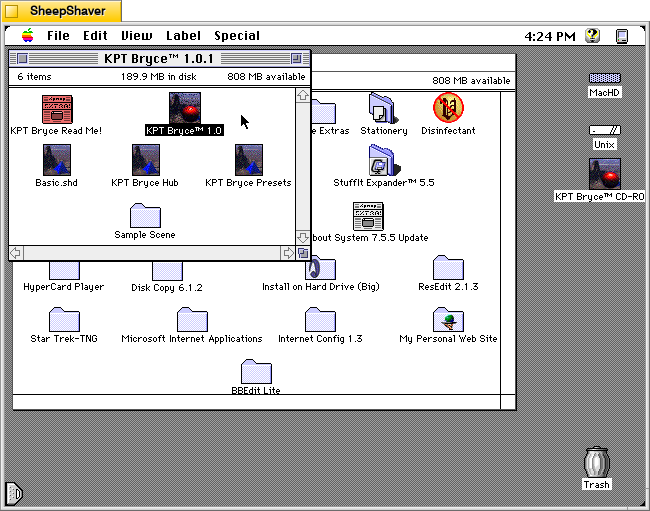

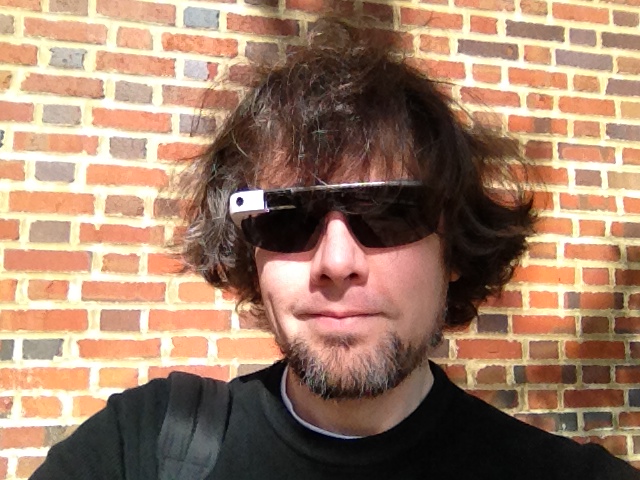

When Google Glass debuted, I thought it was a cool piece of tech. Recording POV video and photos for my maker-oriented work and getting updates unobtrusively in class, meetings, and conferences were its main selling points to me. I wrote about some of my experiments with Google Glass and LEGO here. Unfortunately, it had its hardware and software limitations. One person who I interacted with took extreme umbrage with it. And, Google’s waning support over the years didn’t help either. Eventually, I sold it on eBay as I had stopped using it altogether.

