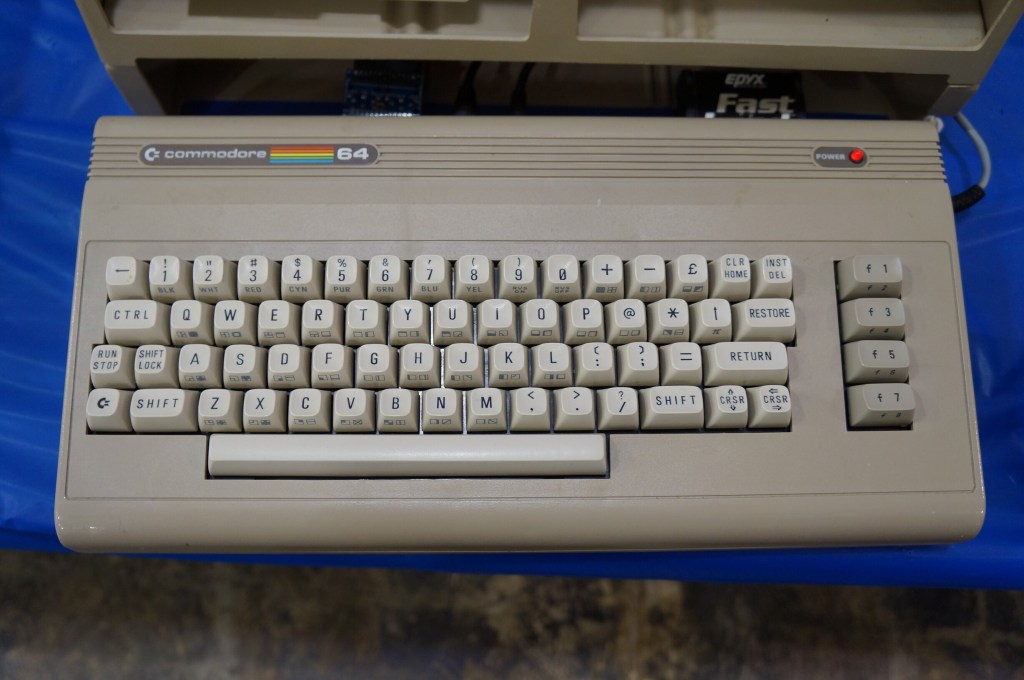

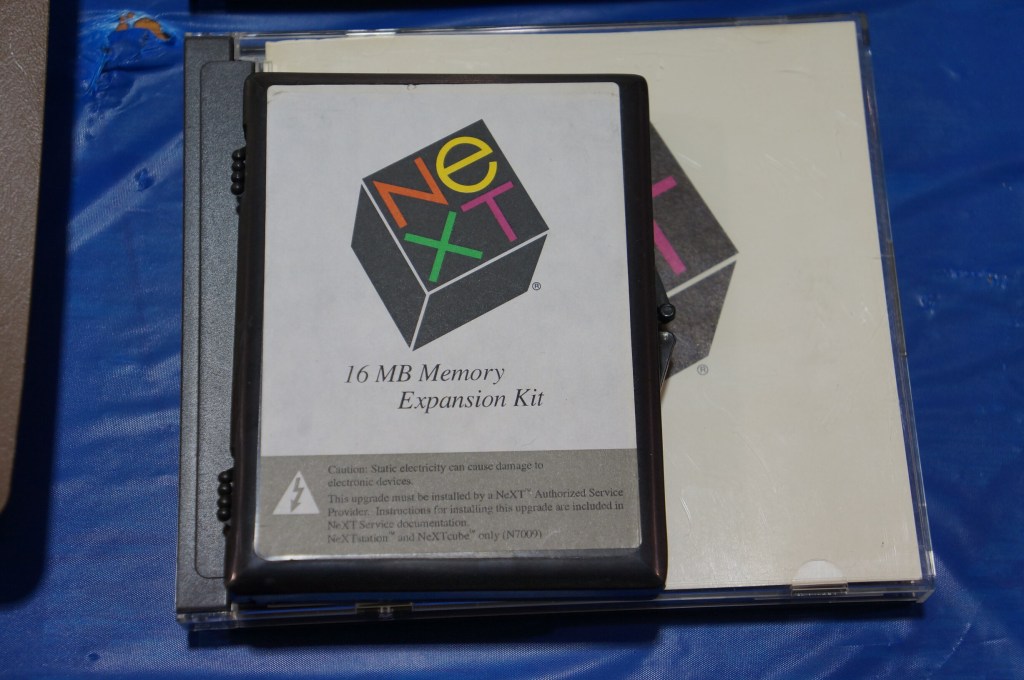

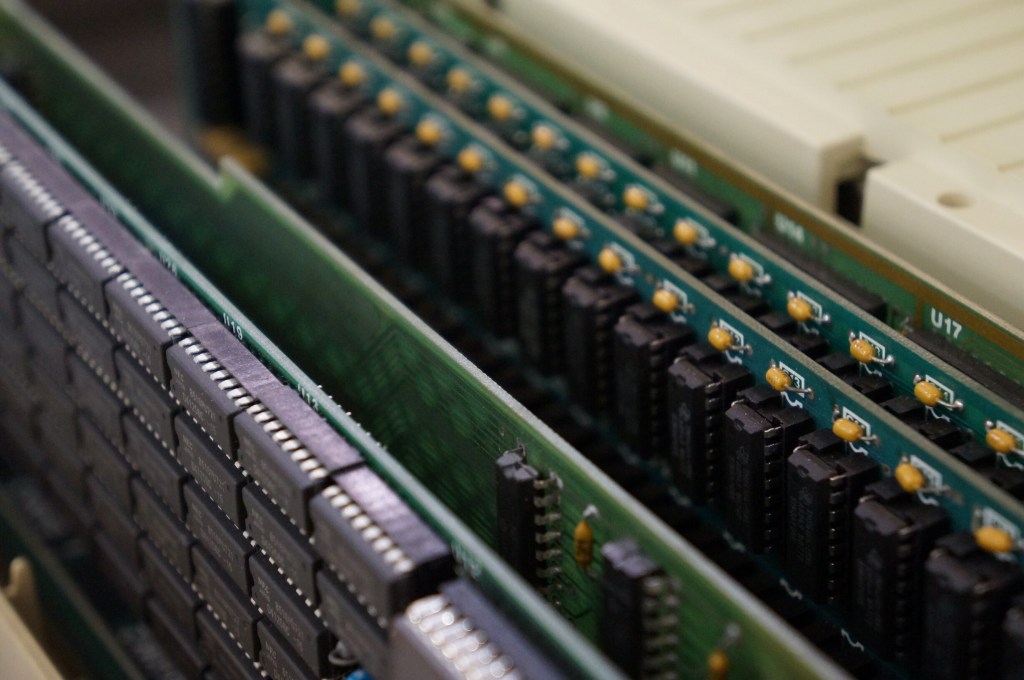

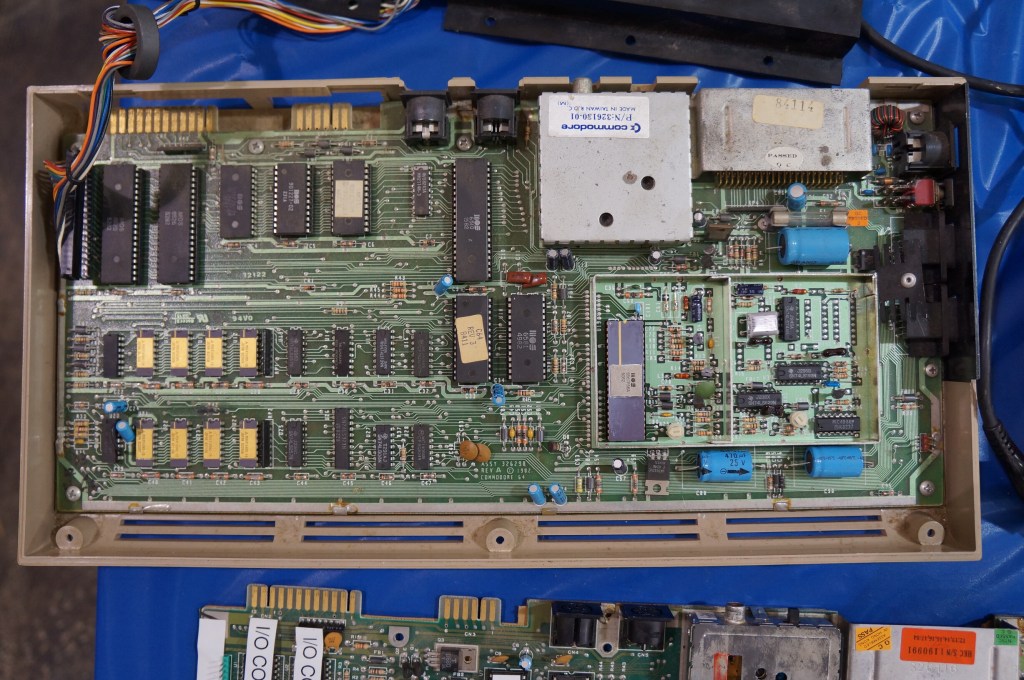

