Continuing my exploration of non-artificial intelligence (non-AI) programs that can generate images (see KPT Bryce and Evolvotron) and text (see Electric Poet 1.6), I discovered this really innovative piece of text generating software by Mark Pilgrim called Kant Generator Pro 1.3.1 for Macintosh 68k computers.

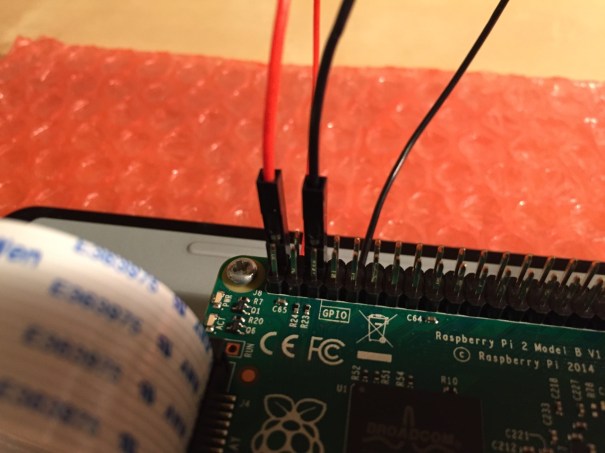

The Kant Generator Pro folder, which includes the Kant Generator Pro application, Program Notes file, and folders for its text generating modules and scripting, is only 560K. The Kant Generator Pro application is 176K and it has a suggested RAM size of 1,024K. The copy that I downloaded from Macintosh Garden here had the minimum RAM size set at 512K and the Preferred size set to 11,024K.

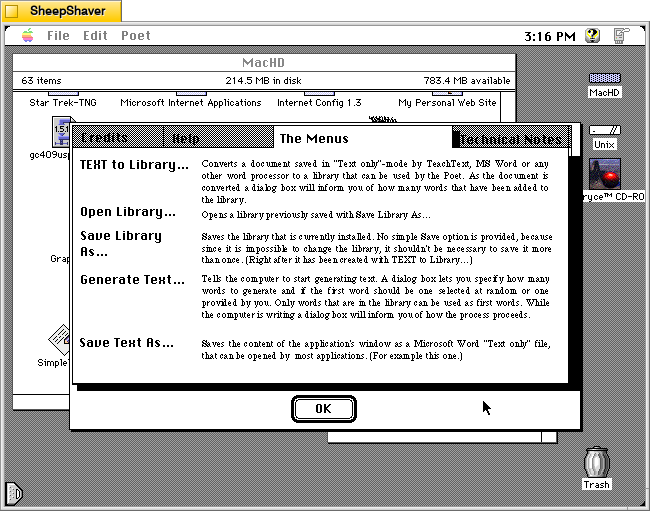

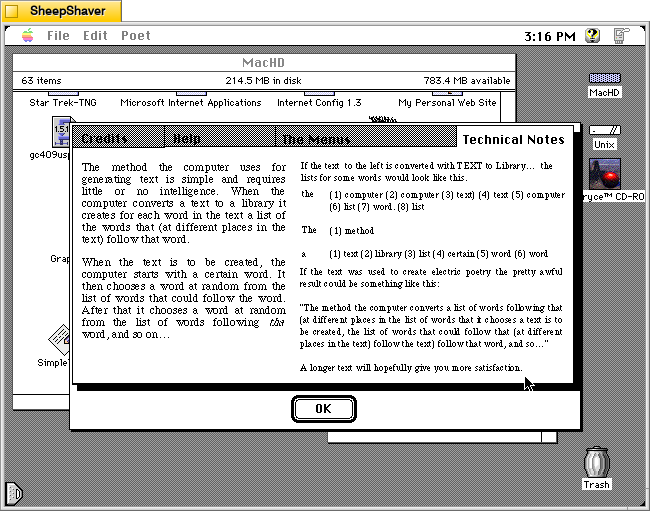

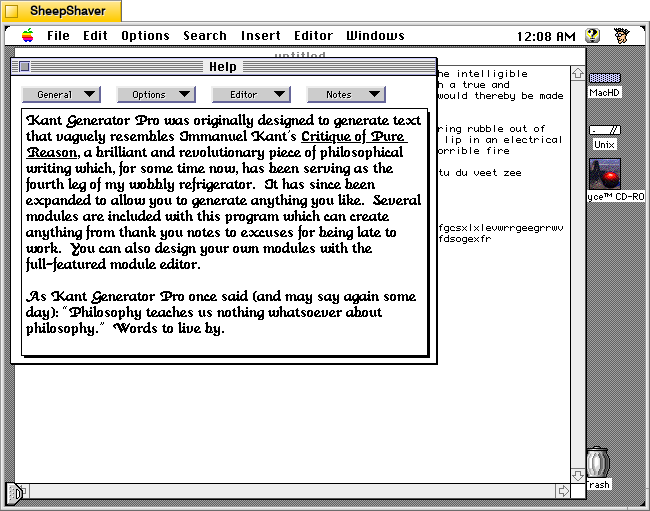

According to the program’s built-in Help (shown in a screenshot down the page):

Kant Generator Pro was originally designed to generate text that vaguely resembles Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, a brilliant and revolutionary piece of philosophical writing which, for some time now, has been serving as the fourth leg of my wobbly refrigerator. It has since been expanded to allow you to generate anything you like. Several modules are include with this program which can create anything from thank you notes to excuses for being late to work. You can also design your own modules with the full-featured module editor. And on a saved copy of Pilgrim’s personal website from 21 Dec. 1996, he writes the following about Kant Generator Pro:

Purpose: to generate pseudo-Kantian philosophy based on Kant's vocabulary and sentence structure in the "Critique of Pure Reason". Anyone who has been subjected to Kant (voluntarily or otherwise) will appreciate the humor in the gibberish this program outputs. Also includes a module editor so you can create your own generation modules.