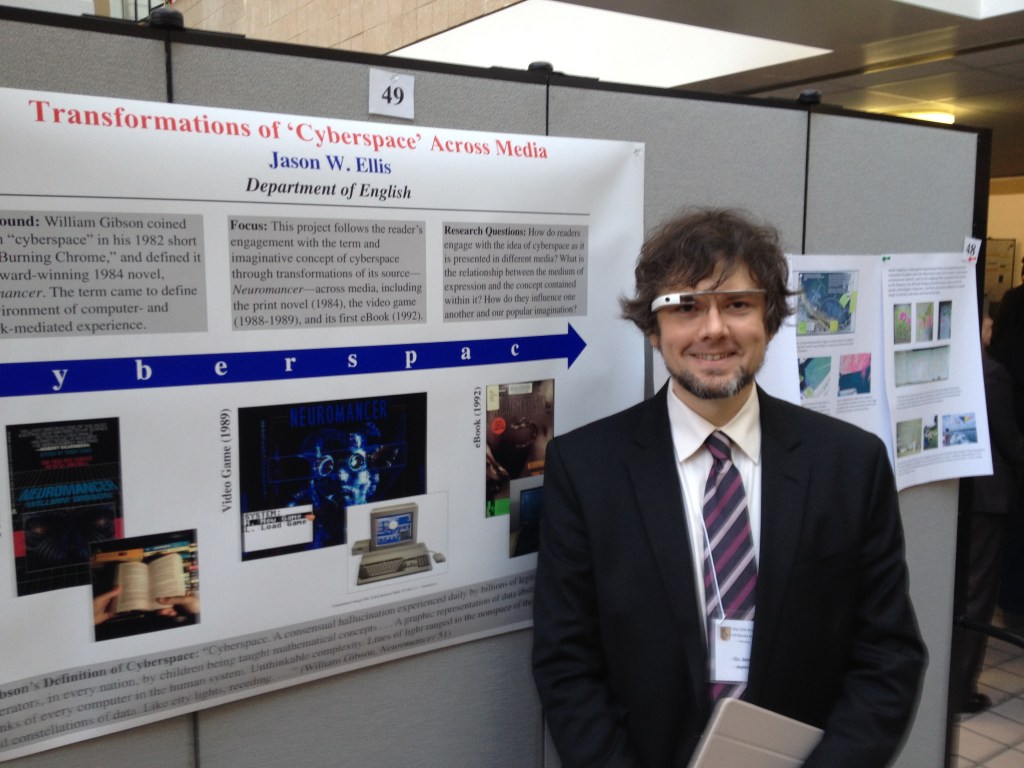

Use in Professional Settings

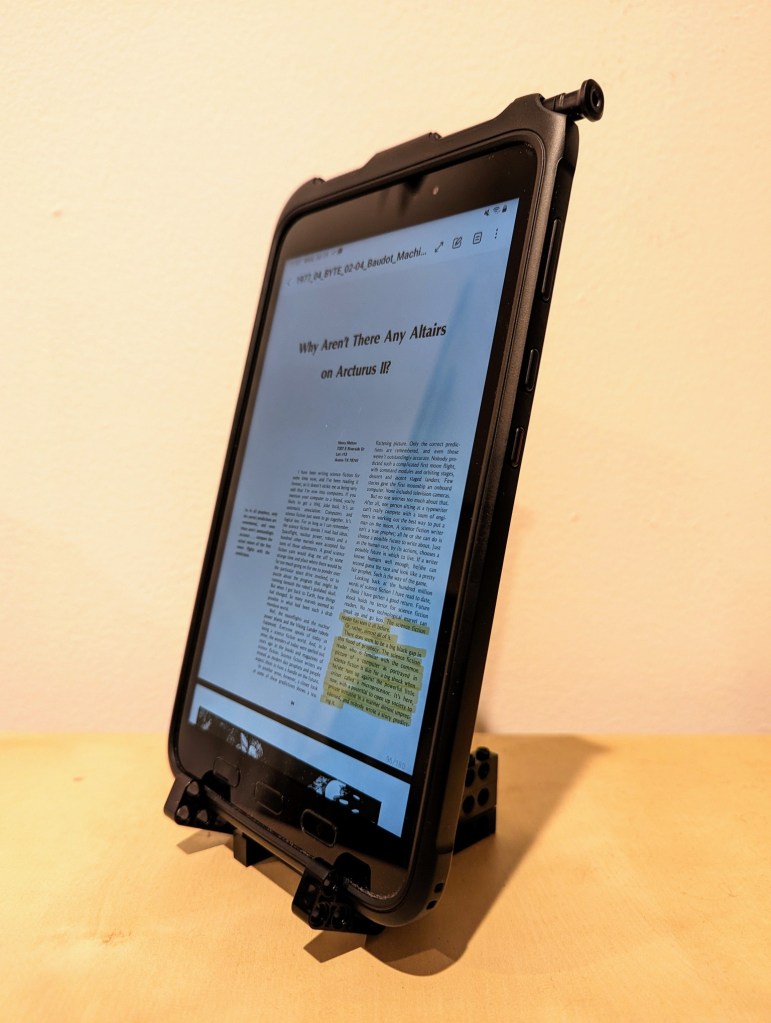

When giving presentations that related to interfaces and new media, I often wore Google Glass as a prop, which I would reference in my talk. Had I been very clever, I would have used it like a teleprompter, but it was often easier to read from notes printed or on a tablet in hand.

I did get told off by someone who I didn’t know shortly before my co-presentation with Wendy Hagenmaier on “Digital Archives and Vintage Computing at Georgia Tech” at the Southeast Vintage Computer Festival 2.0 in Roswell, GA on 4 May 2014. I don’t know who she was, but she zeroed in the Glass, got perilously in my face, waved her hand dangerously close to my face and the Glass, and demanded that I stop recording video of her. I stepped backward and tried to explain that it wasn’t recording video or taking photos–I only had it conveying messages from my phone at the time. The thing about the Glass is that the computing unit got very, very hot–uncomfortably hot–if you recorded video for more than a minute or two. Of course, it would eat through its battery, too. So, full time recording wasn’t really possible. It did have a beta feature to take a photo when you blinked, but I never left the feature on as it resulted in lots of useless photos and depleted the battery. She was pissed and was having none of my explanation. Since we weren’t really having a discussion, I just said that I was sorry and walk away. It was an unnerving encounter since she was walking around with the organizer who remained silent during the exchange. Perhaps it had more to do with it being a Google product? What about it being a public space? What about the many other participants carrying smartphones with cameras as well as dedicated point-and-shoot and DSLR cameras? Perhaps she gained her intended effect as I was more cautious about where and when I wore them.

