This is the twentieth post in a series that I call, “Recovered Writing.” I am going through my personal archive of undergraduate and graduate school writing, recovering those essays I consider interesting but that I am unlikely to revise for traditional publication, and posting those essays as-is on my blog in the hope of engaging others with these ideas that played a formative role in my development as a scholar and teacher. Because this and the other essays in the Recovered Writing series are posted as-is and edited only for web-readability, I hope that readers will accept them for what they are–undergraduate and graduate school essays conveying varying degrees of argumentation, rigor, idea development, and research. Furthermore, I dislike the idea of these essays languishing in a digital tomb, so I offer them here to excite your curiosity and encourage your conversation.

This is a milestone Recovered Writing post. I build on the ideas that I explored in my undergraduate thesis at Georgia Tech (which you can read here): Cold War identities, authenticity, humanity, machines, and artificial intelligence. Later, at Kent State University, I took only one nugget from these ideas to further explore human and machine experiences through neuroscience and the cognitive sciences.

To develop my MA dissertation, Dr. David Seed agreed to work with me on my project. We would meet in his office every few weeks. We would talk about my project and he would assign me readings and books that we would then discuss in further detail at our next meeting. The process of working with Dr. Seed–meetings, discussions, writing, revising, and further discussions–was intellectually exciting and incredibly productive. The intensity of the work due to the constraints of time and moving back to the United States to begin the PhD program at Kent State University added impetus to its eventual completion during the Summer 2007. I consider myself very fortunate to have worked with Dr. Seed on this project and I am glad to share my research here on my blog.

Below, I am including my dissertation’s abstract, research questions, and the dissertation itself. My dissertation is 16,376 words long including Works Cited list and end notes. If you take the time to read it all or in part, please drop me a line (contact info to the right) or leave a comment.

——————-

Abstract

Jason W. Ellis

Post-Cold War American Identities in Battlestar Galactica

In this dissertation, Ellis argues that there is a shift in SF to more directly engage contemporary issues, and I describe how the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica goes further than its 1978 source material in this regard. He approaches this shift from several different yet interrelated vectors including an analysis of the enemy-other Cylon threat and its destabilization of Western democratic identity, which reflects the reboot of Tom Engelhardt’s cycle of American triumphalism following the Second World War. He analyzes the portrayal of human and alien/enemy-other identities in the two BSG series and the development of human and Cylon identities across time and the way in which they begin to blur and merge in the re-imagined series. This involves analyzing identities in each series separately and then exploring the way those identities are in dialog with the other series as well as culture at large. Then, he uses those conclusions to answer if and to what extent there is an identity shift in SF from the Cold War to the Post-Cold War era and how that shift is connected to and represents cultural and historical developments.

——————-

Research Questions (note the earlier title for the project)

Jason W. Ellis

Mr. Andy Sawyer and Dr. David Seed

ENG 602: Dissertation

Spring 2007

Dissertation Planning: Subversion of the Self in the Re-Imagined Battlestar Galactica

General Questions

Does SF change following the end of the Cold War? Is Post 9/11 SF significantly or subtly different than Cold War SF? How is personal identity dealt with in Cold War SF? What differences are there between identity for the good guys versus the bad guys?

Specific Questions

Does the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica (BSG) represent a shift in SF from a Cold War mode to a new, Post 9/11 mode? How is identity portrayed differently in the Post 9/11 re-imagined BSG than in the Cold War era original BSG? How are enemy identities portrayed in these two series? Are there significant differences between the two series, or is the new BSG merely a continuation of Cold War narrative?

Methodology

Using the re-imagined BSG as a test case, I want to answer the question: Does the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica represent a shift in SF from a Cold War mode to a new, Post 9/11 mode? BSG is a unique example to study, because it’s original “text” comes from the Glen A. Larson 1978 movie and subsequent ABC television series, which is deeply embedded within the Cold War temporally as well as narratively. The new BSG, even with Larson attached as a “consulting producer,” is a very different story than the original. Whereas the original BSG presents simplified characters in a dualistic struggle between humanity and machine mapped over the Cold War ideologies of West/democracy and East/communism, the new BSG is a loosely veiled retelling of the conflict in Iraq and the Global War on Terrorism. However, the new BSG also relies on Cold War narrative influences such as those pointed out by Tom Engelhardt in The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation. For example, both series rely on the sneak attack on democracy that was born out of World War II with the Nazi blitzkrieg and their disregard for non-aggression pacts, and more specifically, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In BSG, humanity is attacked by Cylon/machine invaders–during a peace conference in the original series and during years of cease fire in the re-imagining. Additionally, Engelhardt makes a connection between the merging of self and the enemy following the use of atomic bombs at the end of WWII:

The atomic bomb that leveled Hiroshima also blasted openings into a netherworld of consciousness where victory and defeat, enemy and self, threatened to merge. Shadowed by the bomb, victory became conceivable only under the most limited of conditions, and an enemy too diffuse to be comfortably located beyond national borders had to be confronted in an un-American spirit of doubt (6).