Kant Generator is quickly becoming my most popular program (although it is still in third place behind Startup Screen Picker and Shutdown FX), especially among philosophy students, graduates, and professors. When I showed it (off) to my professor for my Kant course, he immediately started describing something he had written years ago to achieve a similar result, though by a completely different method. Other professors from across the country have praised it, saying they will use it in their introductory philosophy courses to 'stimulate interest in philosophy'. I guess every little bit helps.

I am slowly but steadily adding more modules to Kant Generator Pro. Version 1.1 added a Husserl module, as well as "thank you" note module (which occurred to me while procrastinating writing my Christmas thank you notes). Version 1.2 added an "excuses" module, written by Mike W. Miller. Version 1.3 added a Swedish Kant module, which is just the original Kant module with all the references and instantiations converted into Swedish Chef talk. (Yes, I used the code from Chef, and yes, I automated the process to cycle through all the instantiations and convert them, and no, you can't have the code. Just what we need is people running around converting all their KGP modules to Swedish Chef, or WAREZ, or Fudd...) Version 1.3 also added scripting support; anyone who wants to set up a WWW page and call Kant Generator Pro with a CGI interface through AppleScript has my permission as long as you send me your CGI interfacing code.

It's very exciting to have other people writing modules for Kant Generator Pro, if nothing else because it means I don't have to do anything for the program to keep improving. Suggestions for future philosopher modules (or anything else) are always appreciated, although I am reluctant to write modules of philosophers I haven't studied myself. Satire is the sincerest form of flattery, but also the most difficult... The source code for Kant Generator Pro is also available bundled with the application in the Info-Mac repository here.

