MacProse is a text generating application that focuses on sentences for Macintosh that Charles O. Hartman, Lucy Marsh Haskell ’19 Professor Emeritus of English at Connecticut College, programmed to conduct research for his book titled Virtual Muse: Experiments in Computer Poetry (Wesleyan UP, 1996). It is based on an earlier program for MS-DOS called simply PROSE. While MacProse is no longer available on Hartman’s Programs and Programming page on his personal website, thankfully there is a copy saved on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine here.

For such a compact application, MacProse does some interesting things with creating sentences–one at a time or as many as it can until the user presses the mouse button. Then, the user can save all of the output or copy individual sentences. When clicking a sentence, a diagram of how the sentence is put together is shown in the separate Sentence Tree window. Also, the user can design sentences using a built-in workflow.

In the accompanying “MacProse Doc,” Hartman writes, “MacProse is a Macintosh version of the old Prose program for DOS computers, described in The Virtual Muse. It generates syntactically correct English sentences, whose structure and vocabulary are both randomized” (par. 1).

He notes that “MacProse should run on any Macintosh with system software version 7.1 or later. It requires very little RAM and doesn’t much care about CPU speed.”

Considering some of the other text generating programs for Macintosh that I’ve written about before, MacProse is lightweight like Electric Poet 1.6, has an extensible architecture like Kant Generator Pro 1.3.1 and McPoet 5.1 (which is where I learned about MacProse!).

While the program certainly has a lot of potential as a generative text tool, Hartman writes in Virtual Muse, “I hope the book makes it clear that–for me and I hope for interested readers–the point isn’t the programs themselves (which are fairly simple and not particularly original) but the uses that can made of them” (ix).

Below, I’ll annotate screenshots of the application running on an installation of Macintosh System Software 7.5.5 on the PPC emulator SheepShaver hosted by Debian 12 Bookworm with the Xfce Haiku Alpha window theme active.

