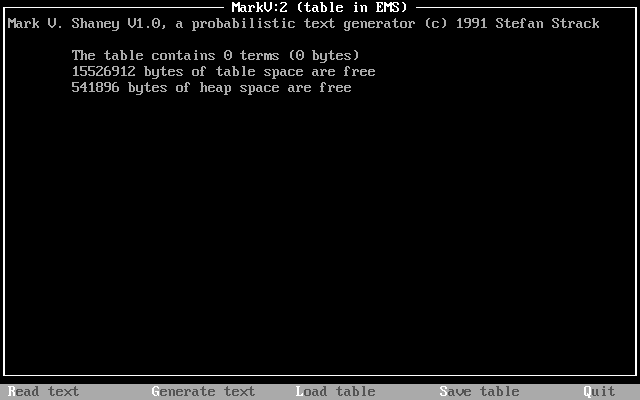

Of the text generators that I’ve discussed this past year, Mark V. Shaney v. 1.0 (MARKV.EXE) is by far the simplest to use but it is also one of the most advanced due to its implementation of weighted probability tables (Markov chains–the program’s name is a pun on this) that underpin how it generates text. I was able to obtain a copy from the TextWorx Toolshed archived on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

MARKV.EXE (44,365 bytes) was developed in 1991 by Stefan Strack, who is now a Professor of Neuroscience and Pharmacology at the University of Iowa. In the MARKV.DOC (10,166 bytes) file that accompanied the executable, Strack writes, “Mark V. Shaney featured in the “Computer Recreations” column by A.K.Dewdney in Scientific American. The original program (for a main-frame, I believe) was written by Bruce Ellis based on an idea by Don P. Mitchell. Dewdney tells the amusing story of a riot on net.singles when Mark V. Shaney’s ramblings were unleashed” (par. 2). Dewdney’s article on the MARKV.EXE program appears in the June 1989 issue of Scientific American. The article that Strack mentions is available in the Internet Archive here. A followup with reader responses, including a reader’s experiment with rewriting Dewdney’s June 1989 article with MARKV.EXE, is in the January 1990 issue here.

The program works by the user feeding a text into MARKV.EXE, which is “read.” This generates a hashed table of probabilistic weights for the words in the original text, which can be saved. The program then uses that table and an initial numerical seed value to generate text until it encounters the last word in the input text or the user presses Escape. The larger the text (given memory availability) , the more interesting its output text, because more data allows it to generate better probability weights for word associations (i.e., what word has a higher chance to follow a given word). Full details about how the program works can be found in the highly detailed and well-organized MARKV.DOC file included with the executable.

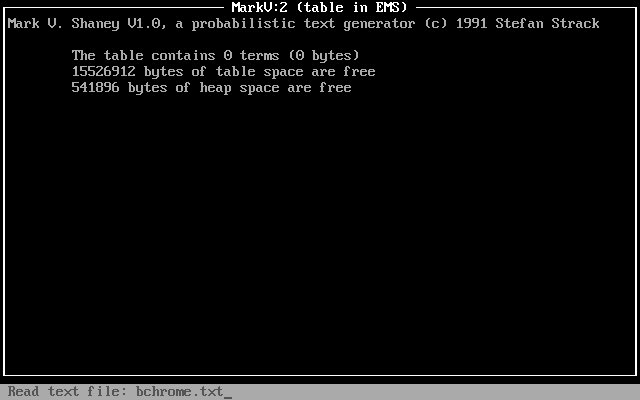

Using DOSBox on Debian 12 Bookworm, I experimented by having MARKV.EXE read William Gibson’s “Burning Chrome” (1982). I pressed “R” for “Read,” entered the name of the text file (bchrome.txt), and pressed enter.

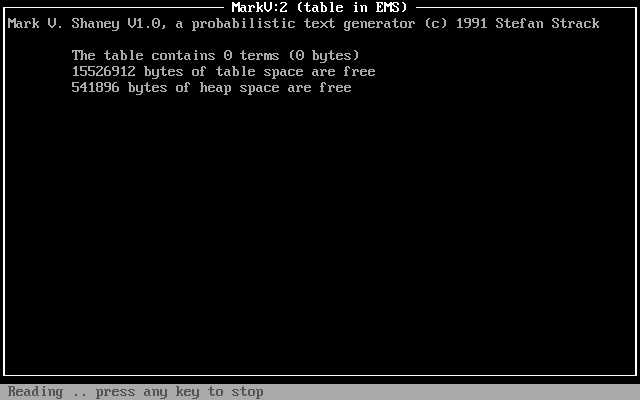

The program reported “reading” for a few minutes (running DOSBox at default settings).