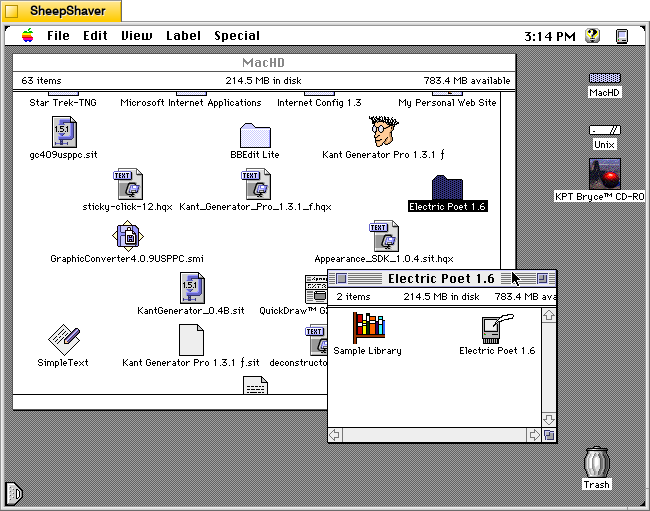

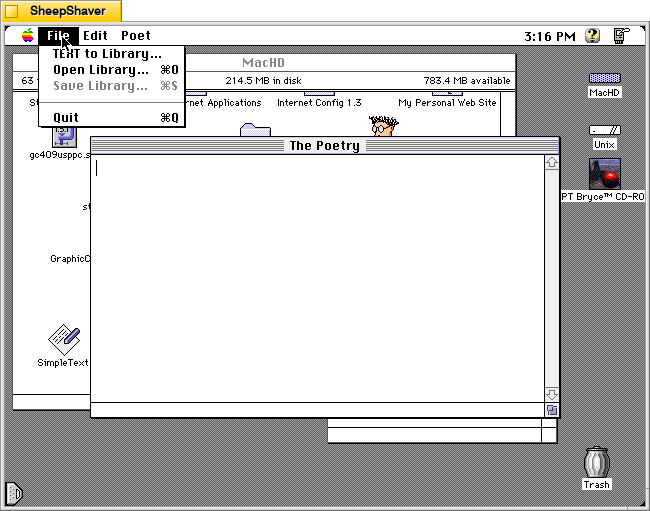

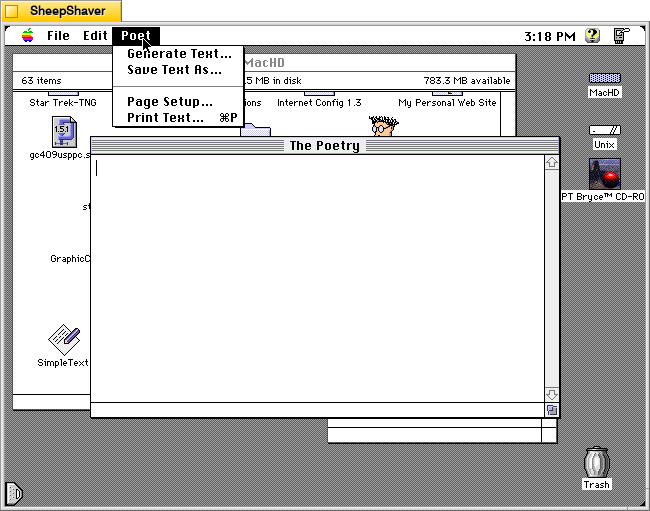

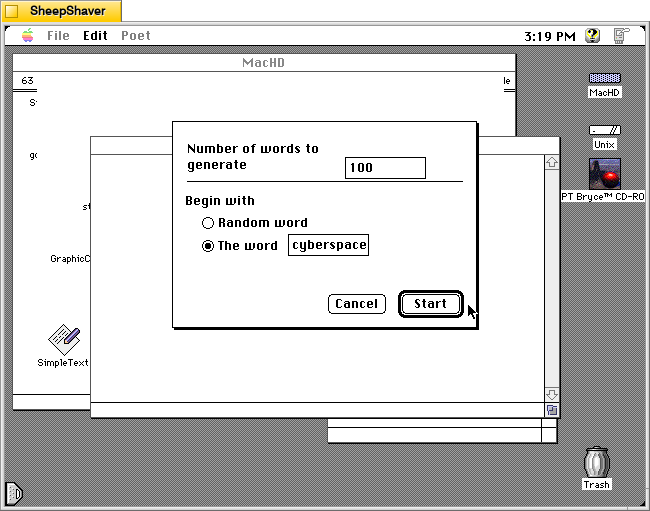

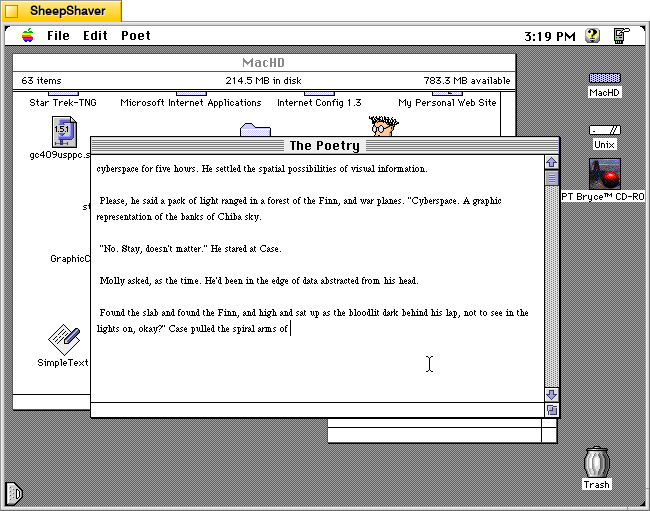

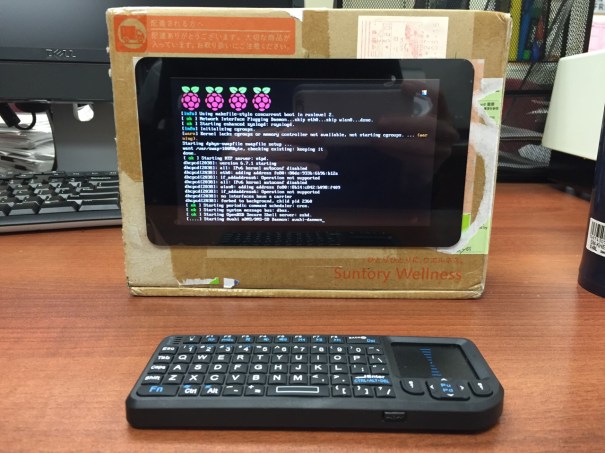

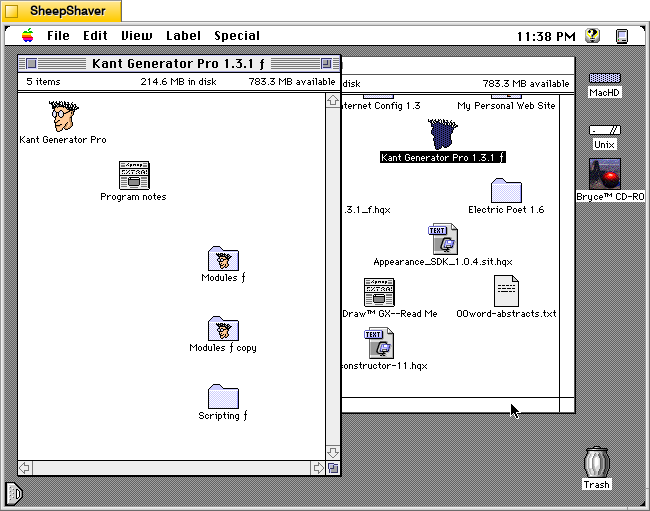

Below, I’ll annotate screenshots of the application running on an installation of Macintosh System Software 7.5.5 on the PPC emulator SheepShaver hosted by Debian 12 Bookworm with the Xfce Haiku Alpha window theme active.

