I’ve wanted an IBM ThinkPad since I first saw my boss’ at Netlink in the fall of 1998. But, while I’ve been invested in PCs over the years tangentially, I reserved Macs as my primary desktop or laptop computing platform, which combined with the premium price on IBM and then Lenovo ThinkPads kept me in the Apple premium category. Put another way, I could afford one but not both.

Apple, as I’ve confided with friends, is diverging from my computing interests and needs. While design has been an important part of Apple’s DNA since the Apple II (arguably even earlier if we consider Woz’s design aesthetics for the Apple I motherboard layout), its increasing emphasis on fashion and accessorization and seeming less technological investment and innovation in its desktop and laptop computers have soured my allegiance to the company and its computers.

So, I thought about how to try out a different kind of PC laptop–one that I had wanted but could not afford when it was originally released–and make an investment in extending the life of what some folks might consider an obsolete or recyclable computer.

Within this framework, I wanted a laptop to take the place of the MacBook Pro that I had sold on eBay awhile back while the resell value was still high before rumored price reductions as product refreshes roll in. It needed to be relatively lightweight and have a small footprint. Also, it needed to have good battery life. And of course, it needed to run the software that I use on my home-built desktop PC.

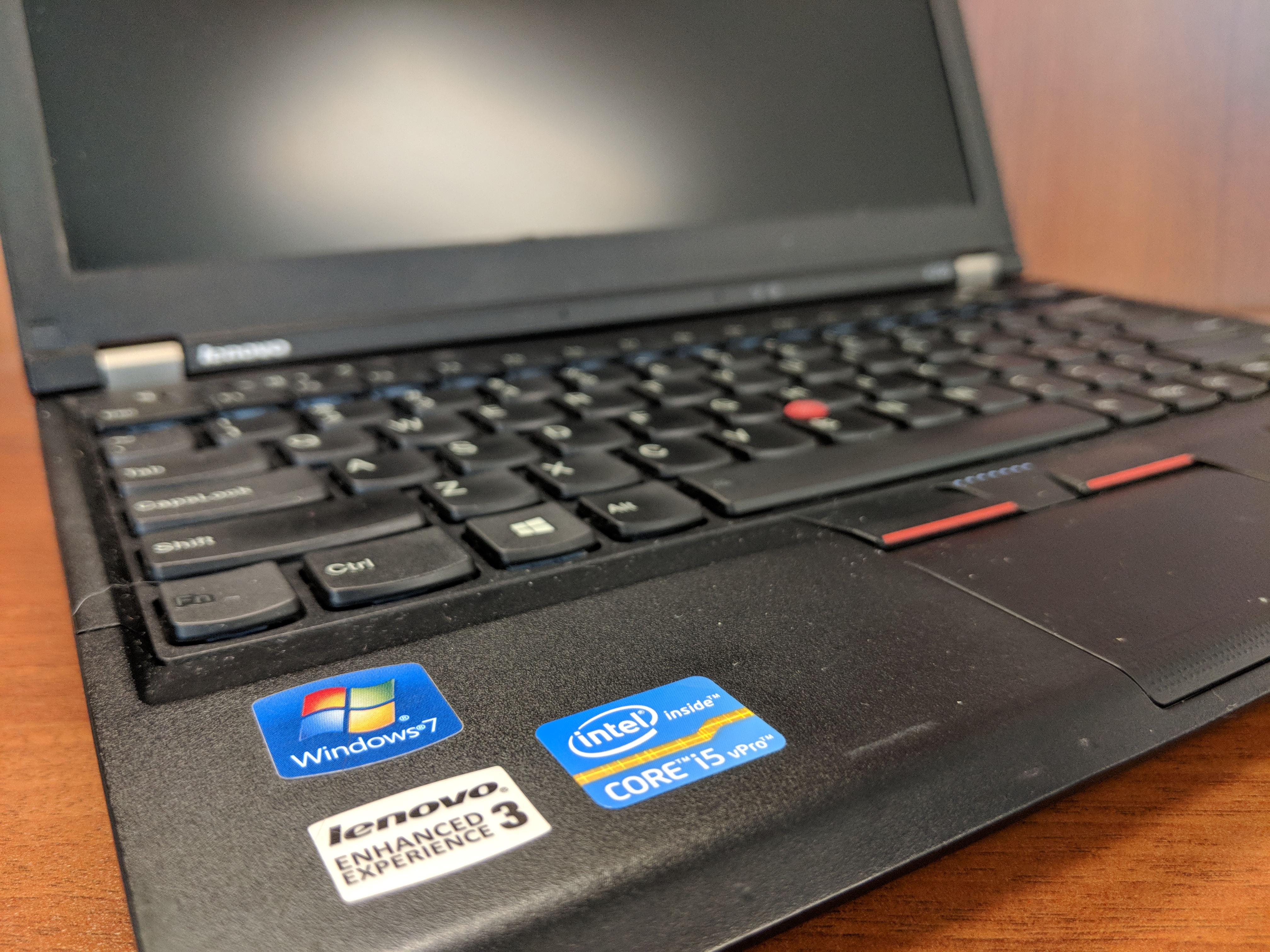

Eventually, I decided to purchase a very well taken care of Lenovo ThinkPad X230 on eBay. Originally released in 2012 for a lot more than what I paid for it, this ThinkPad model features an Intel Core i5 3320M Ivy Bridge CPU running at 2.6GHz with 2 cores and supporting 4 threads. It has 8GB DDR3 RAM and a 180 GB SSD. In addition to built-in WiFi, it has an ethernet port, 3 USB 3.0 connectors, an SD Card reader, VGA and Display port connectors, and a removable battery.

From a user interface perspective, it has a chiclet keyboard which responds well to typing quickly. Its touchpad leaves a little to be desired in terms of responding to some gestures like scrolling, but its red pointing nub and paddle-style mouse buttons at the top of the touchpad are exquisite. It includes some feature buttons like a speaker mute button next to volume keys above the function key row, and on the left side there is a radio on/off switch for the WiFi and Bluetooth.

