As I wrote about recently about my summertime studying and documented on my generative artificial intelligence (AI) bibliography, I am learning all that I can about AI–how it’s made, how we should critique it, how we can use it, and how we can teach with it. As with any new technology, the more that we know about it, the better equipped we are to master it and debate it in the public sphere. I don’t think that fear and ignorance about a new technology are good positions to take.

I see, like many others do, that AI as an inevitable step forward with how we use and what we can do with computers. However, I don’t think that these technologies should only be under the purview of big companies and their (predominantly) man-child leaders. Having more money and market control does not mean one is a more ethical practitioner with AI. In fact, it seems that some industry leaders are calling for more governmental oversight and regulation not because they have real worries about AI’s future development but instead because they are in a leadership position in the field and likely can shape how the industry is regulated through industry connections with would-be regulators (i.e., the revolving door of industry-government regulation in other regulatory agencies).

Of course, having no money or market control in AI does not mean one is potentially more ethical with AI either. But, ensuring that there are open, transparent, and democratic AI technologies creates the potential for a less skewed playing field. While there’s the potential for abuse of these technologies, having these available to all creates the possibility for many others to use AI for good. Additionally, if we were to keep AI behind locked doors, only those with access (legally or not) will control the technology, and there’s nothing to stop other countries and good/bad actors in those countries from using AI however they see fit–for good or ill.