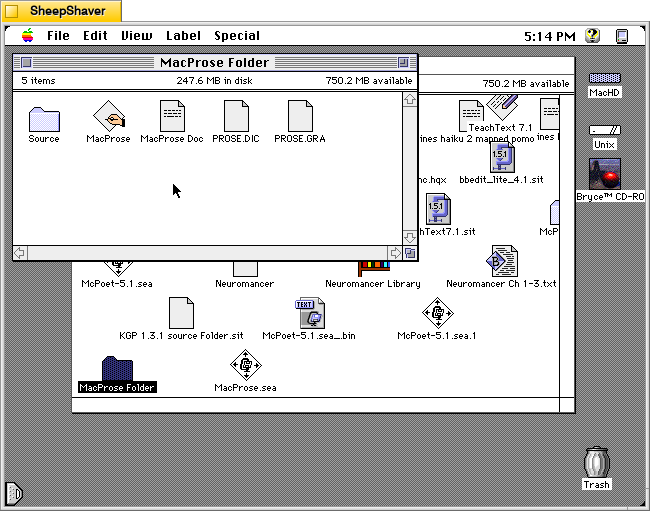

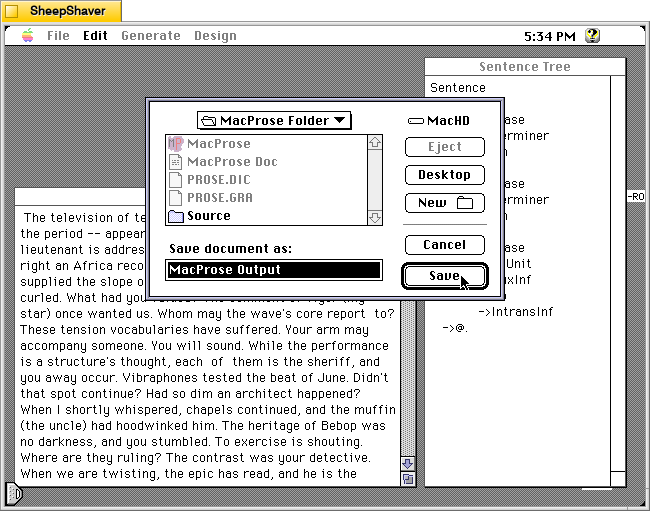

The MacProse Folder contains the MacProse application, MacProse Doc (i.e., Read Me with info and help), PROSE.DIC (the word dictionary file used by the application), PROSE.GRA (the grammar file used by the application), and the Source folder (this source code has to be used with the EasyApp framework included with Jim Trudeau’s Programming Starter Kit for Macintosh, Hayden Books, 1995, which is copyrighted and not included).

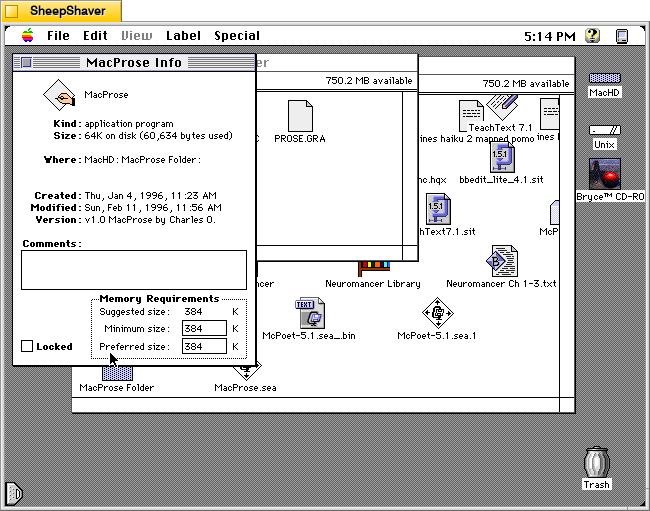

Like Electric Poet, MacProse is a very lean program. It is only 60,634 bytes and it uses very little RAM: 384 K. The MacProse folder, including the source code, is only 314,098 bytes.