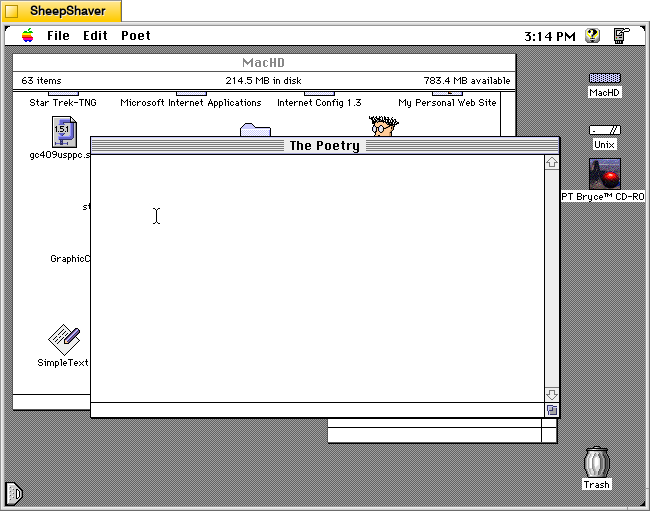

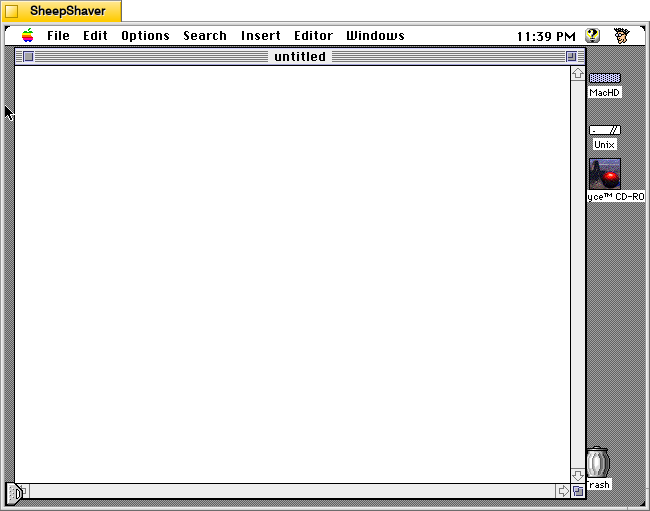

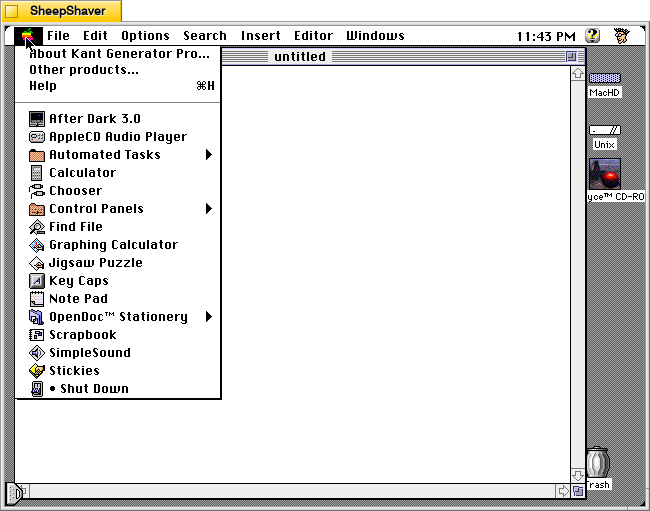

After opening Kant Generator Pro, the user is presented with a text entry window much like in any text or word processing software. One can enter text, but to have the program generate text, one needs to use the menus: first, to select the text generation module from the Options menu, and then, to select from the type of text to generate from the Insert menu.

Clicking on the Apple menu gives you options for About Kant Generator Pro, Other products, and Help.

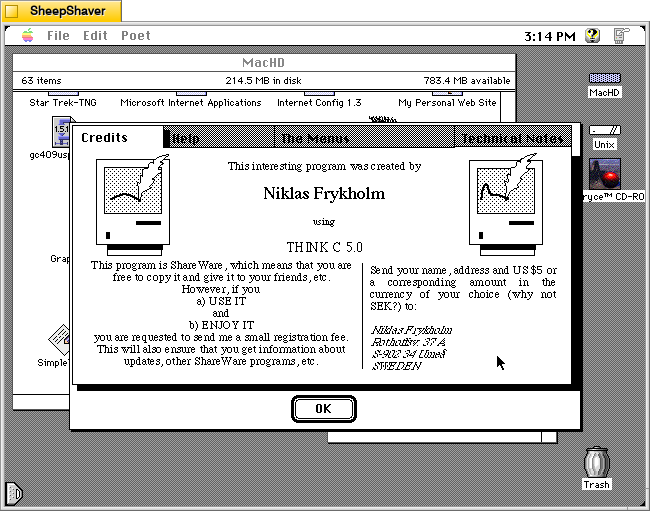

Opening the About window from the Apple menu features a scrolling credits and copyright notice.

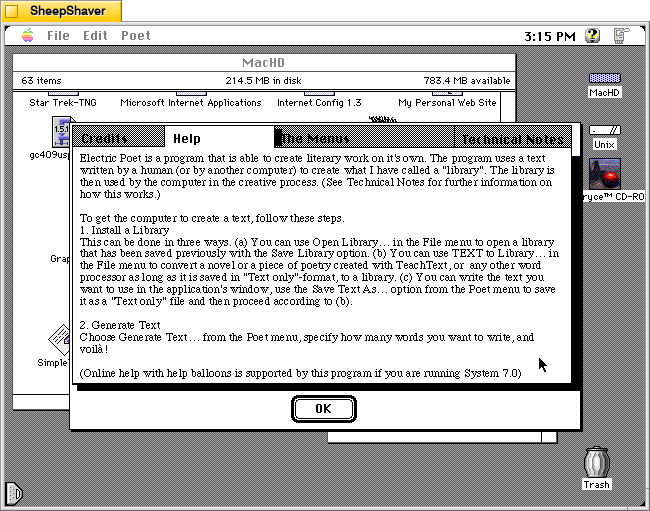

Selecting Help from the Apple menu provides lots of useful information about how to use Kant Generator Pro to generate text, how to edit the modules that it uses for text generation, and technical information about the design of the program.