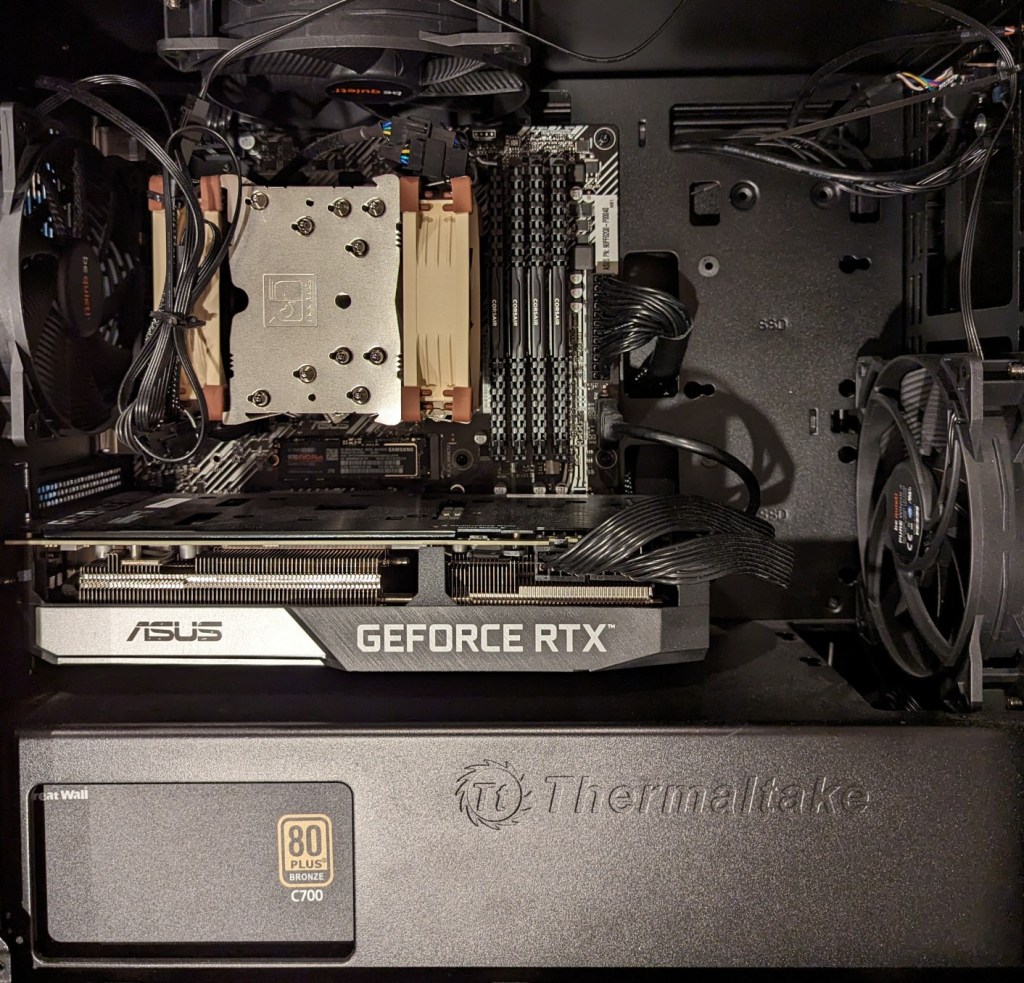

To play my own small role in studying AI, using generative AI, and teaching about AI, I wanted to build my own machine learning-capable workstation. Before I made any upgrades, I maxed out what I could do with a Asus Dual RTX 3070 8GB graphics card and 64GB of RAM for the past few months. I experimented primarily with Stable Diffusion image generation models using Automatic1111’s stable-diffusion-webui and LLaMA text generation models using Georgi Gerganov’s llama.cpp. An 8GB graphics card like the NVIDIA RTX 3070 provides a lot of horsepower with its 5,888 CUDA cores and memory bandwidth across its on-board memory. Unfortunately, the on-board memory is too small for larger models or adjusting models with multiple LORA and the like. For text generation, you can layer some of the model on the graphic’s card memory and your system’s RAM, but this is inefficient and slow in comparison to having the entire model loaded in the graphics card’s memory. Therefore, a video card with a significant amount of VRAM is a better solution.

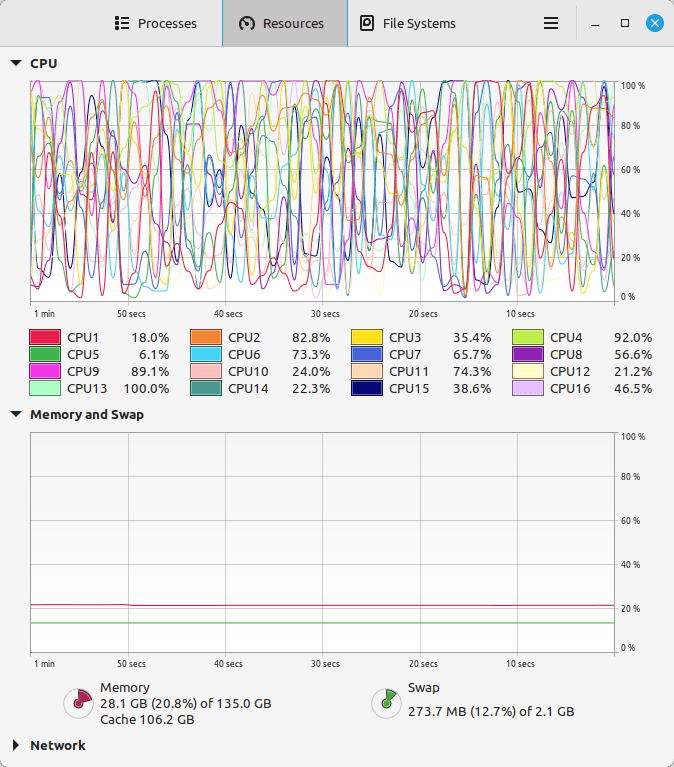

For my machine learning focused upgrade, I first swapped out my system RAM for 128GB DDR4-3200 (4 x 32GB Corsair shown above). This allowed me to load 65B parameters into system RAM with my Ryzen 7 5800X 8 core/16 thread CPU to perform the operations. The CPU usage while it is processing tokens on llama.cpp looks like an EEG:

While running inference on the CPU was certainly useful for my initial experimentation and the CPU usage graph looks cool, it was exceedingly slow. Even an 8 core/16 thread CPU is ill-suited for AI inference in part due to how it lacks the massive parallelization of graphics processing units (GPUs) but perhaps more importantly due to the system memory bottleneck, which is only 25.6 GB/s for DDR4-3200 RAM according to Transcend.

Video cards, especially those designed by NVIDIA, provide specialized parallel computing capabilities and enormous memory bandwidth between the GPU and video RAM (VRAM). NVIDIA’s CUDA is a very mature system for parallel processing that has been widely accepted as the gold standard for machine learning (ML) and AI development. CUDA is unfortunately, closed source, but many open source projects have adopted it due to its dominance within the industry.

