On Thursday, 9/19/19, the OpenLab, which I joined as a Co-Director this academic year, is hosting an Open Pedagogy event on “Beyond the ADA” at City Tech in the Faculty Commons at 4:30pm. We will lead a discussion about issues of access, including those related to disabilities, while looking beyond compliance to dynamic, inclusive, and supportive pedagogies that enrich learning for all students. OpenLab’s theme for this academic year is “Access.”

While reading through the suggested texts informing the background of our discussion, I reflected on my personal, workplace, and classroom experiences relating to access.

My first memory of disabilities relates to my Uncle Pat. After returning from Vietnam, he started a family in Walnut Grove, Alabama and worked for the railroad. While at work cutting an in-service rail, another truck accidentally bumped his truck, which ran over him and left him a quadriplegic. On visits, I saw first hand how he overcame him disability through mobility with a puffer-controlled electric wheelchair, but the constraints of 24-hour nursing care and accessible buildings were also obviously apparent. Nevertheless, he always trounced me at chess–I just had to setup the board and move the pieces.

In my hometown, Emory Dawson was another quadriplegic that I knew through Boy Scouts. His injury originated from the Vietnam War and he had some shoulder mobility, which enabled him to drive his own van with the aid of a suicide knob and special controls for brake, throttle, and shifting. In addition to Scouts, Mr. Dawson was involved in many social groups and charities, and he led an active life to support them. I don’t know if it was *the* factor in its construction, but a fellow Scout took on the building of a concrete wheel chair ramp for a rank-level project at Troop 224’s hut in the back of Lakeside United Methodist Church on 341 Highway and Mr. Dawson visited our meetings on occasion.

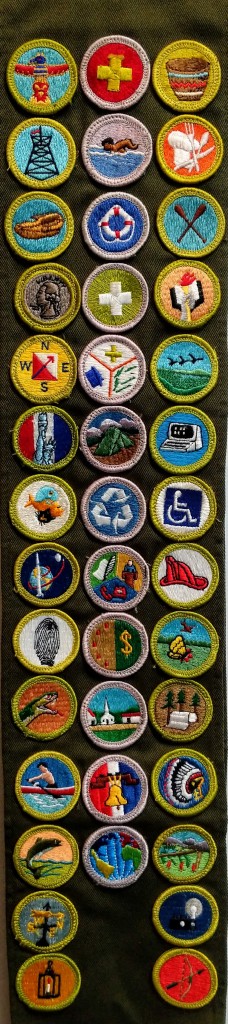

It was during that time that I earned my Handicap Awareness merit badge on Feb. 5, 1990, which you can see on the seventh row of the image above of my Boy Scout merit badge sash with the International Symbol of Access surrounded by a green circle. The requirements of the merit badge focused on learning about disabilities and gaining an empathetic awareness of disabilities through simulated impairments of hearing, sight, manual, and mobility. Less visible disabilities were outside the scope of that component of the merit badge’s requirements, but they could be reintroduced through the learning and outreach components (but this was not, as I remember, something that I was cognizant of at that time).

I wondered how the merit badge might have changed since I earned it, and I’m glad to report that it had changed for the better, I think. In 1993, the merit badge was renamed as Disabilities Awareness, and its requirements shifted from personal simulation of physical impairments to learning first hand from others’ lived experience, identifying accessibility issues in the community, and performing advocacy for better accessibility. There was an advocacy element to Handicap Awareness (publicly sharing what you’ve learned with others), but Disabilities Awareness foregrounds this in a more integrated fashion. It would be interesting to read the merit badge series handbooks for the former and latter versions of this merit badge, but I only have access to the requirements while writing this blog post.

When I worked in Technical Support at Mindspring Internet in Atlanta, Georgia, I was tasked with working with the Deaf and Hard of Hearing via a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD). With a single line of LCD text and a running paper tape, I communicated with deaf customers to solve their technical support issues. Unfortunately, many customers had their TDD in a different room, different floor, different part of the house, than their computer. This introduced a tremendous lag between what I wrote questioning or instructing and their response following a result. Also, I was given this extra task to supplement my lower-than-expected phone support numbers (It’s my understanding that Mike McQuary pushed raw number of support calls over the quality of calls and successful resolution of customer issues–valuing quantitative measures over the qualitative effects of those measures on customers and employees). So, I was on the phone with one customer and on the TDD with another customer. Over time, I got better at switching my attention between customers, but more often than not, the customers on the TDD got the short end of the stick as my phone call numbers were given priority by management (QA Brian: “You’ve got to take more calls or you’ll get fired.”). It was an unfair situation for the deaf and hard of hearing customers.

When I began teaching, I worked with a student on the autistic spectrum. This was a challenging situation for the student as the reported accommodations couldn’t support their success in the classroom, and I took it on myself to provide additional support to help the student progress in the course. I was advised that there was only so much that I could do to support the student, and I should have, in retrospect, dialed back my professional involvement. Nevertheless, this student did help me recognize another side of student needs and the impediments to access that students on the spectrum encounter. I have adjusted my syllabi to be more accommodating to students–self-reporting or not–through multiple activities and assignment adjustments on a one-by-one basis (as long as course learning outcomes are always met).

Another student had a severe vision impairment and had reported accommodations, including a phone with magnifying app for reading text and a student volunteer note-taker. While the classroom and supporting material could be adjusted to support the student when present, outside life prevented the student from attending some classes. This led to testy encounters between myself and the note taker, who felt their time being wasted, and follow-up conversations between myself and the student to facilitate peace between the student and note taker so that support would be maintained. Of course, life outside of school was creating a different kind of access problem for this student–getting to campus was a hurdle in part due to the student’s vision problem and the issues that can come up in one’s personal life that lead to problems, such as not having someone to help you navigate from home to campus.

I’ve come to realize that there are things that I can do to help as an instructor–those things that I have control over, such as pedagogy, syllabi, assignments, activities, and one-on-one support, and there are many other things outside the classroom that I don’t have control over. Also, the Open Pedagogy event conversation and the work that we can do together to increase access and lower barriers–in the classroom, online, on campus, and in our lived world–for students and faculty with disabilities is something that we must endeavor to accomplish.

In addition to the informative readings OpenLab Digital Pedagogy Fellow Jesse Rice-Evans assembled for the Open Pedagogy event, I found these additional readings useful for my thinking:

Adams, Rachel, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin. “Disability.” Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, NYU Press, 2015, 5-12.

Campbell, Kumari. “Ability.” Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, NYU Press, 2015, 12-14.

Mullaney, Clare. “Disability Studies: Foundations & Key Concepts.” JSTOR Daily, 13 April 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/reading-list-disability-studies/. Accessed 18 Sept. 2019.

Williamson, Bess. “Access.” Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, NYU Press, 2015, 14-16.