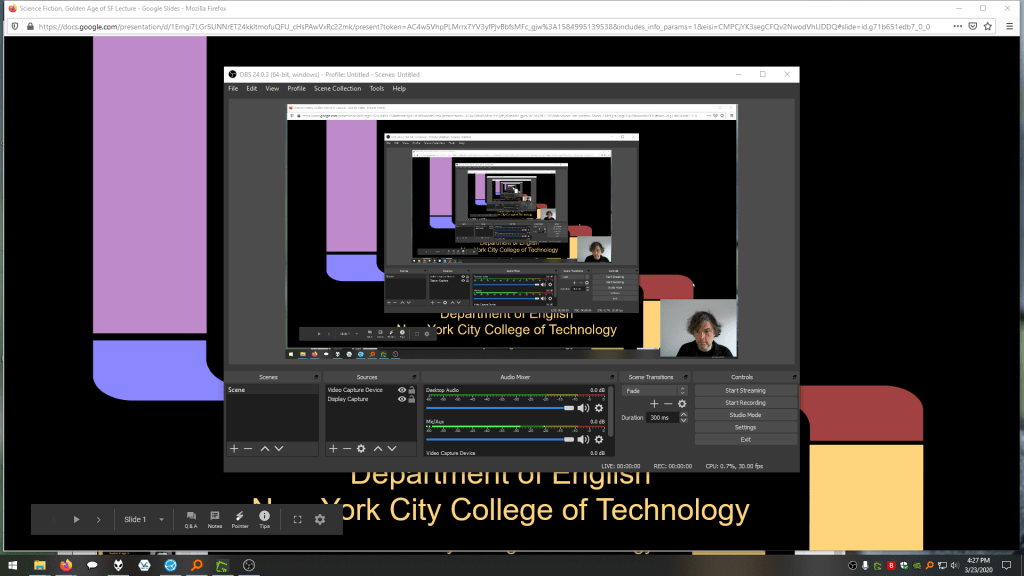

An anthropomorphic cat taking notes in a lecture hall. Image created with Stable Diffusion.

I tell my students that I don’t ask them to do anything that I haven’t done or will do myself. A case in point is using the summer months for a learning boost. LinkedIn Learning offers new users a free trial month, which I’m taking advantage of right now.

While I’ve recommended students to use LinkedIn Learning for free via the NYPL, completion certificates for courses don’t include your name and they can only be downloaded as PDFs, meaning you can’t easily link course completion to your LinkedIn Profile. Due to the constraints with how library patron access to LinkedIn Learning works, I opted to try out the paid subscription so that it links to my LinkedIn Profile. However, I wouldn’t let these limitations hold you back from using LinkedIn Learning via the NYPL if that is the best option for you–just be aware that you need to download your certificates and plan how to record your efforts on your LinkedIn Profile, your resume, and professional portfolio.

After a week of studying, I’ve earned certificates for completing Introduction to Responsible AI Algorithm Design, Introduction to Prompt Engineering for Generative AI, AI Accountability Essential Training. And, I passed the exam for the Career Essentials in Generative AI by Microsoft and LinkedIn Learning Path. I am currently working on the Responsible AI Foundations Learning Path. These courses support the experimentation that I am conducting with generative AI (I will write more about this soon), the research that I am doing into using AI pedagogically and documenting on my generative AI bibliography, and thinking how to use AI as a pedagogical tool in a responsible manner.

For those new to online learning, I would make the following recommendations for learning success:

- Simulate a classroom environment for your learning. This means find a quiet space to watch the lectures while you are watching them. Don’t listen to music. Turn off your phone’s notifications. LinkedIn courses are densely packed with tons of information. Getting distracted for a second can mean you miss out on something vital to the overall lesson.