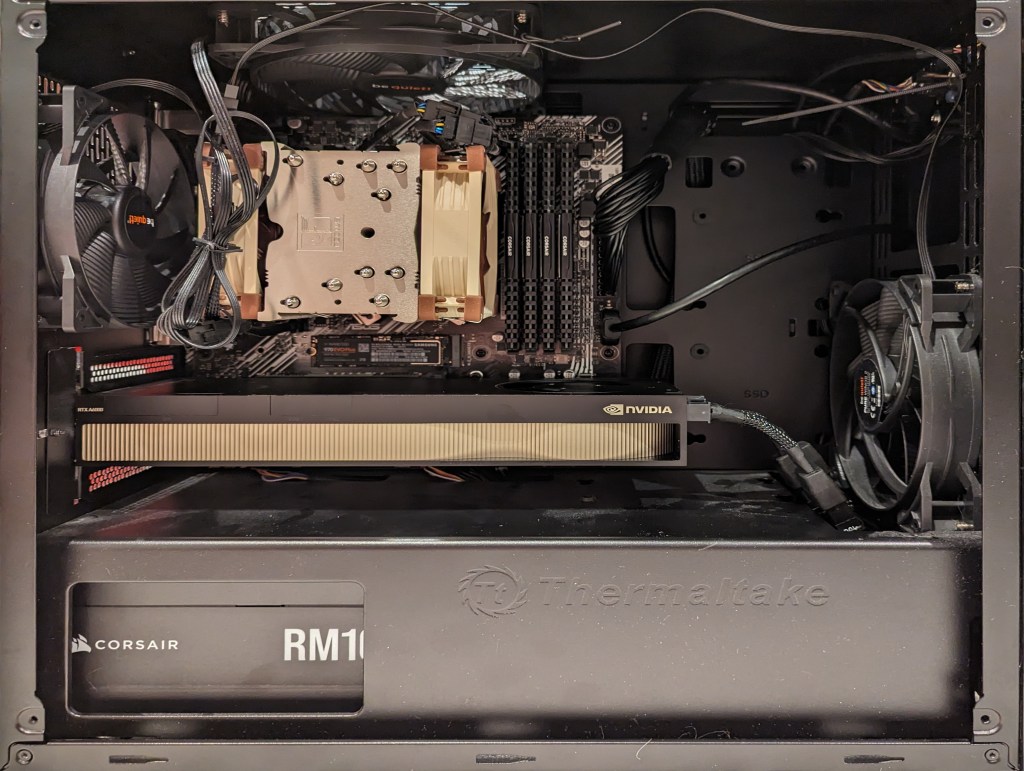

My primary objective when choosing a new video card was that it had enough VRAM to load a 65B LLaMA model (roughly 48GB). One option for doing this is to install two NVIDIA RTX 3090 or 4090 video cards with each having 24GB of VRAM for a total of 48GB. This would solve my needs for running text generation models, but it would limit how I could use image generation models, which can’t be split between multiple video cards without a significant performance hit (if at all). So, a single card with 48GB of VRAM would be ideal for my use case. Three options that I considered were the Quadro 8000, A40, and RTX A6000 Ampere. The Quadro 8000 used three-generation-old Turing architecture, while the A40 and RTX A6000 used two-generation-old Ampere architecture (the latest Ada architecture was outside of my price range). The Quadro 8000 has memory bandwidth of 672 GB/s while the A40 has 696 GB/s and the A6000 has 768 GB/s. Also, the Quadro 8000 has far fewer CUDA cores than the other two cards: 4,608 vs. 10,572 (A40) and 10,752 (A6000). Considering the specs, the A6000 was the better graphics card, but the A40 was a close second. However, the A40, even found for a discount, would require a DIY forced-blower system, because it is designed to be used in rack mounted servers with their own forced air cooling systems. 3D printed solutions that mate fans to the end of an A40 are available on eBay, or one could rig something DIY. But, for my purposes, I wanted a good card with its own cooling solution and a warranty, so I went with the A6000 shown below.

Another benefit to the A6000 over the gaming performance-oriented 3090 and 4090 graphics cards is that it requires much less power–only 300 watts at load (vs ~360 watts for the 3090 and 450 watts for the 4090). Despite this lower power draw, I only had a generic 700 watt power supply. I wanted to protect my investment in the A6000 and ensure it had all of the power that it needed, so I opted to go with a recognized name brand PSU–a Corsair RM1000x. It’s a modular PSU that can provide up to 1,000 watts to the system (it only provides what it is needed–it isn’t using 1000 watts constantly). You can see the A6000 and Corsair PSU installed in my system below.

Now, instead of waiting for 15-30 minutes for a response to a long prompt ran on my CPU and system RAM, it takes mere seconds to load the model on the A6000’s VRAM and generate a response as shown in the screenshot below of oobabooga’s text-generation-webui using the Guanaco-65B model quantized by TheBloke to provide definitions of science fiction for three different audiences. The tool running in the terminal in the lower right corner is NVIDIA’s System Management Interface, which can be opened by running “nvidia-smi -l 1”.

I’m learning the programming language Python now so that I can better understand the underlying code for how many of these tools and AI algorithms work. If you are interested in getting involved in generative AI technology, I recently wrote about LinkedIn Learning as a good place to get started, but you can also check out the resources in my generative AI bibliography.