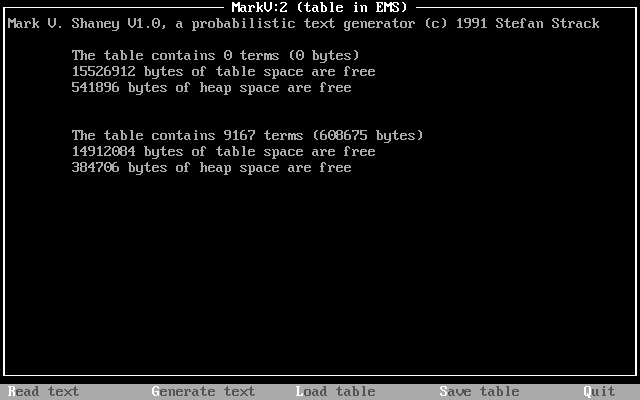

After completing its “reading,” the program reported stats on the table that it created using bchrome.txt: 9167 terms (608,675 bytes).

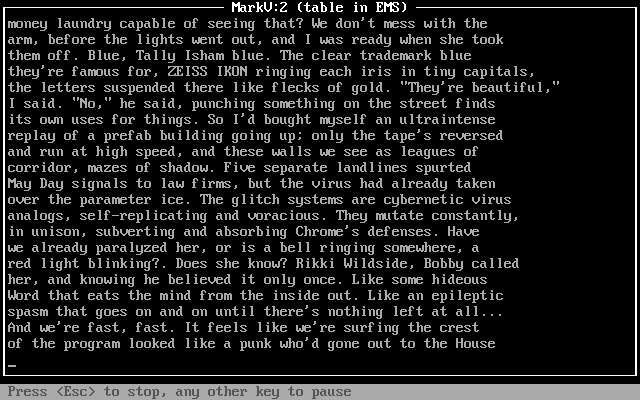

I pressed “G” and the program began to generate text based on its table of probabilities generated from the bchrome.txt text file, which contained the short story, “Burning Chrome.” While the generated text flows across the screen, there are options to press “Esc” to stop or any other key to pause.

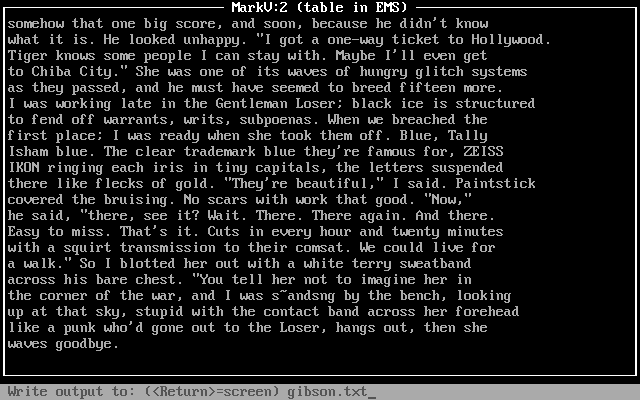

After it completed writing the generated text to the screen, I pressed “S” to save the generated text and it prompted me to type in a file name for the saved generated text: gibson.txt.

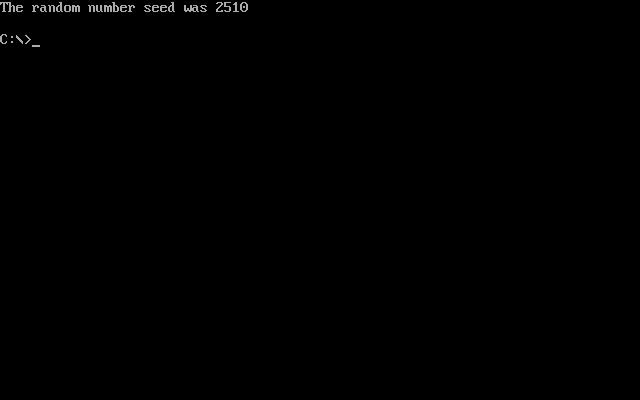

Pressing “S” gives the user an option to save the table for future use. I went with the default name, MARKKOV.MKV (not to be confused with a modern Matroska container file). This file can be loaded in MARKV.EXE on subsequent runs by pressing “L” and entering the name of the table. When the user presses “Q”, the program exits back to DOS and displays a message, “The random number seed was x,” where x is a random number used in the generation of text. If repeatability is important to the user, you’ll want to make a note of that number and use it with the -s modifier when running MARKV.EXE again (e.g., markv.exe -s2510).

Mark V. Shaney’s implementation of a Markov chain that builds a table of next word probability on a small text sample is one example of the predecessors to large language models (LLMs) like LLaMA and ChatGPT. However, Mark V. Shaney’s word association probabilities is far simpler than the much more complicated neural networks of LLMs (especially considering attention) with many orders of magnitude more parameters trained on gargantuan data sets. Nevertheless, Mark V. Shaney is one aspect of the bigger picture of artificial intelligence and machine learning development that led to where we are now.