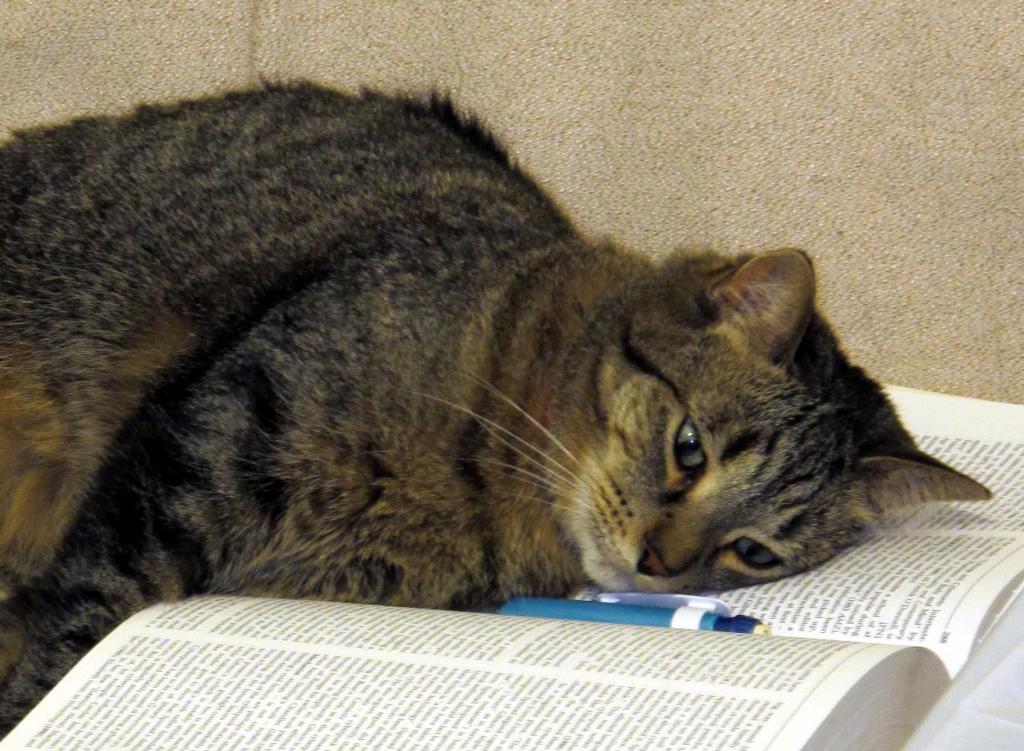

- Have a notebook and pen to take notes. While watching the course, pause it to write down keywords, sketch charts, and commit other important information to your notes. The act of writing notes by hand has been shown to improve your memory and recall of learned information. Don’t keep notes by typing as this is less information rich learning than writing your notes by hand.

- Even though a course lists X hours and minutes to completion, you should budget at least 50% more time in addition to that time for note taking, studying, quizzes, and exams (for those courses that have them).

- While not all courses require you to complete quizzes and exams for a completion certificate, you should still take all of the included quizzes and exams. Research shows that challenging ourselves to recall and apply what we’ve learned via a test helps us remember that information better.

- After completing a course, you should add the course certificate to your LinkedIn Profile, post about completing the course (others will give you encouragement and your success might encourage others to learn from the same course that you just completed), add the course certificate to your resume, and think about how you can apply what you’ve learned to further integrate your learning into your professional identity. On this last point, you want to apply what you’ve learned in order to demonstrate your mastery over the material as well as to fully integrate what you’ve learned into your mind and professional practices. This also serves to show others–managers, colleagues, and hiring personnel–that you know the material and can use it to solve problems. For example, you might write a blog post that connects what you’ve learned to other things that you know, or you might revise a project in your portfolio based on what you’ve learned.

- Bring what you’ve learned into your classes (if you’re still working toward your degree) and your professional work (part-time job, internship, full-time job, etc.). Learning matters most when you can use what you’ve learned to make things, solve problems, fulfill professional responsibilities, and help others.