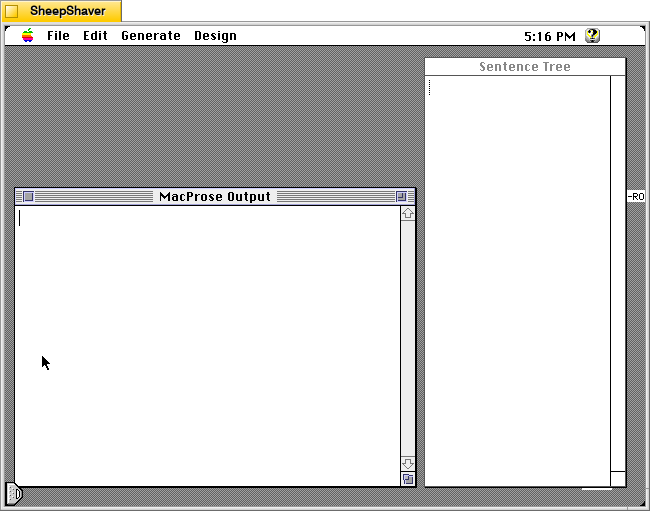

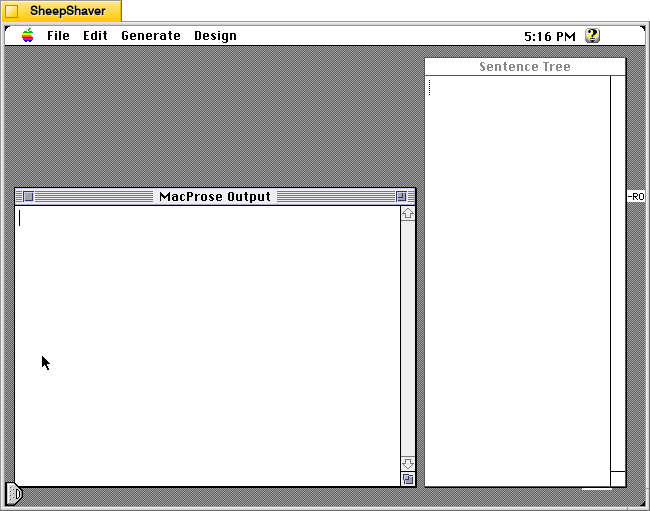

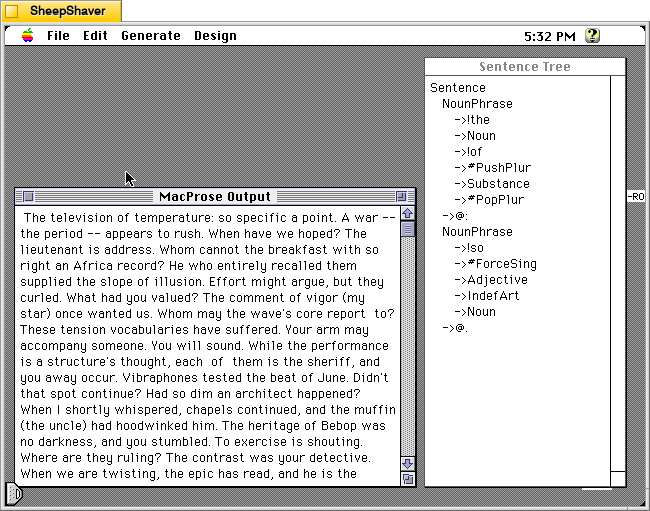

When MacProse is first launched, the user is presented with these two windows: MacProse Output (where generated text appears–each sentence being selectable and having its own structure) and Sentence Tree (where each sentence’s structure is diagrammed).