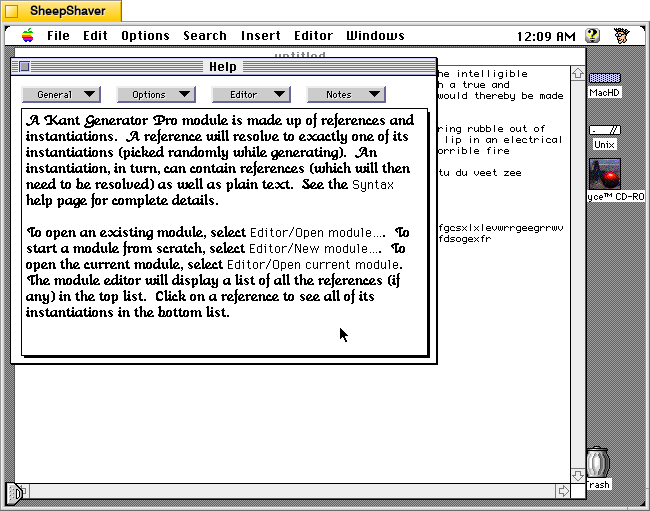

Choosing Editor > Getting Started on the Help window shows the information displayed above. Like Electric Poet, which I wrote about yesterday here, Kant Generator Pro relies on randomness, but unlike Electric Poet, Kant Generator Pro relies on more structure in building relationships between words and strings of text by editing a given Module (like Electric Poet’s Library). But where Kant Generator Pro gets really interesting is in how the responses can be engineered while editing the Module to reference and nest references within references.

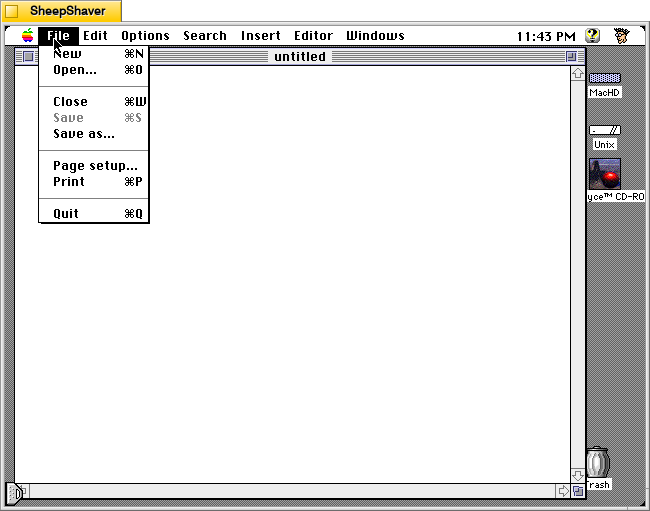

The File menu gives you access to basic file operations.

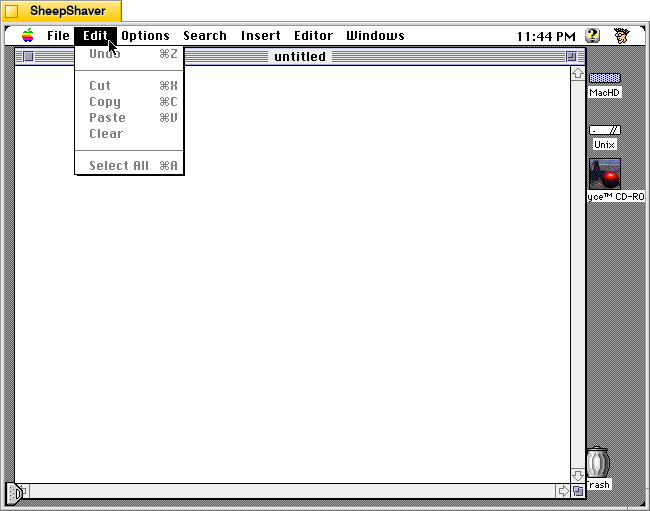

The Edit menu has basic edit operations.