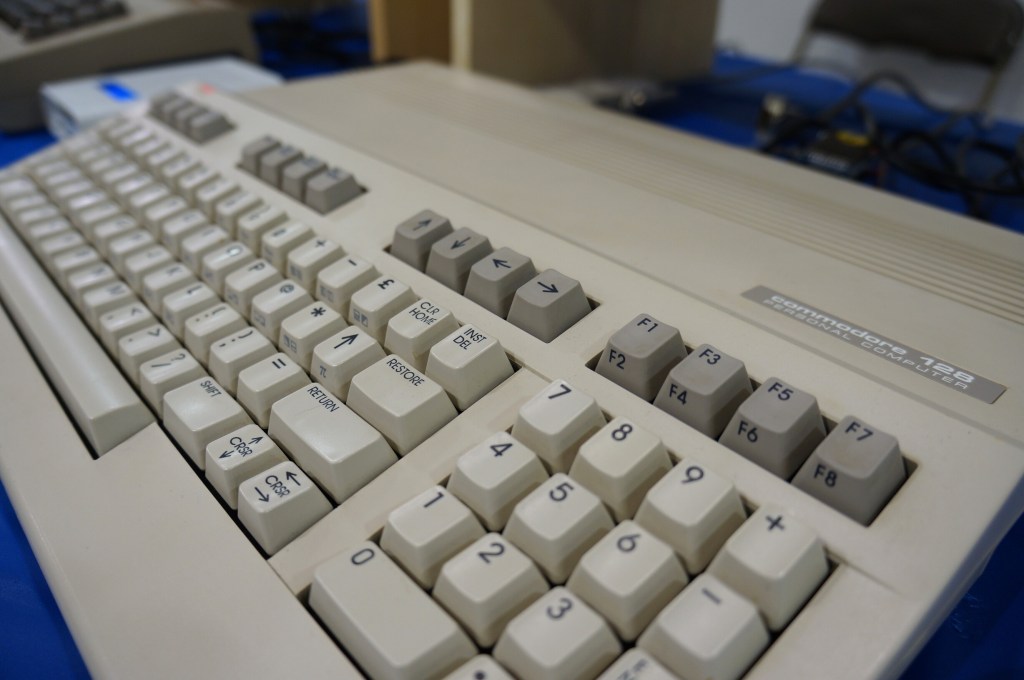

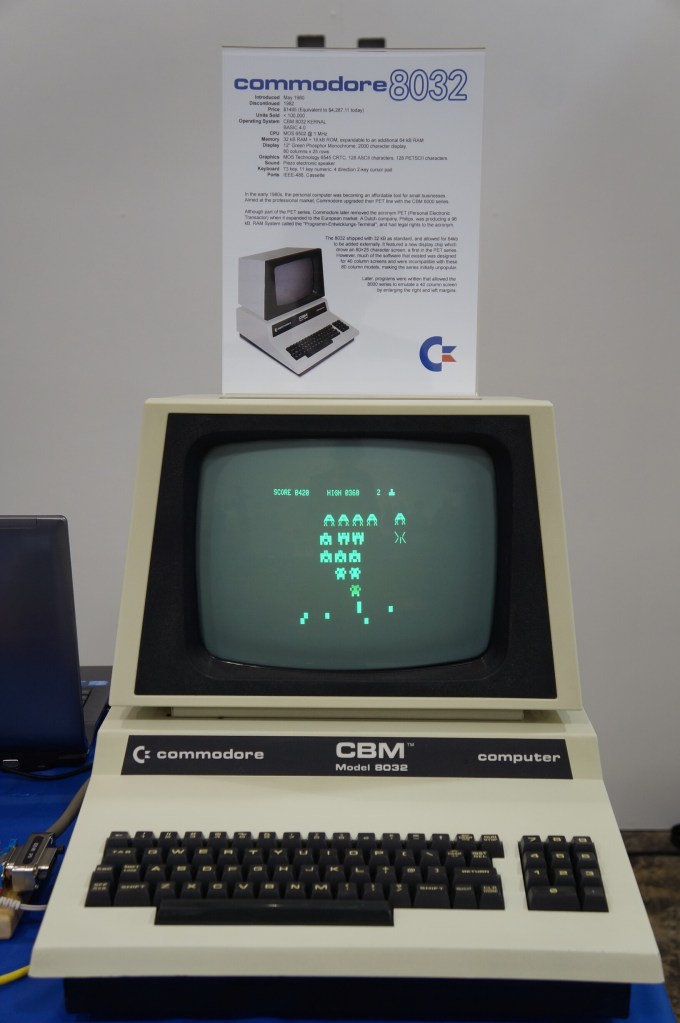

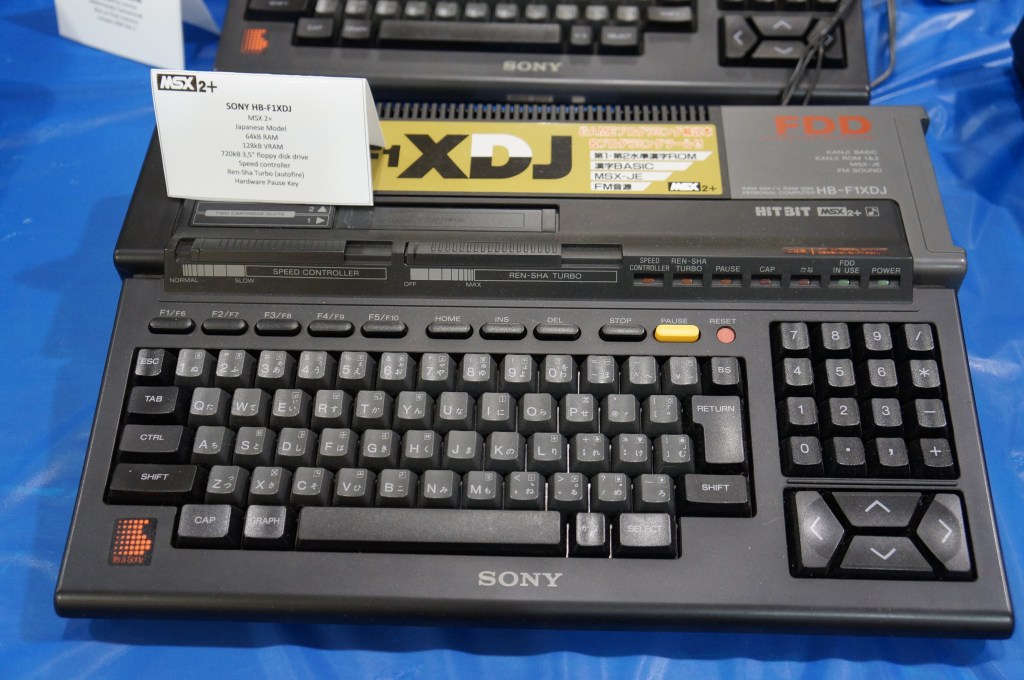

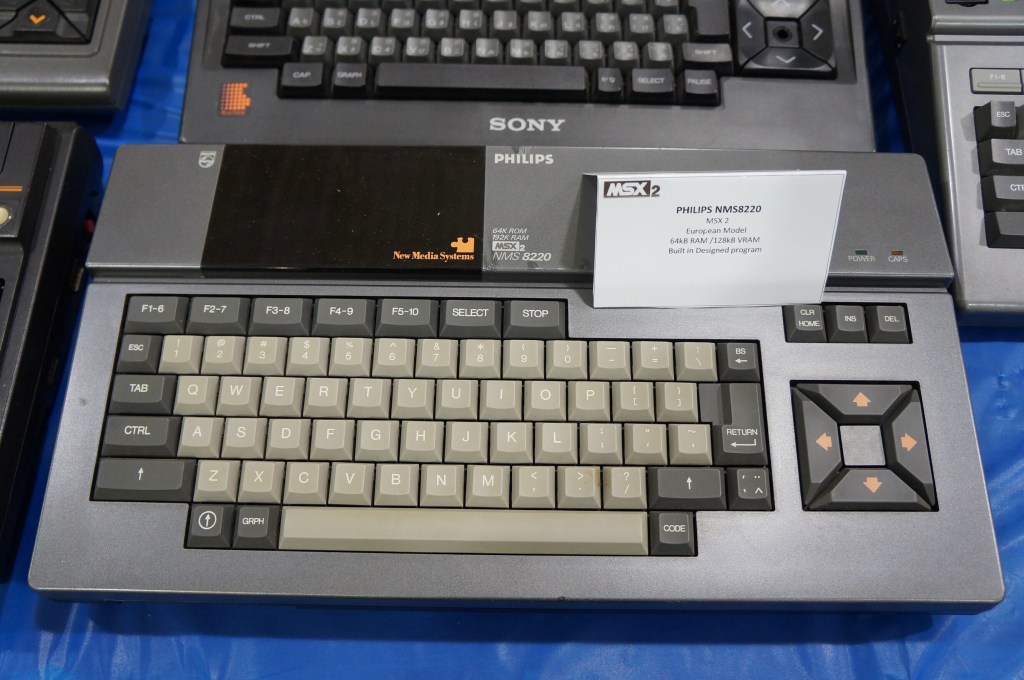