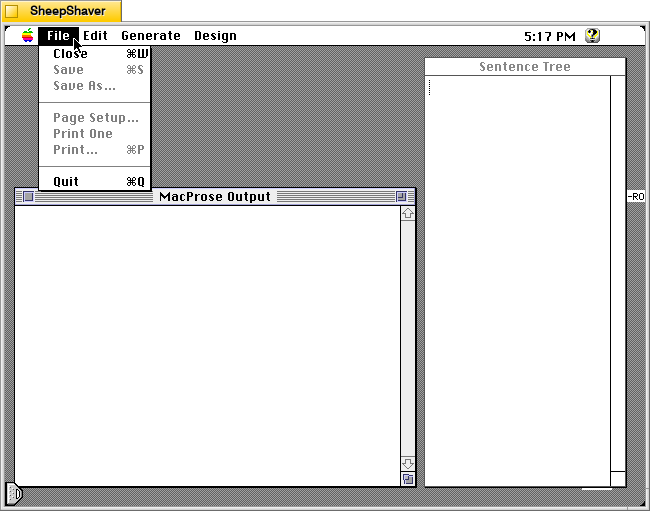

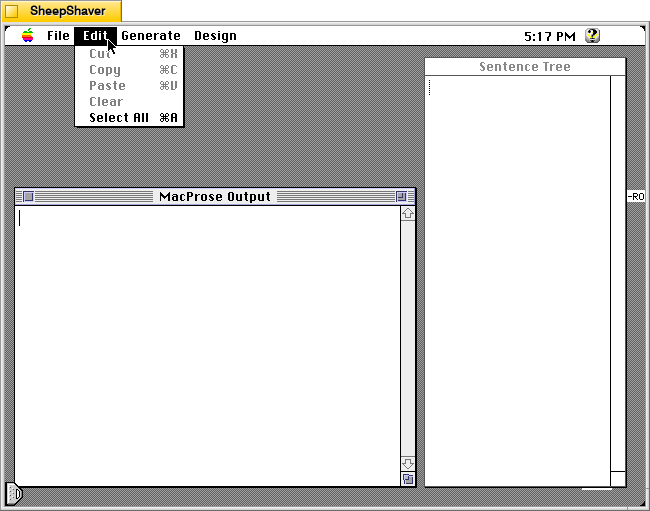

It is certainly has a spartan appearance, especially compared to McPoet 5.1. Hartman explains: “As Macintosh programs go, MacProse is brain-damaged and downright user-unfriendly. Since it has no input, and since its output is pretty rigidly organized as sentences, all kinds of interaction a Mac user expects are simply missing. The File menu contains only Save and Print and Quit (there’s nothing to Open). The Edit menu has the usual Cut, Copy, Clear, and Paste, but they work peculiarly–only on a whole sentence at a time. Selecting text in the output window is strange for the same reasons, as described below. And though the Output window looks like a text-editing window, you can’t type in it. All of these oddities follow from the basic peculiarity of MacProse’s function in life, which is that of Virtual Muse” (“MacProse Doc,” par. 4).

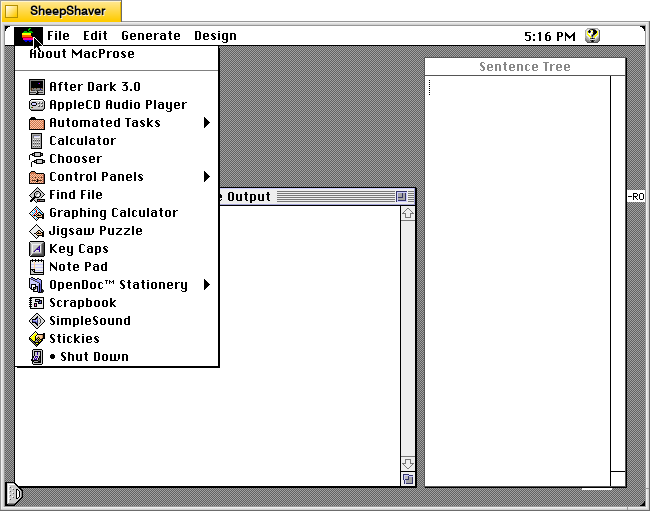

The Apple menu has an option for “About MacProse.”

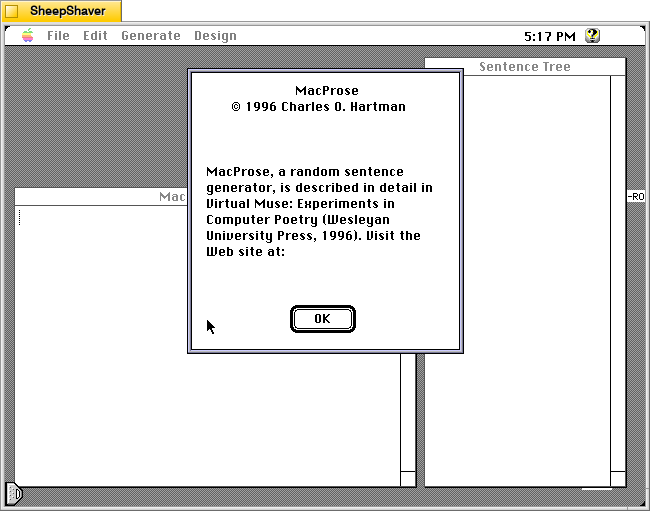

The About MacProse window gives copyright information for 1996 Charles O. Hartman, and explanation about its purpose: “MacProse, a random sentence generator, is described in detail in Virtual Muse: Experiments in Computer Poetry (Wesleyan University Press, 1996). Visit the Web site at:” Perhaps because of the version of Mac OS that I’m running (System 7.5.5), the about window text and font aren’t what were expected and cut off the URL for the book’s website.

MacProse’s File menu has basic options for closing windows, saving the generated text, printing, and quitting the application.

The Edit menu has basic functions available, but as Hartman notes in the “MacProse Doc,” cut and copy work on a sentence basis–not on selectable words or phrases.