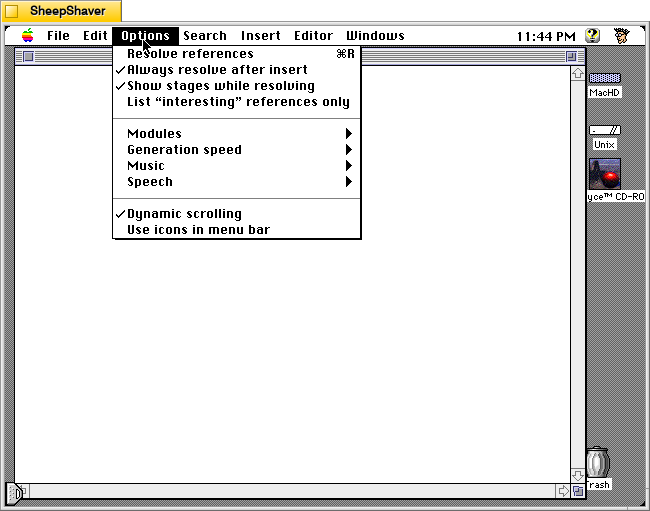

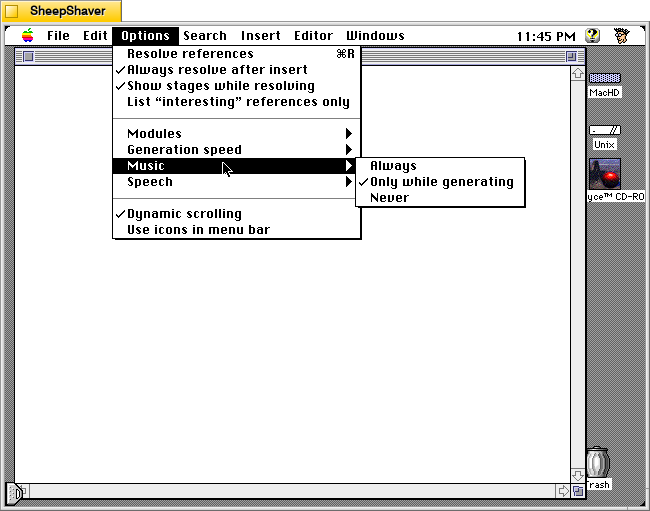

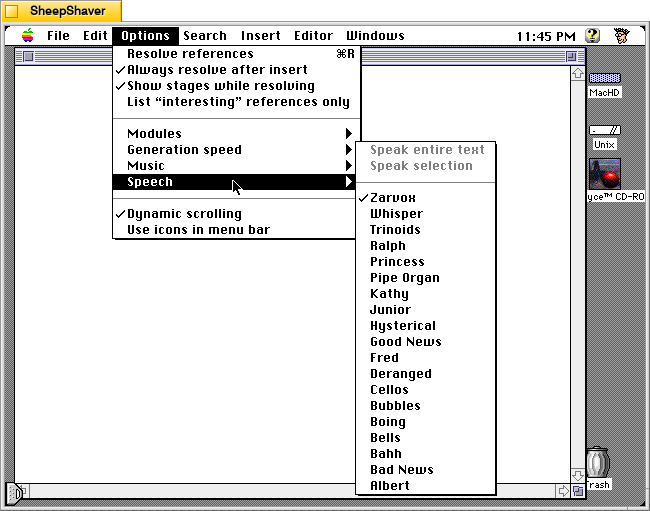

The Options menu controls Kant Generator Pro’s primary feature–the Module used for text generation, but it also gives the user options for how fast it generates text, whether music is played or not while generating text, and to speak the generated text a voice with Apple’s Text-to-Speech technology.

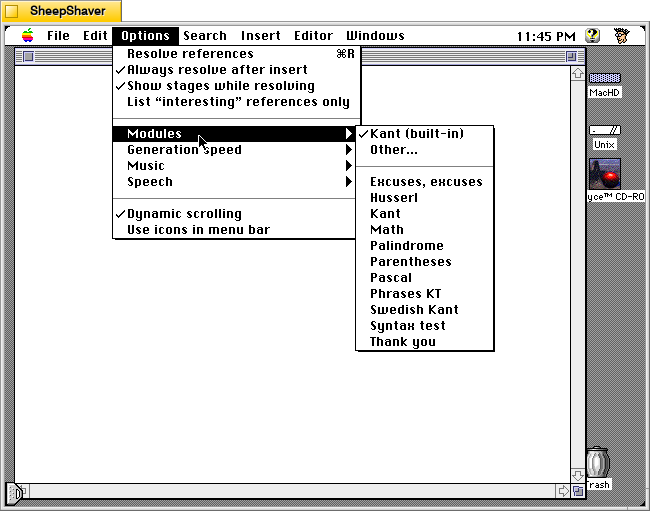

In the Options menu > Modules, the user chooses the text generator module to use. The Program Notes file (dated 26 Jun. 1995) included with the application describes the included modules:

Kant Generator Pro has the built-in capability to generate enormous amounts of Kantian gibberish, but if you'd like to play with generating your own text, it also lets you create, edit, and use external modules. There are several modules included in this release:

Kant: this is exactly the same as the built-in Kant module, except that you can edit it. The most general reference is §ion.

Swedish Kant: this is the same as the Kant module, except that all references names and text have been converted to mock Swedish Chef (as featured in my program Dialectic, which should be available wherever you got this package). The most general reference is &secshun.

Husserl: a module which emulates Edmund Husserl, a 20th-century phenomenologist. The most general reference is §ion.

Thank You: a module which generates thank-you notes for all occasions. The most general reference is &thank-you-note.

Excuses, excuses: a module which generates for excuses explaining exactly why you can't come to work. The most general reference is &Yet-Another-Excuse. Written by Mike W. Miller.

Math: a module which generates algebraic equations using +, -, *, /, parentheses, and three variables X, Y, and Z. The most general reference is &term. Written by David Scheidt (the same friend who discovered that he had 19 copies of the GPL).

Palindrome: a modules which generates palindromes (strings which spell the same backwards and forwards). The most general (and only) reference is &palindrome. Written by David Scheidt.

Pascal: a module which generates syntactically correct statements in the Pascal programming language. The most general reference is &pstate. Written by David Scheidt.

Parentheses: a module which generates strings of balanced parentheses. The most general reference is &balanced-parens. Written by David Scheidt.

Syntax test: this is a sample module which gives examples of the different forms of syntax which Kant Generator Pro can deal with. All the references are relevant, but you won't get much out of them unless you look at them in the module editor first.

If you'd like to create your own modules, poking around with these should be enough to get you started. There are several pages of help in the Kant Generator Pro application which talk about building modules, and I also support balloon help for all the menus. If you're still confused, drop me a line (my e-mail address is in the application's help section) and I'll try to help.

The Options menu > Music has options for Always, Only while generating, and Never.

The Options menu > Speech selection pulls available voices from Apple’s Text-to-Speech (if installed on the Macintosh) to give users an opportunity to have the generated text read aloud.