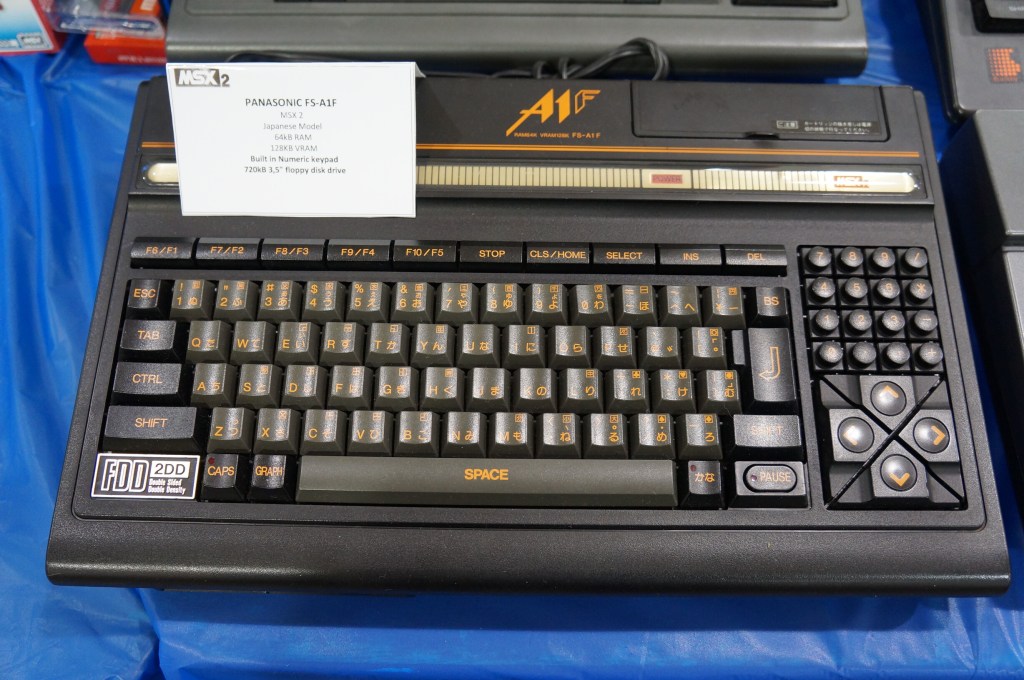

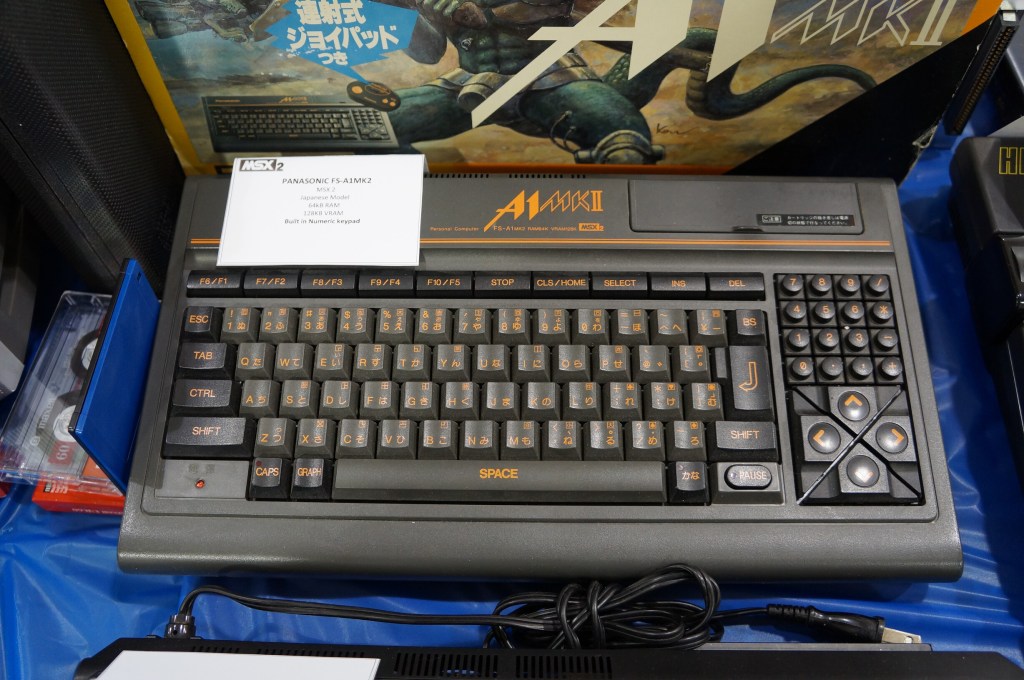

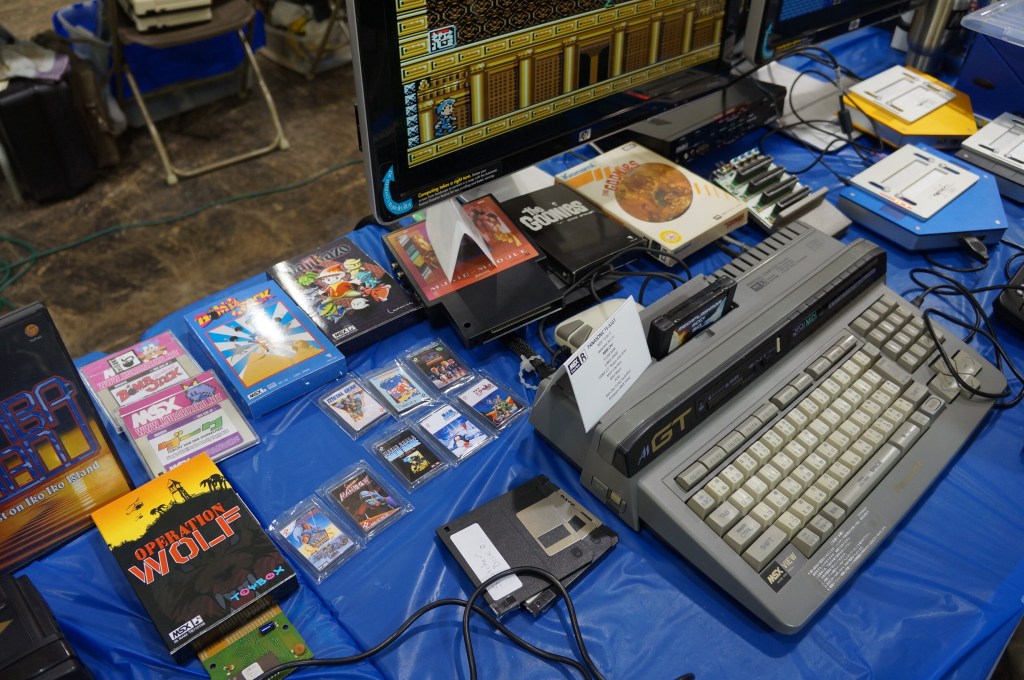

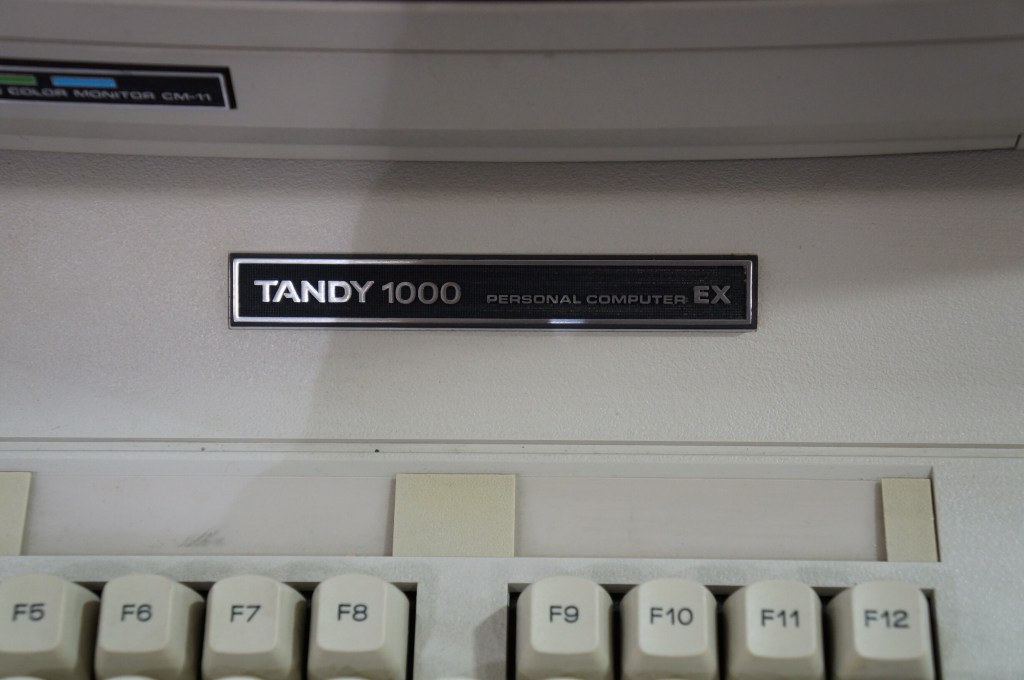