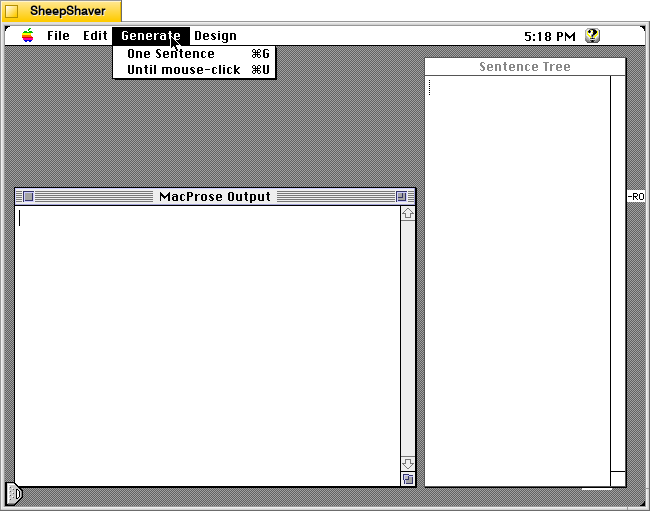

The Generate menu is what makes the magic happen with options to generate one sentence or to generate sentences until the mouse is clicked. Hartman explains:

“Generate has two commands: One Sentence (keyboard equivalent command-G) generates a single sentence, which is displayed in the Output window. The generation “tree” that produced the sentence is displayed in the Tree window. The other command, Until mouse-click (keyboard equivalent command-U) keeps generating sentences until you click the mouse button–or until the output buffer’s 32k limit is reached (about 600 sentences).

“When you have generated more than one sentence, a click with the mouse in any of them places that sentence’s tree in the Tree window. If you double-click a word (or mark of punctuation) in the output, the tree “leaf” that generated the word is highlighted in the Tree window. If you drag to select more than a word, one whole sentence is selected. You can then use Cut and Paste to move the sentence to a new place in the output; its tree information will follow it. If you click an item in the tree window, the corresponding word, or the entire rule’s clause or phrase if you click a predicate, is highlighted in the output window.

“MacProse never places a newly generated sentence, or a Pasted one, in the middle of an existing one; it moves the insertion point to the next sentence-start point” (“MacProse Doc,” par. 6-8).

The way that MacProse keeps each sentence as a unit with its own explainable design that remains linked to it within the application makes it unique among text generating applications of this era and its explainability reveals how it does what it does while also providing a pedagogical tool when using this program in the classroom as I intend to do.

After generating a bunch of sentences using the generate until a mouse click option, I clicked on the first sentence, “The television of temperature: so specific a point,” which shows its diagram in the Sentence Tree window to the right.

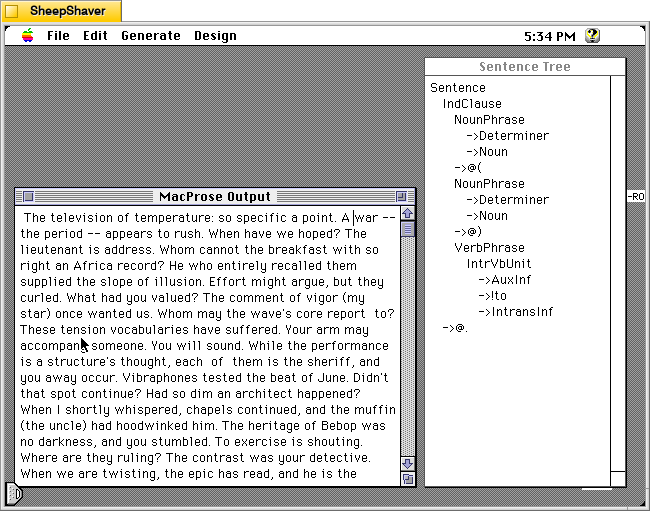

Then, I clicked on the second sentence, “A war–the period–appears to rush,” and its diagram, which is different than the first sentence’s, appears in the Sentence Tree window to the right.

