During last night’s Introduction to Language and Technology (ENG1710) class, I was discussing William Hart-Davidson’s “On Writing, Technical Communication, and Information Technology: The Core Competencies of Technical Communication.” It followed our reading last week of Jacques Derrida’s “Signature Event Context,” which Hart-Davidson engages in part.

Toward the end of lecture, when I was talking about lessons learned from Hart-Davidson’s essay, which includes being a life-long learner and keeping up-to-date on changing technologies of writing and communication, Prof. Sarah Schmerler, a City Tech English department colleague with a shared interest in Generative AI technologies, stopped by and participated in the class discussion with my students. It was informal and impromptu, but I think my students enjoyed their perspective and lived experience. I enjoyed our conversation during and after class.

I wanted to jot down some of the conversation and additional thoughts spun off from the conversation here:

How can you expect to be a good writer without learning, at least in part, from reading many examples of writing by others?

Writing is reading in reverse. Instead of the words coming into you from the world, you are sending the words out into the world.

Reading and writing go hand-in-hand. Developing skill in one, enriches the other.

Reading heuristics, such as lateral reading and vertical reading, can support getting as much as possible out of one’s reading time, energy, and needs (e.g., is this for a research thesis vs. learning enough about something for a journalistic article).

Our needs–enjoyment, learning, work, etc.–play a key role in what strategies (large scale) and tactics (smaller scale) we employ to accomplish reading goals.

Reading can be a passive exercise, but active reading that engages the text and combines cognition, reasoning, and imagination yields the greatest returns in terms of understanding, analysis, and memory.

Isolation, quiet contemplation, and dedicated time can aid the development of reading and writing.

Teaching writing requires a rethink on how we approach reading and how important reading is to developing writing skill.

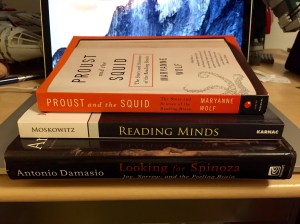

Ray Bradbury was a largely self-educated writer who proudly said that he graduated from the library at the age of twenty eight (though, he adjusted this to twenty seven in a later interview in the Paris Review). In the latter interview, he also remarked about retyping the writing of his favorite authors as a part of his writing apprenticeship and early development as a writer–“[to] Learn their rhythm.”

Students do lots of different kinds of reading, which we as educators can tap into and help the student connect their reading interests to writing development. Furthermore, it can open doors to other kinds of reading that they were not previously aware of. Knowing where they are and interested can lead to possibilities and knowledge that were around them but unseen. Browsing and finding the neighborhood, in Prof. Schmerler’s terms, connects students to new reading opportunities.