Hall, Donald E. The Academic Self: An Owner’s Manual. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2002. Print.

I picked up Donald E. Hall’s The Academic Self from the Georgia Tech Library after completing my teaching assignment for Spring 2013–eleven years after the book had been published. Specifically, I was looking for books and articles to help me grapple with the challenges of this stage of my professional life as a postdoctoral fellow: teaching a 3-3 load, performing service duties, researching, writing, receiving rejections (and the far less often acceptance), and applying for permanent positions. In the following, I summarize Hall’s arguments, provide some commentary, and close with a contextualized recommendation.

Hall states in the introduction that the goal of The Academic Self is, “encourage its readership to engage critically their professional self-identities, processes, values, and definitions of success” (Hall xv). I found this book to be particularly useful for thinking through my professional self-identity. As I was taught by Brian Huot at Kent State University to be a reflective practitioner in my teaching and pedagogy, Hall argues for something akin to this in terms of Anthony Giddens’ “the reflexive construction of self-identity” (qtd. in Hall 3). Hall truncates this to be “self-reflexivity,” or the recognition that who we are is an unfolding and emergent project. I use this blog as part of my processes of self-reflection–thinking through my research and teaching while striving to improve both through conscious planning and effort.

However, unlike the past where the self was static and enforced by external forces, modernity (and postmodernity–a term Hall, like Giddens, disagrees with) has ushered in an era where the self is constructed by the individual reflectively. From his viewpoint, the self is a text that changes and can be changed by the individual with a greater deal of agency than perhaps possible in the past (he acknowledges his privileged position earlier in the book, but it bears repeating that this level of agency certainly is not equally distributed).

In the first chapter, titled “Self,” Hall writes, “Living in the late-modern age, in a social milieu already thoroughly pervaded by forms of self-reflexivity, and trained as critical readers, we academics in particular have the capacity and the professional skills to live with a critical (self-) consciousness, to reflect critically upon self-reflexivity, and to use always our professional talents to integrate our theories and our practices” (Hall 5). If we consider ourselves, the profession, and our institutions as texts to be read, we can apply our training to better understanding these texts and devise ways of making positive change to these texts.

He identifies what he sees as two extremes that “continue to plague academic existence: that of Casaubonic paralysis and Carlylean workaholism” (Hall 8). In the former, academics can be caught in a ignorant paranoia like Casaubon of George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871-1872), or in the latter, academics can follow Thomas Carlyle’s call to work and avoid the “symptom” of “self-contemplation” (qtd. in Hall 6).

In the chapter titled “Profession,” Hall calls for us to apply our training to reflective analysis and problem solving of our professional selves and our relationship to the ever changing state of the profession itself. He questions to what extent the work of professionalism (seminars, workshops, etc.) are descriptive or prescriptive. “The ideal of intellectual work” varies from person to person, but it is an important choice that we each must make in defining who we are within the profession.

He reminds us that, “much of the pleasure of planning, processing, and time management lies not in their end products–publication or project completion–it is derived from the nourishment –intellectual, communal, and professional–provided by the processes themselves” (Hall 46). He builds his approach to process on his personal experiences: “Unlike some, I know well when my work day is over. Part of the textuality of process is its beginning, middle, and most importantly, its end” (Hall 46).

His talking points on process are perhaps the most practical advice that he provides in the book. In planning, he advises:

- begin from the unmovable to the tentative in your scheduling, know yourself–plan according to your habits and work on those aspects of your planning that need adjustment, and stick to your well planned schedule to yield the personal time that you might be lacking now without such a plan