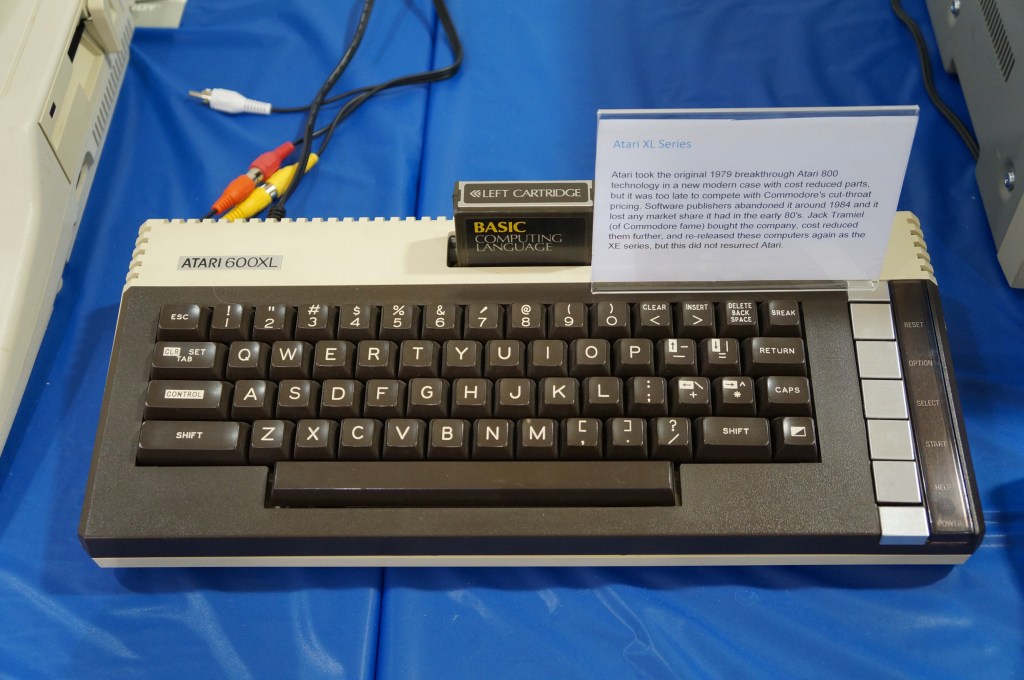

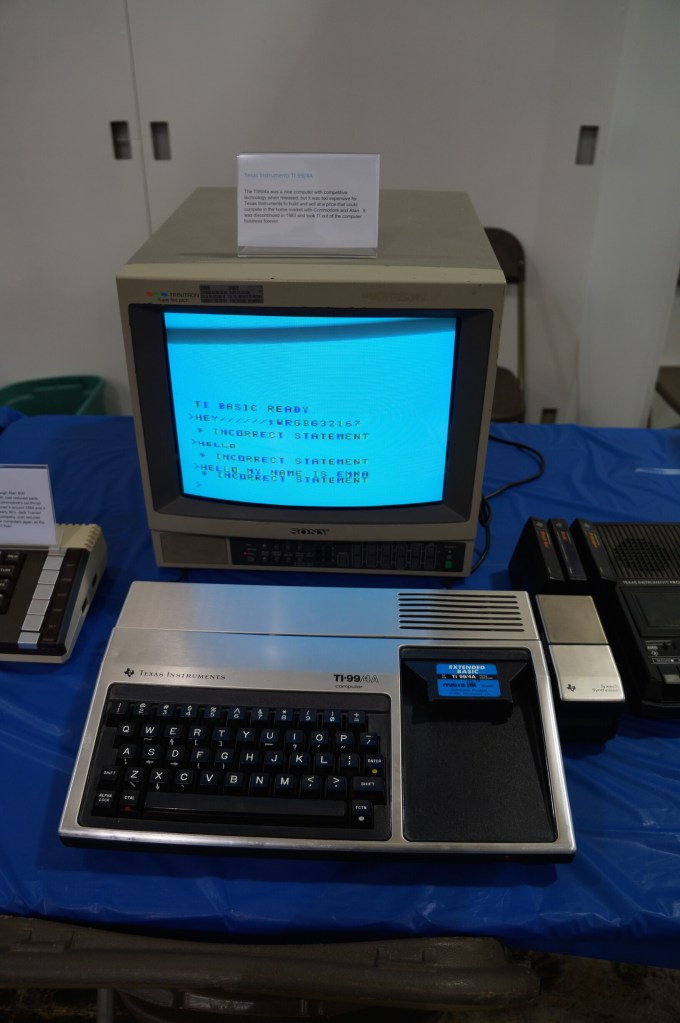

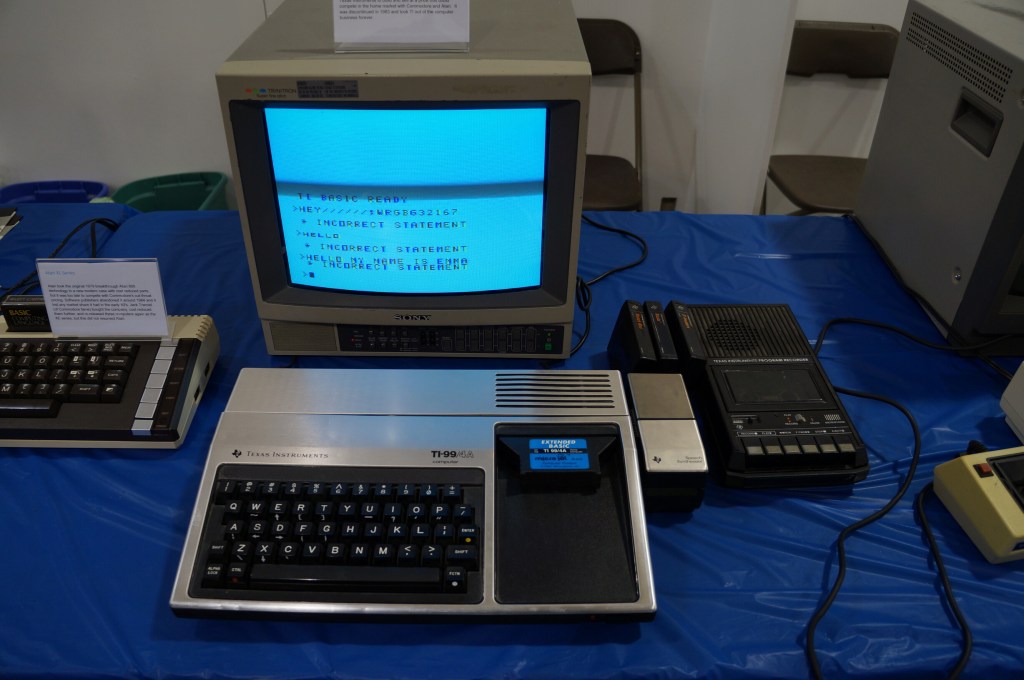

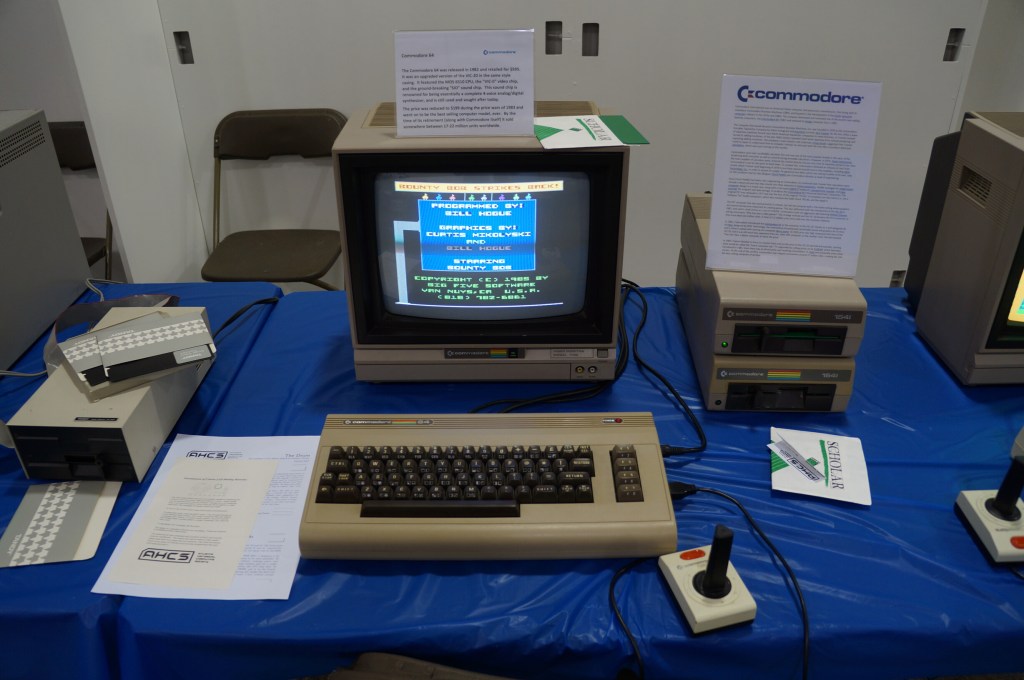