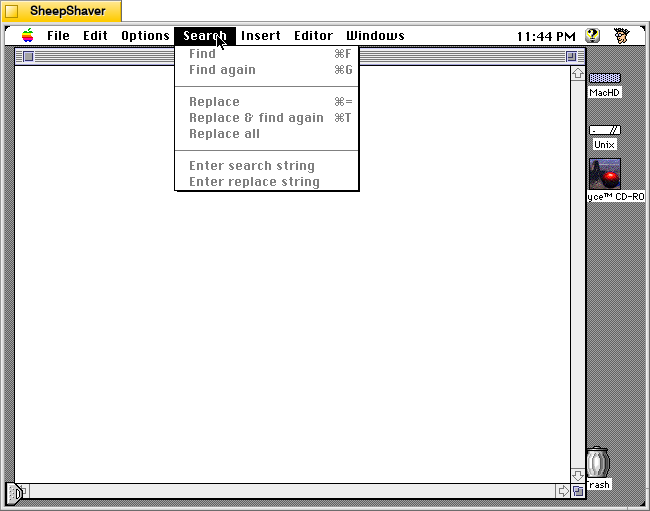

The Search menu gives users an easy way to find and replace text in the text generation window (but not the Editor window shown further below).

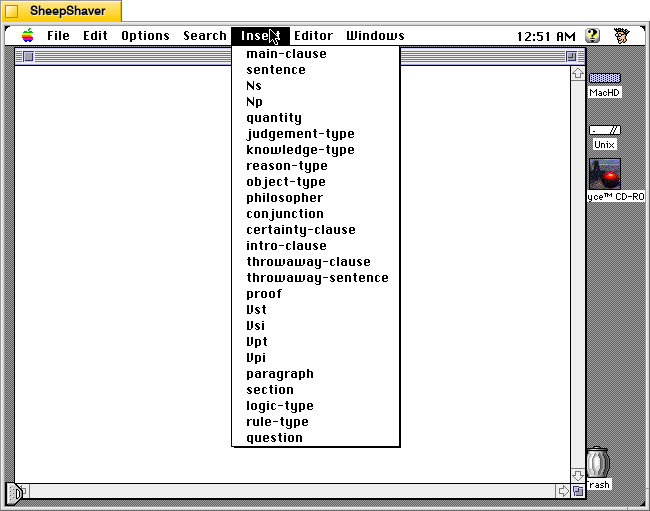

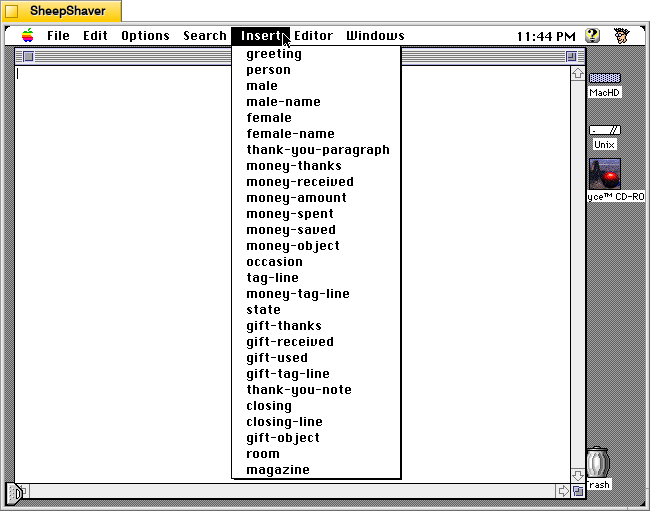

The Insert menu changes based on which Module the user selects after opening Kant Generator Pro. This menu is what directs Kant Generator Pro to generate text based on the text corpus and engineered relationships in the Module. Kant Generator Pro uses randomness to piece together options within the corpus and those established relationships to string words together into phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and sections. The above options in the Insert menu are for the Kant Module.

The Insert menu options shown above are for the Thank You Module.

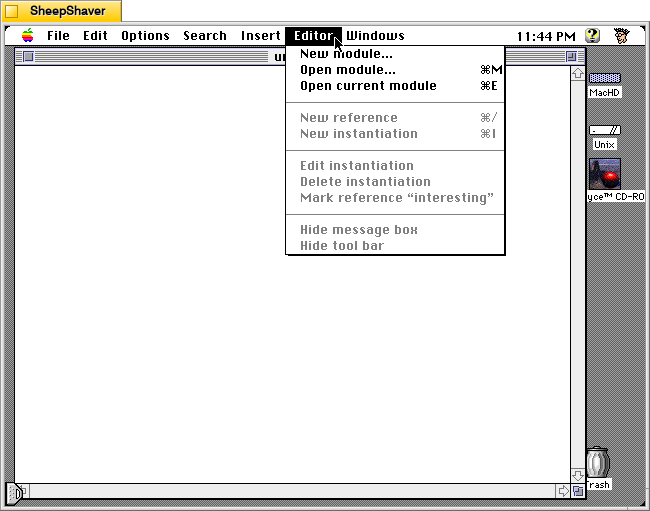

The Editor menu gives options to create a new module or open a module in the Editor window.

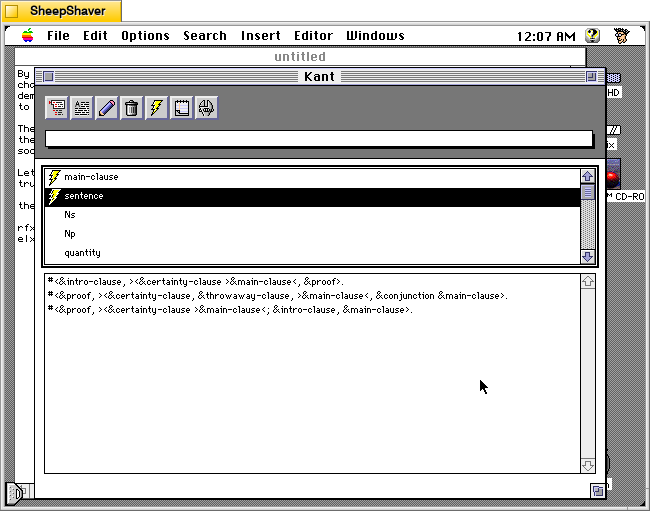

The Editor window for a Module is where the end user can construct new References (top pane) and Instantiations (lower pane). You can see in the lower pane how References string together other References and Instantiations within References to give the generated text structure.