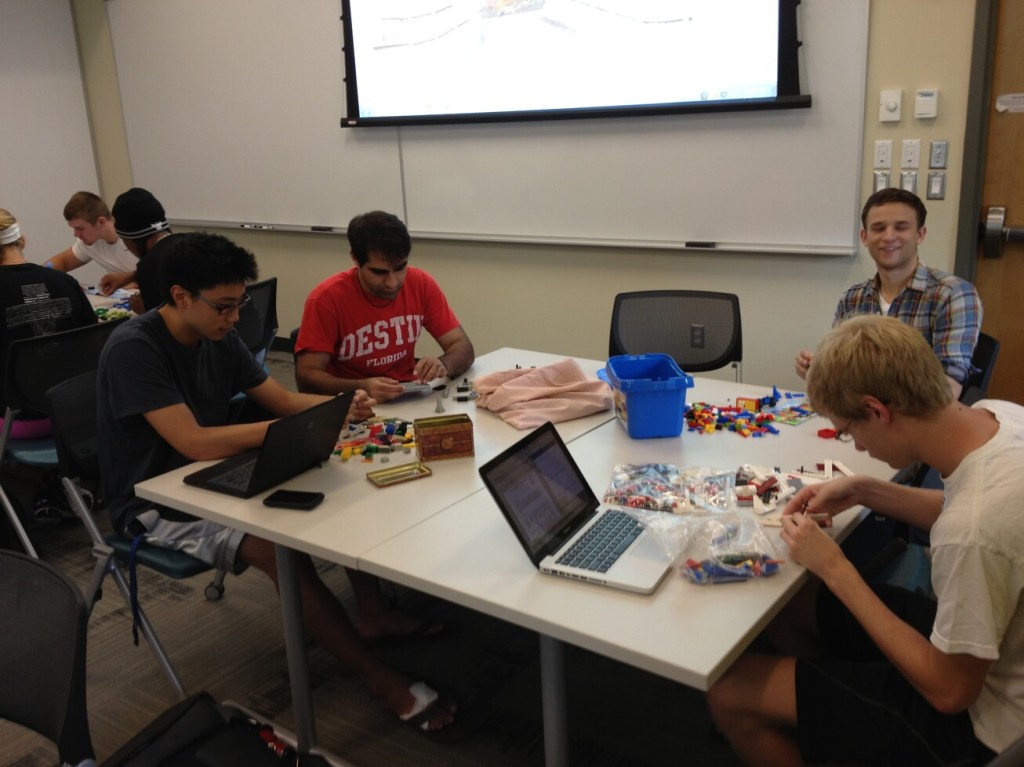

- break goals and deliverables into their constituent parts [or building blocks (my Lego analogy) or code (my programming analogy)]

- monitor your progress and see daily/smaller goals as ends in themselves rather than simply means to a greater end

- take ownership of your goals, schedule, and commitments to others [this is something that I carry forward from my Mindspring days: Core Values and Beliefs: Do not drop the ball.]

- deal with and learn from setbacks–life, bad reviews, rejections, etc. [this is easier said than done, and the external effects of bad reviews goes beyond its effect on the writer]

- let change happen to our goals and research as our workplace, interests, and circumstances change

- taking ownership of our work in these ways can help protect us from and strengthen us against burnout

Hall goes on to suggest ten steps for professional invigoration to help folks suffering from a stalled career or burnout. However, these ten pieces of advice are equally applicable to graduate students, postdocs, and beginning faculty: join your field’s national organization, read widely in your field, set precise goals, maintain a daily writing schedule [my most difficult challenge], present conference papers, write shorter artifacts to support your research [reviews or my case, this blog], know the process and timeline of manuscript publishing, foster relationships with publishers and editors, politely disengage from poor or dysfunctional professional relationship/praise and value positive relationships, and find support in your local networks.

The final chapter, “Collegiality, Community, and Change,” reminds us, “always t put and keep our own house in order” (Hall 70). He suggests strategies counter to what he calls “the destructive ethos of ‘free agency’ that seems to pervade the academy today–the mindset that institutional affiliations are always only temporary and that individuals owe little to their departments or institutions beyond the very short term” (Hall 70). On professional attitudes, he encourages a focus on the local (institution) before national (beyond the institution), the current job as potentially your last job–treat it with that respect, meet institutional expectations, collegial respect of others, and learning the history of our institution/school/department from everyone with whom we work.

Perhaps most notably, he writes, “If we measure our success through the articulation and meeting of our own goals, as I suggest throughout this book, we can achieve them without begrudging others their own successes. However, if we need to succeed primarily in comparison to others, then we are deciding to enter a dynamic of competition that has numerous pernicious consequences, personal and inter-personal” (Hall 74-75). As I have written about on Dynamic Subspace before, it was the overwhelming in-your-faceness of others’ successes on social media like Facebook that distracted me from my own work. Seeing so many diverse projects, publications, and other accomplishments made me question my own works-in-progress before they had time to properly incubate and grow. For all of social media’s useful and positive aspects for maintaining and growing networks of interpersonal relationships, I had the most trouble resisting the self-doubt that the Facebook News Feed generated for me.

Finally, he encourages dynamic and invested change in departments and institutions. However, as junior faculty, it is important to research and weigh the possible repercussions for working to make change. Hall is not arguing against change by those without tenure, but he is warning us to proceed cautiously and knowledgeably due to a number factors: potential sources of resistance, jeopardizing our jobs, etc.

Hall’s “Postscript” reinforces the overarching idea of ownership by calling on the reader to live with “intensity,” an idea that inspired Hall from Walter Pater’s 1868 The Renaissance: “burn always with [a] hard, gem-like flame” (qtd. in Hall 89). Hall’s intensity is one self-motivated, well-planned, dynamically agile, and passionately executed.

Hall’s The Academic Self is a very short read that is well worth the brief time that it will take to read. It offers some solid advice woven with the same theoretically infused self-reflexivity that he encourages. It practices what it preaches. The main thing to remember is that the book is eleven years old. When it was published, the field of English studies was experiencing an employment downturn (albeit one not as pronounced as in recent years). Michael Berube’s “Presidential Address 2013–How We Got Here” (PMLA 128.3 May 2013: 530-541), among many other places–this issue just arrived in the mail today, so I was reading it between chapters of Hall’s book, picks up some of the other challenges that graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and junior faculty have to contend with in the larger spheres of the profession and society. The other advice that Hall provides on personal ownership and collegiality, I believe, remains useful and inspirational. In addition to reading Hall’s book, you should check out his bibliography for further important reading in this vein.