Initially, I tried out the ThinkPad X230 with Ubuntu, and everything seemed to work out of the box (though, I added TLP for advanced power management). However, I switched back to Windows 10 Professional with a full nuke-and-pave installation, because I have some software that is far easier to run natively in Windows instead of through Wine or virtualization in Linux.

In Windows 10 Professional, the ThinkPad X230 meets all of my productivity needs. I use LibreOffice for most things, but I also rely on Google Docs in Chrome for some tasks (like inventorying the City Tech Science Fiction Collection). The WiFi works well even at City Tech, which has one of the most cantankerous wireless networks I’ve encountered. At home, I use it on my lap to browse while watching TV.

The X230 is snappy and quick despite its age. Of course, the SSD and ample RAM support increased input/output for the older CPU. Chrome, LibreOffice, and Windows Explorer respond without hesitation. It easily plays downloaded Solo: A Star Wars Story 1080p trailers in VLC, too.

With the included 6 cell 45N1022 battery, it runs for several hours (this is a used battery, so its capacity might be lower than one that is brand new). I purchased a 9 cell 45N1175 battery, which I’m testing out now. With the 6 cell battery, it is just shy of 3 pounds, and with the 9 cell battery is a little over 3 pounds. I’m hoping that between the two of them that I can get plenty of work done on the go without being tethered to a power outlet.

Future tests include running World of Warcraft and watching full length movies. The display’s viewing angles could be better, but I’m willing to accept them as they are as I can adjust the brightness and display gamma easily using keyboard shortcuts and the Intel Display Adapter software to minimize its poorer display quality as compared to the latest HiDPI displays available now.

I’m tickled to use the Lenovo ThinkPad X230 as my main laptop. Now, I can say that I’m a proud ThinkPad owner instead of a zealous Apple user.

At the bottom of this post, I’ve included more photos of the X230.

If you’re considering a new computer, I would, based on this and my other vintage computing experiences, suggest that you consider trading up for a used or refurbished machine. Getting a used computer keeps that computer out of a landfill or being destroyed for its rare metals, and it might be an opportunity to try out a computer that you might have missed on its first time around.