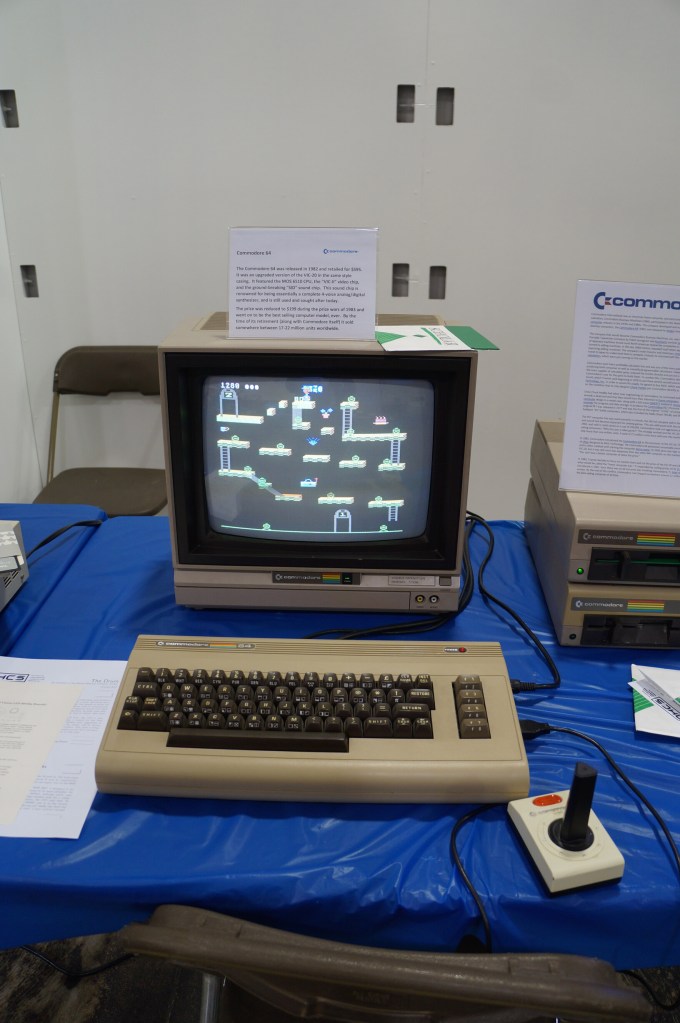

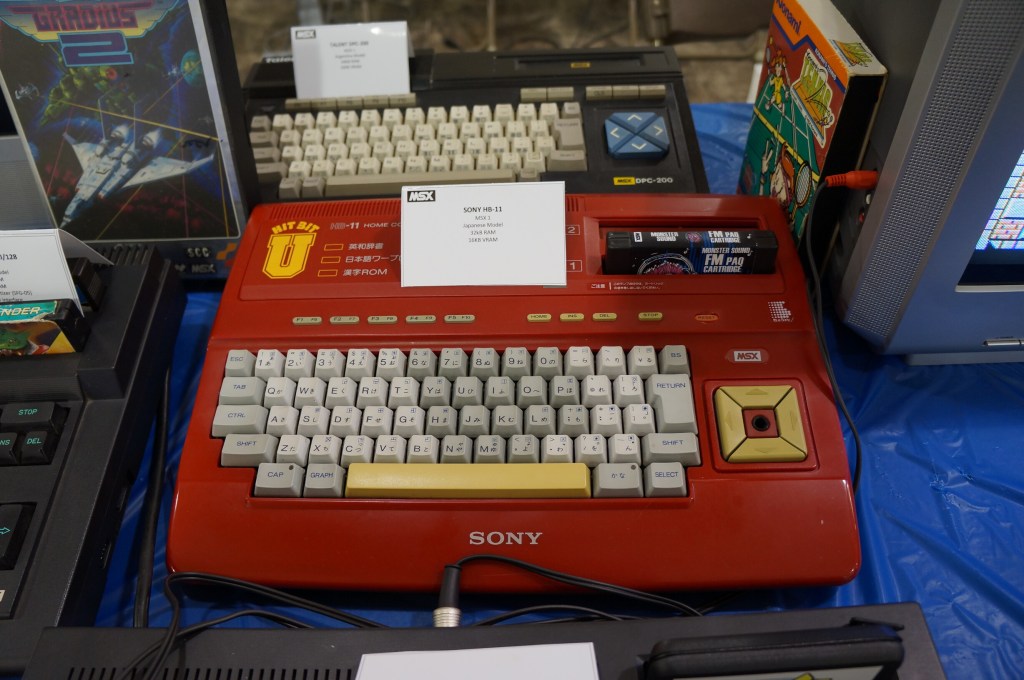

On May 4, 2014 at 11AM, Wendy Hagenmaier and I will give a co-presentation on Digital Archives and Vintage Computing @ Georgia Tech at the Vintage Computing Festival 2.0 in Roswell, Georgia. This post includes a support video embedded below, a link to our PowerPoint presentation, and a transcript of our talk.

On May 4, 2014 at 11AM, Wendy Hagenmaier and I will give a co-presentation on Digital Archives and Vintage Computing @ Georgia Tech at the Vintage Computing Festival 2.0 in Roswell, Georgia. This post includes a support video embedded below, a link to our PowerPoint presentation, and a transcript of our talk.