The Window menu allows the user to switch between multiple open files in different windows.

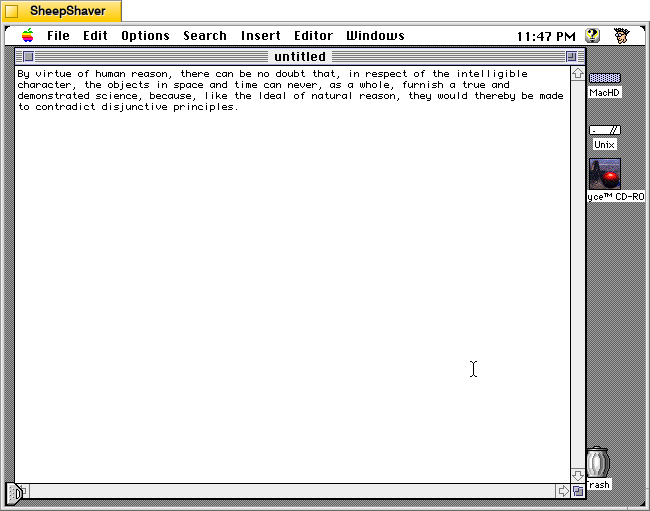

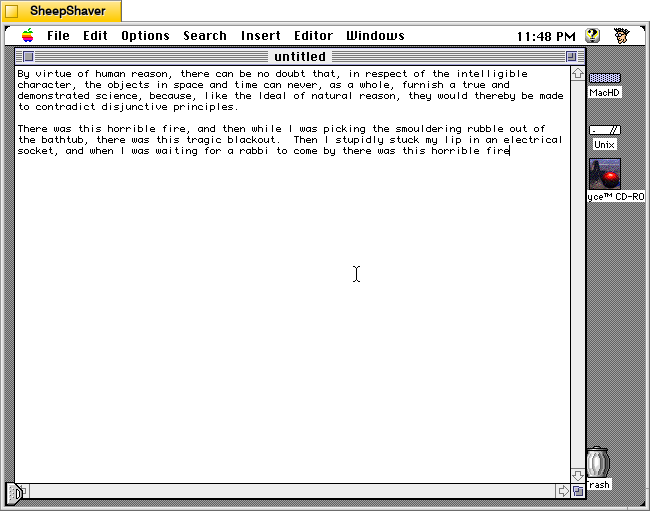

Using the Kant Module, I used the application to generate the sentence above.

Using the Excuses, excuses Module, I used the program to generate the above outlandish excuse.

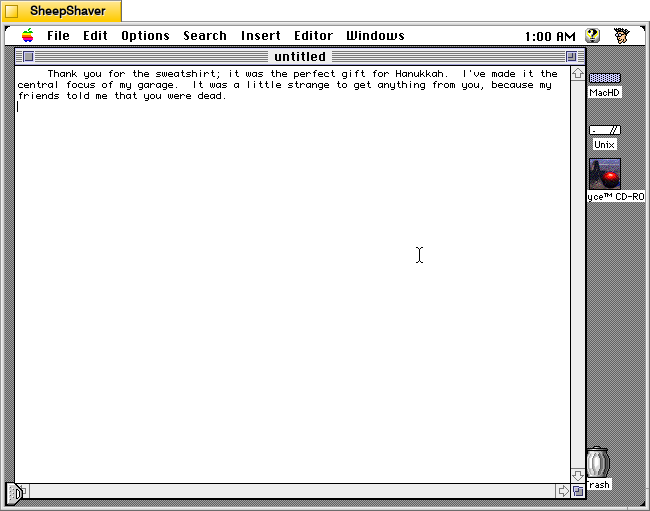

Finally, using the Thank You Module, I generated the rather strange gift thank you.

Like Electric Poet and large language model (LLM) artificial intelligence today, there is some trial-and-error involved. Electric Poet and Kant Generator Pro rely on a corpus of text, a system of relationships, and randomness to select what word or phrase goes next given a set of rules. In a sense, LLMs aren’t that much different except in scale. Based on a given LLM’s training, the relationships between words (or tokens) are far more complex. The hidden layers of an LLM construct relationships that are not simply 1-to-1. Analogous to neurons in our brains, the connections and weights for each connection between tokens are vast and labyrinthine.

Nevertheless, I can imagine Electric Poet and Kant Generator Pro being used today–over 25 years after being first developed in the latter’s case–as a tool to help students think about how text generation can work in a very simplified manner. This can be paired with sentence diagramming of some of their own writing, which can be duplicated within Kant Generator Pro as a “Me” Module that can reproduce one’s own writing. Then, students can advance to more complicated topics with how LLMs are trained on big data to create models that are magnitudes more sophisticated than their Library for Electric Poet or Module for Kant Generator Pro. Throughout the process, an important reminded needs to be reinforced–there is no intelligence in these Macintosh programs or LLMs as they currently exist. The old and the new generate text based on rules applied to models–the former being simple and the latter being much more complex, but in both cases not having awareness or self-direction. Though, it seems like we are going in the direction of self-awareness and self-direction far more quickly than seems safe to me.