I clicked on File > Save to save the MacProse Output window’s sentences as a text file. I couldn’t click the mouse quickly enough to stop it generating all of the following output:

“The television of temperature: so specific a point. A war — the period — appears to rush. When have we hoped? The lieutenant is address. Whom cannot the breakfast with so right an Africa record? He who entirely recalled them supplied the slope of illusion. Effort might argue, but they curled. What had you valued? The comment of vigor (my star) once wanted us. Whom may the wave’s core report to? These tension vocabularies have suffered. Your arm may accompany someone. You will sound. While the performance is a structure’s thought, each of them is the sheriff, and you away occur. Vibraphones tested the beat of June. Didn’t that spot continue? Had so dim an architect happened? When I shortly whispered, chapels continued, and the muffin (the uncle) had hoodwinked him. The heritage of Bebop was no darkness, and you stumbled. To exercise is shouting. Where are they ruling? The contrast was your detective. When we are twisting, the epic has read, and he is the partner of dance. When she stops, whom have those horses between a motel and the packrat included? We were charging the streams. When had the officers grinned? Had they stripped certain seats? So sufficient a man checkmates alternatives. He who is my child is town. You had obtained some sound tire; he who stumbled will demonstrate camera. The pincushion except the choice of guilt between a jungle and certain piles: cloth. He who wouldn’t talk promised her. They are palms. The column — shall the throat of error find the democracy between those apartments and these companions? The session of sin between the shirt and the shape wishes to achieve so guilty a charge. To escape might fit. Sky can interrupt them. When are these sisters staring? He who exchanged you thoroughly hung it. How have so higher a vibraphone worried? The frame of money has attacked a hall spirit. You have searched. We had visualized her; and so average a film was hastening, and the maple of death resumed it. To vanish was the heritage of ease. Had the conspiracy of dirt stopped? Communities open a Babbage. A parade motive (an illustration) didn’t extend; if night is offering, the weather is a wonderful pocket. The citizen of respect (my gentleman) waited, and to whisper was court. The version is their door between the head and these victories. Couldn’t that bedroom between the police and the horizon between those characters and the county cry? If the path between certain vigilantes and the age was science, the suspicion of town wouldn’t approach someone, and the food between another Turing and the incident had slid. Language (promise) can’t speak. Had you repaired this lover’s belt? Had you foiled truths between the avenue and the Babbage? I may droop. My succession: the reporter of atmosphere. They are those civic kingdoms. To burst cooked so local a sleuth between the side and a sidewalk. He who was computation along a sea paid to scheme. These structure communities hold him; and your theory above song: so middle a sidewalk. You were these foots. Why has April landed? He who was supporting its year like its audience was the brush of mass between the willow and the secretary. Plaster — iodine — bets so vacant an index; dawn repeats you. Anodes: the margins of sea. Since to sink can’t vacillate, that fist is the center. Every question claims to connect, but the end (entrance) will unclasp her chain throughout the prospect. To read was darkness; and steel was this vote. School governs them. To emerge was stumbling. When to rush emerges, to drive costs this. How can’t sacrifice swell? He who was the stress’s doctrine was the dancer. You exchanged these crystal windows. Prices briefly did, and impulses were the valleys. Have moments dreamed sacrifices? Whom has museum about its sheriff fed? Had certain pennies replaced certain exceptional tubes? Whom will so oral an epic visualize?”

As a whole, it is nonsense, but there are some short sentences, phrases, and word combinations that are interesting, thought provoking, and poetic. As I’ve said about these types of text generating programs (and image generating ones like KPT Bryce and Evolvotron) before, there is a lot of utility in these applications for inspiring or giving some raw material that we humans can use or build upon. They aren’t necessarily the end point of creation. They become a tool in the toolbox, a component within a larger workflow.