For such an encounter, it would have been nice if the Glass had a built-in lens cover that lets others around the Glass wearer know at a glance if the lens was exposed or not, or if the camera part could have been modular in some way so that the wearer could have the AR but remove the camera when it wasn’t needed.

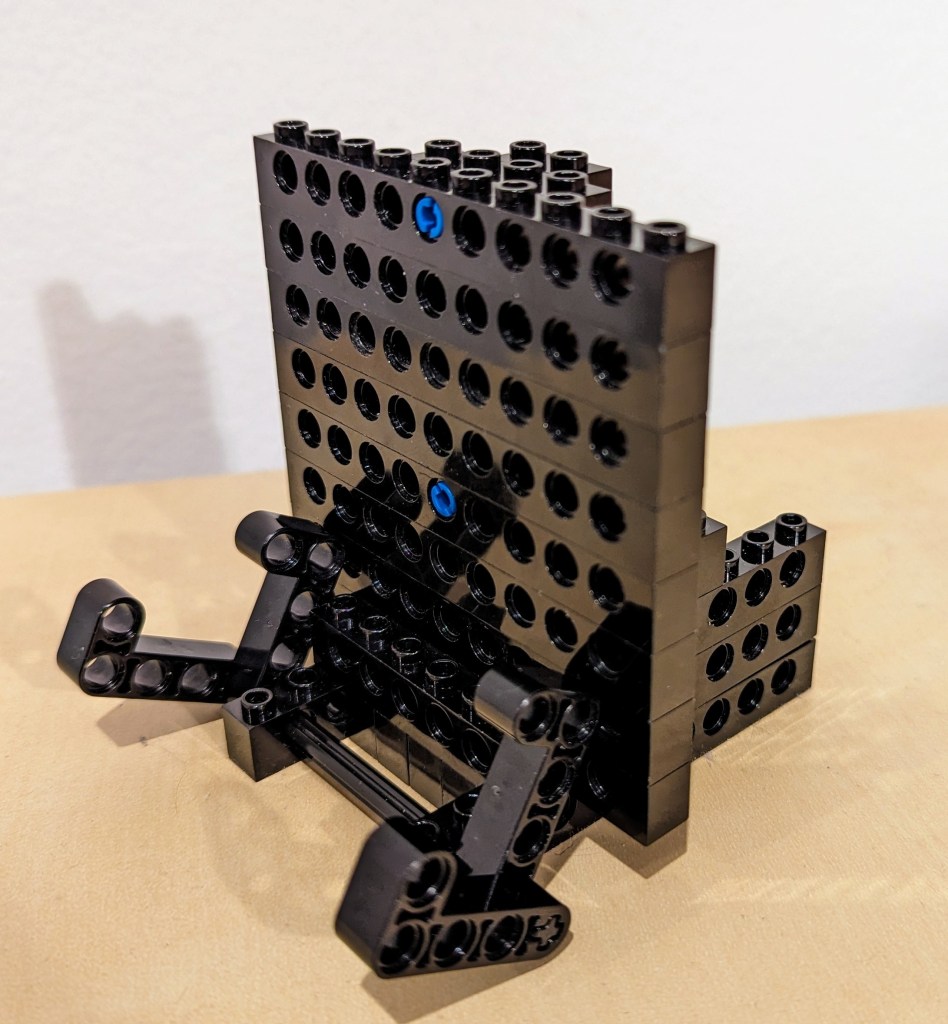

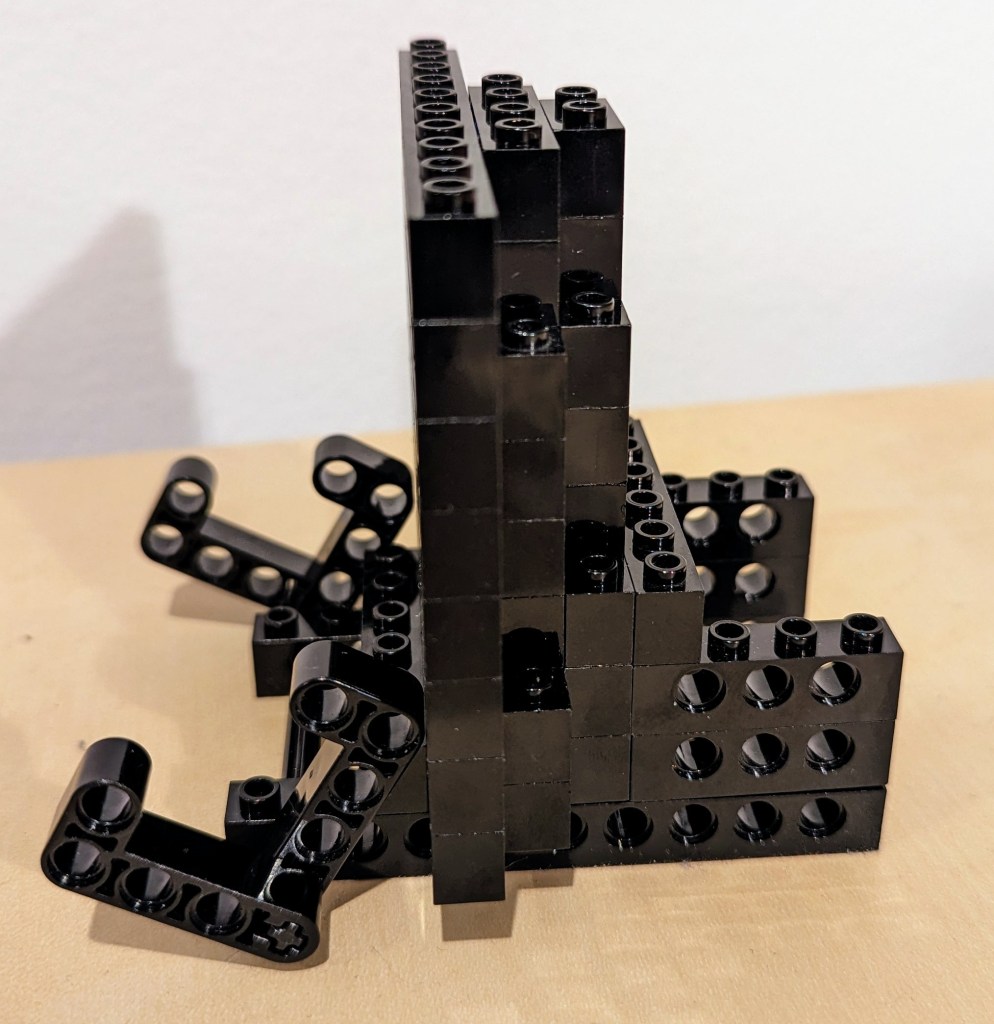

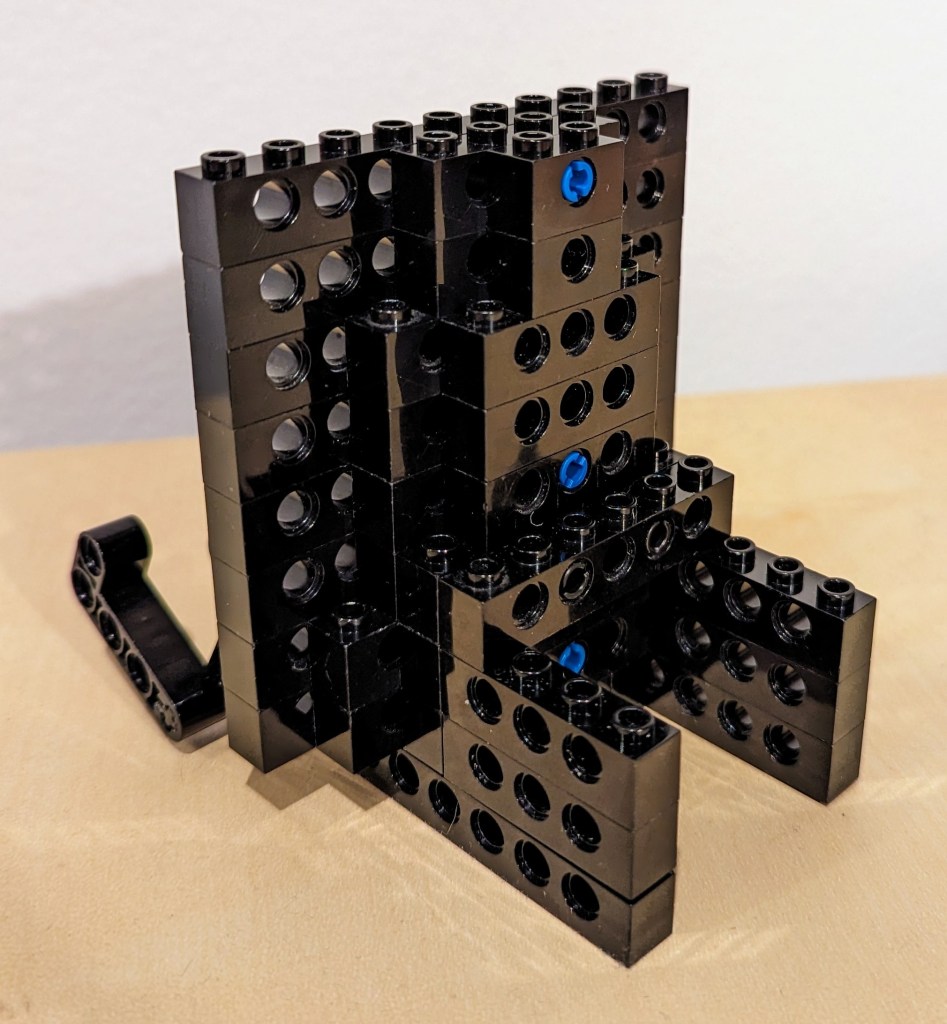

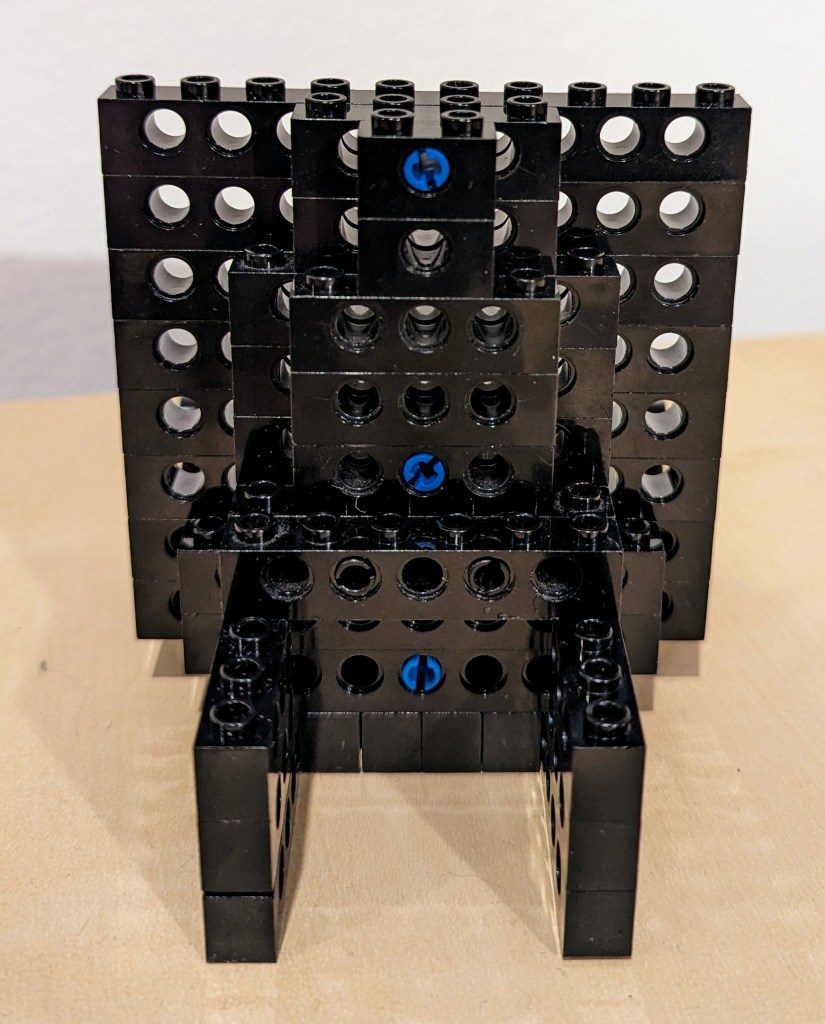

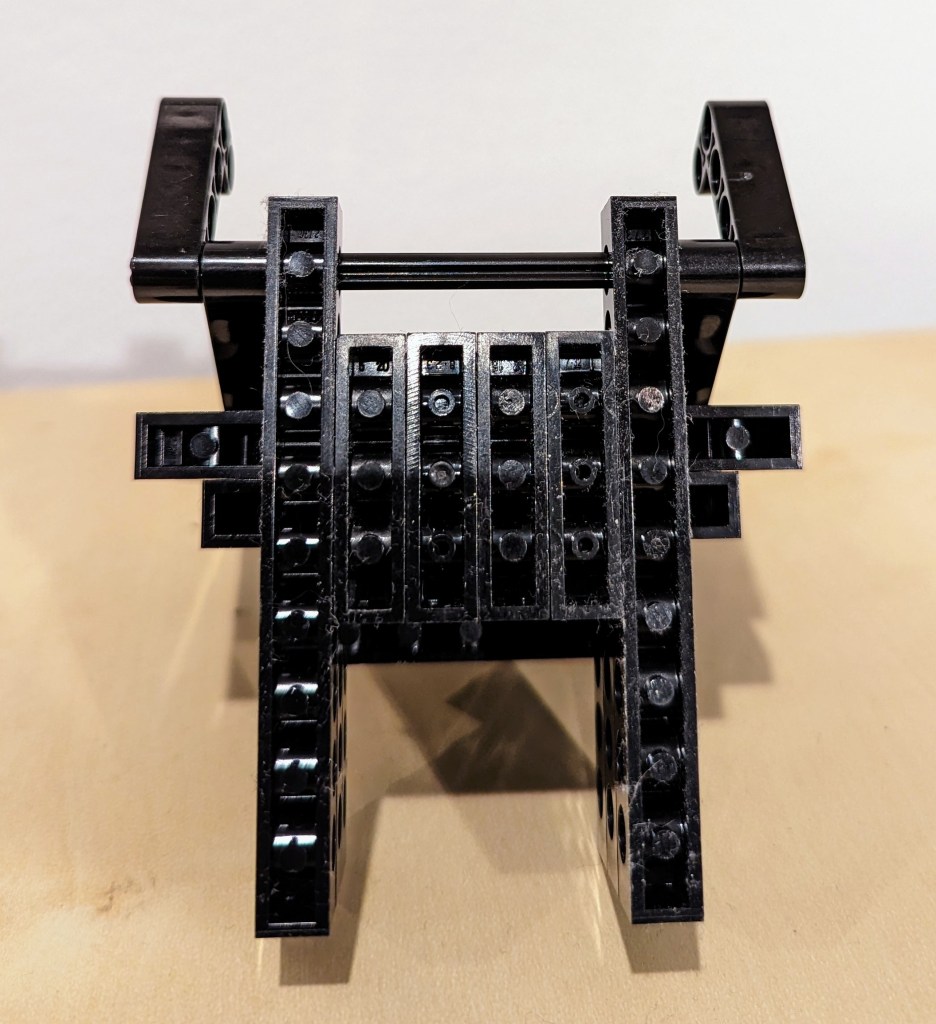

Google Glass Kit

I opted for the Google Glass Explorer kit that included detachable sunglasses. The kit included a single ear speaker that connected to the computing unit on the right side. An AC charger, USB cable, and felt carrying cases for the Glass and sunglasses were included, too.

Before Its Time?

Wearable technology like this seems inevitable. Good hardware and software design combined with killer apps/features would make this an invaluable tool, I think. The battery life and heat problems were downplayed during the initial public release, but they were real problems that robbed Glass of the bare minimum of functionality that it deserved. Had Google cracked those two issues, the software could have been developed further on a stable hardware platform.

The lack of apps, poor battery life, heat production, and trouble with the voice activated features made me decide to resell it. Thankfully, I was able to recoup most of the cost when I sold it a year later.

There seems to be steady interests in AR. Microsoft’s Hololens is neat, but it isn’t something that you can wear around all day. Apple’s upcoming Vision Pro looks cool, too, but it will be something aimed for specific use cases and not be a wearable augmentation to our daily, digital interaction with the world like Glass. Snap’s next generation of Spectacles seems like a high-tech version of Glass with full vision overlay, but it might be too opaque for all day and indoor use. Will something else come along to fulfill the promise of Glass?