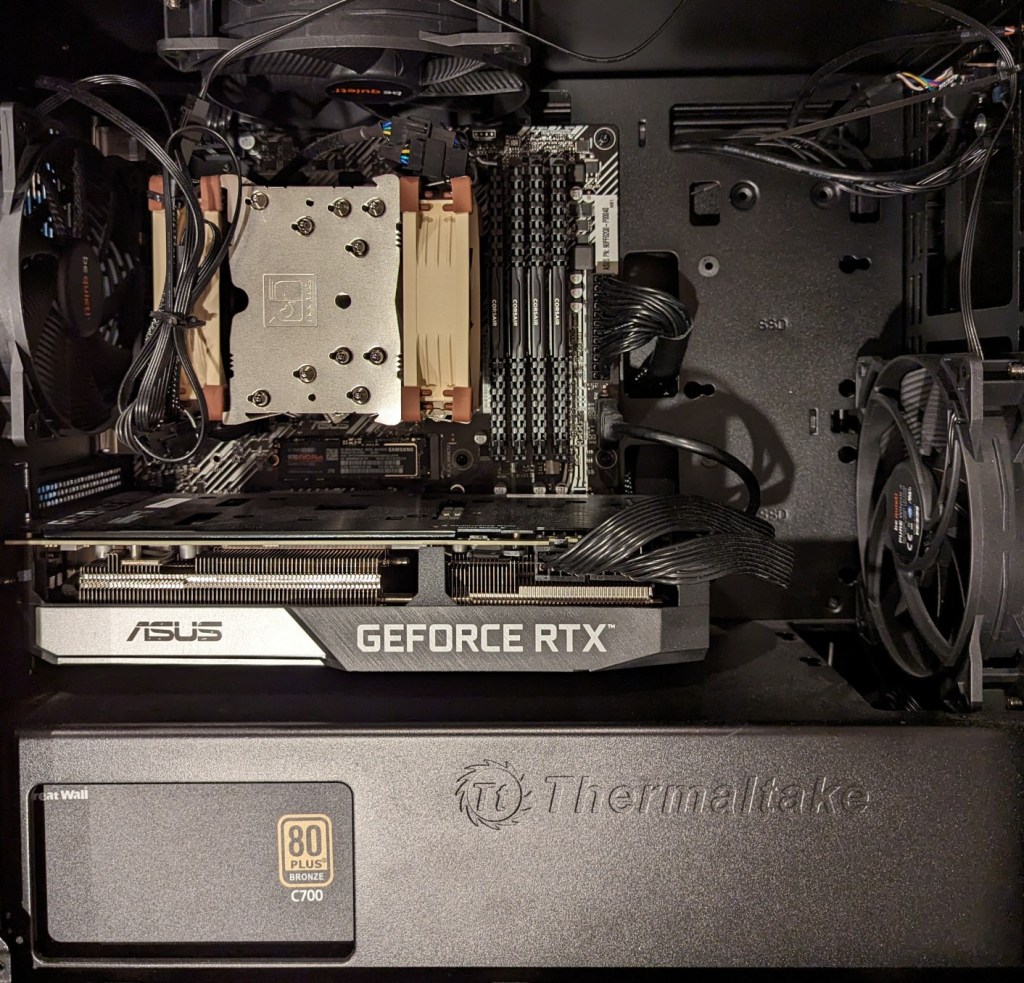

As I documented last year, I made a substantial investment in my computer workstation for doing local text and image generative AI work by upgrading to 128GB DDR4 RAM and swapping out a RTX 3070 8GB video card for NVIDIA’s flagship workstation card, the RTX A6000 48GB video card.

After I used that setup to help me with editing the 66,000 word Yet Another Science Fiction Textbook (YASFT) OER, I decided to sell the A6000 to recoup that money (I sold it for more than I originally paid for it!) and purchase a more modest RTX 4060 Ti 16GB video card. It was challenging for me to justify the cost of the A6000 when I could still work, albeit more slowly, with lesser hardware.