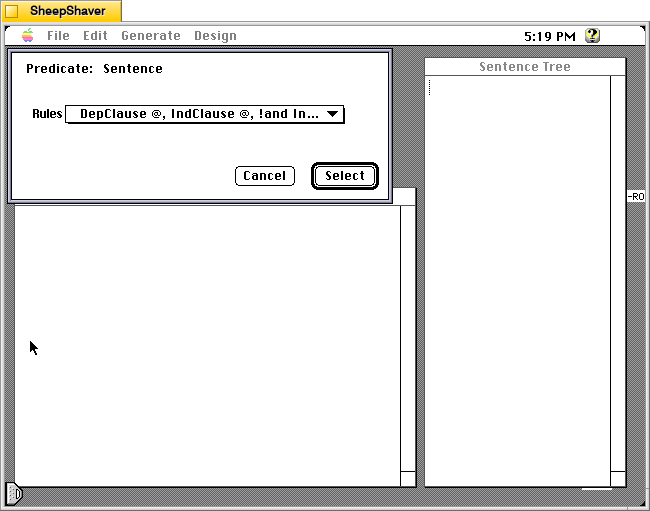

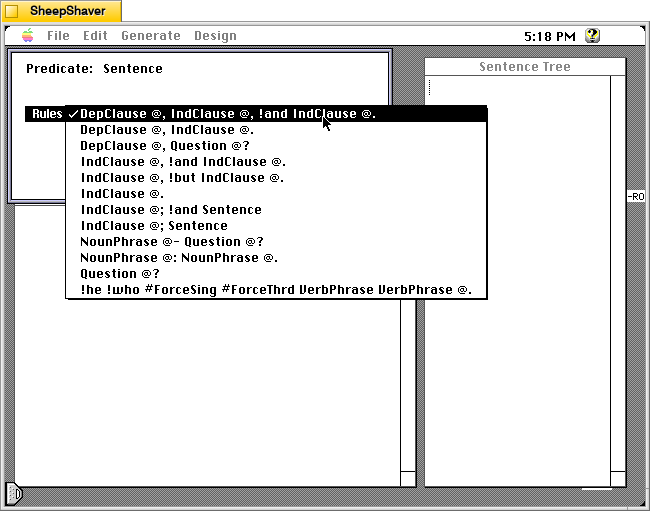

The other significant menu item is Design. Clicking on it and choosing “Design a sentence” brings up a window that guides you through your own design using the options available. Hartman explains how it work:

“The Design menu has only one item, Design Sentence (keyboard equivalent command-D). Instead of building the sentence’s grammatical template at random, this option lets you choose which rules to employ. The rules are contained in the grammar. Each line of the grammar defines a “predicate” with a series of components, each of which may be a “leaf” (an item that goes directly into the template) or another predicate, which must have a rule. The grammar contains several rules for each predicate; all predicates must be defined by at least one rule.

“Building a sentence, whether you do it or the computer does it at random, is a recursive process: first you choose a rule for the Sentence you want; then you choose a rule for each of the predicates that rule contains, and each of the predicates each of those rules contains, and so on, until you have completely defined the sentence’s structure.

“To help you do this, MacProse puts up a dialog box showing the predicate you’re defining, and a popup menu of all the available rules that define that predicate. The result of what you’ve done so far is displayed in the Tree window. When you’ve defined all the predicates by choosing a rule for each one, MacProse generates a sentence (by randomly consulting the Dictionary) that follows the structure you’ve built” (“MacProse Doc,” par. 9-11).

After choosing “Design Sentence,” the user is presented with this window.

The Design Sentence window has these options. Selecting from this list leads to further options.

I think MacProse is a really fascinating application that drills down into doing one thing well–writing sentences–and providing users an explanation about how it strung words together for each sentence. Now, I plan to read Hartman’s book to learn more before I think about how to incorporate it and the other text generating programs that I’ve written about in my future writing classes. There’s a lot of value in these older programs not just in terms of digital history preservation, but also in terms of their continuing usefulness whether it be as a creative writing tool or as a pedagogical tool for exploring ideas about how language works, looking how these programs are the progenitors for today’s generative artificial intelligence technologies, or learning how to use this software on modern computing hardware. To paraphrase Hartman, it’s not about the software. Instead, it’s about what you can do with the software.