Then, I saw Microcenter begin selling refurbished RTX 3090 24GB Founder Edition video cards. While these cards are three years old and used, they sell for 1/5 the price of an A6000 and have nearly identical specifications to the A6000 except for having only half the VRAM. I thought it would be slightly better than plodding along with the 4060 Ti, so I decided to list that card on eBay and apply the money from its sale to the price of a 3090.

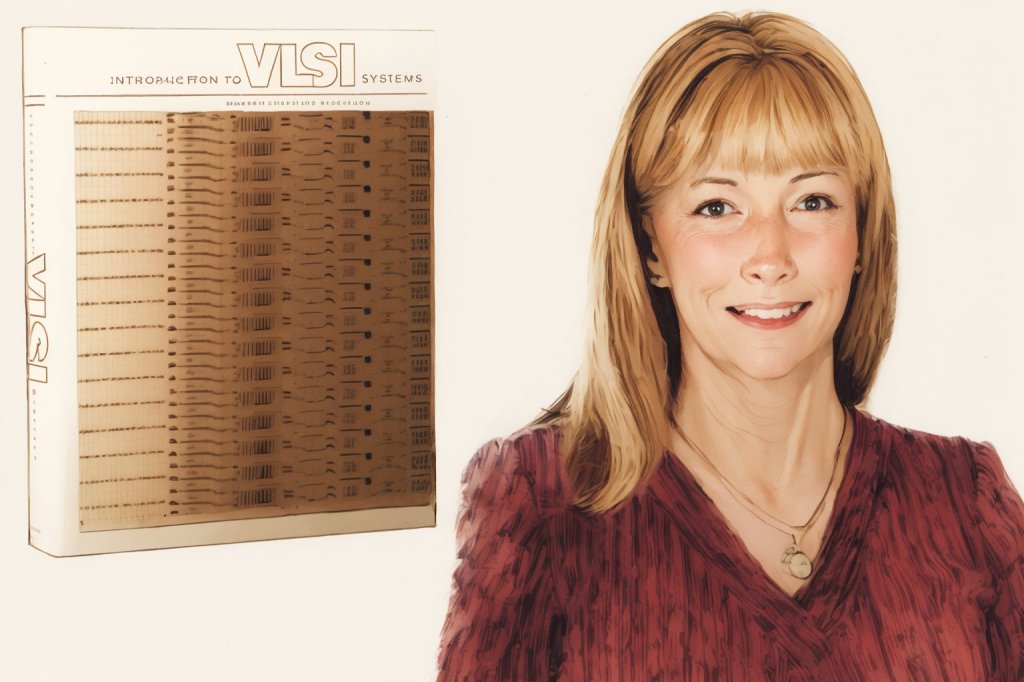

As you can see above, the 3090 is a massive video card–occupying three slots as opposed to only two slots by the 3070, A6000, and 4060 Ti shown below.

The next hardware investment that I plan to make is meant to increase the bandwidth of my system memory. The thing about generative AI–particularly text generative AI–is the need for lots of memory and more memory bandwidth. I currently have dual-channel DDR4-3200 memory (51.2 GB/s bandwidth). If I upgrade to a dual-channel DDR5 system, the bandwidth will increase to a theoretical maximum of 102.4 GB/s. Another option is to go with a server/workstation with a Xeon or Threadripper Pro that supports 8-channel DDR4 memory, which would yield a bandwidth of 204.8 GB/s. Each doubling of bandwidth roughly translates to doubling how many tokens (the constituent word/letter/punctuation components that generative AI systems piece together to create sentences, paragraphs, etc.) are output by a text generative AI using CPU + GPU inference (e.g., llama.cpp). If I keep watching for sales, I can piece together a DDR5 system with new hardware, but if I want to go with an eight-channel memory system, I will have to purchase the hardware used on eBay. I’m able to get work done so I will keep weighing my options and keep an eye out for a good deal.