The original BSG follows this trajectory in part, because the machine Cylons resemble humanity, and in the latter part of the series, they develop uncanny human Cylons. However, the re-imagined BSG literally takes this much further by merging the “enemy and self” with the human doppelganger Cylon clones (“skinjobs”). Additionally, the overwhelming odds of the Cylon forces to humanity’s approximately 48,000 survivors reinforces the Cold War framework of overcoming staggering odds following the treacherous sneak attack.

Where the new BSG differs from the original specifically has to do with self and enemy identities. Characters in the new BSG are much more developed and are decidedly not archetypes as in the original series. Also, the human appearing Cylons have their own motivations and characteristics that place them above the status as targets as in much other SF. However, the truly interesting element of the new BSG is the fact that identities of both humans and Cylons is that they are both dealing with an identity crisis. Humans worry that they may be sleeper Cylons acting out their lives, unknowing about their “true” selves until the signal or time lapse occurs to activate their hidden programming. The Cylons are worried about internal dissention and individualistic concerns that run counter to the anarchistic commune ideology promoted by group consensus. Also, there is the threat of the final five Cylons, five unknown human-like Cylons hidden amongst humanity. Who are these Cylons, and what will their presence mean for the existing Cylons? Other identity issues that concern both humans and Cylons are psychological issues with the human Gaius Baltar and the Cylon “Caprica Six.”

I will utilize the original BSG and re-imagined BSG series as primary sources, but I will also refer to ancillary materials such as DVD extras as well as sourcebooks and official guides. Several useful secondary critical sources are Englehardt’s The End of Victory Culture, Scott Bukatman’s Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction, David Seed’s American Science Fiction and the Cold War, and J.P. Telotte’s Replications.

——————-

Dissertation

Jason W. Ellis

Mr. Andy Sawyer and Dr. David Seed

ENG 602: Dissertation

Summer 2007

Post-Cold War American Identities in Battlestar Galactica

The atomic bomb that leveled Hiroshima also blasted openings into a netherworld of consciousness where victory and defeat, enemy and self, threatened to merge.

Tom Engelhardt, The End of Victory Culture

The fission reactions of Fat Man and Little Boy over Hiroshima and Nagasaki were meant to be divisive reactions releasing energy from the breaking apart of atomic nuclei. However, those bombs began the first fission initiated cultural fusion reaction of merging “victory and defeat, [and] enemy and self” (Engelhardt 6).[i] This results in a crisis for the American consciousness, because, “with the end of the Cold War and the ‘loss of the enemy,’ American culture has entered a period of crisis that raises profound questions about national purpose and identity” (Engelhardt 10). He constructs his argument around examples including war narratives and popular culture including Science Fiction (SF). Engelhardt’s cycle of sneak attack, triumphalism, and identity crisis is repeating itself today. The 9/11 sneak attacks heralded the beginning of a new wave of fourth generation warfare brought to bear by Al-Qaeda on the secular Western democracies. The era of the Global War on Terrorism is even more problematic both ideologically and strategically than the Cold War, because of the following issues: Who is the enemy? Where is the enemy engaged? Is the enemy amongst us? How do we identify the enemy from ourselves? Metaphorical and explicit engagement of these issues is integral to the development of Post-Cold War SF including the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica.[ii]

Battlestar Galactica is uniquely situated to connect the Cold War and Post-Cold War eras. Also, its transformative engagement of identity and the enemy-other makes it well suited to exploring the shifts resulting from the crisis that Engelhardt describes. The original 1978 Battlestar Galactica and the 2003 re-imagined series are very different in scope, narrative, and confrontation with the paradigm crisis resulting from the shift from the Cold War to the Post-Cold War era.[iii] Their relationship provides points of reference embedded historically and culturally within these two eras. Additionally, Martin McGrath’s description of the original series is telling about its Cold War connections:

Comparisons between Glen A. Larson’s Battlestar Galactica from the 1970s and this modern incarnation are revealing. Larson, a conservative and Mormon, also filled the show with religious and political allegory, but it was one-dimensional. The original Battlestar Galactica transposed the writings of Mormon faith to a futuristic setting but the politics remained firmly rooted in the Cold War. His Cylons were militaristic “communists” in shiny armor and the battle was simply good versus evil. His human community was wholesome and, apart from a pantomime villain, united (McGrath 16).[iv]

It’s the “one-dimensionality,” or more accurately two-dimensionality, of the original series that labels it as a Cold War narrative based on conflicting political ideologies mapped over an “us versus them” narrative. Additionally, they were not actually called “militaristic communists,” but they behaved in Western perceived stereotypical ways, which include almighty top-down hierarchy, militaristic existence, expansionist tendencies, and lack free will. This kind of story is what Engelhardt calls “the American war story,” in which, “you had no choice. Either you pulled the trigger or you died, for war was invariably portrayed as a series of reactive incidents rather than organized and invasive campaigns” (Engelhardt 4-5). The original Battlestar Galactica series is by-and-large such an “American war story.” However, the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica goes beyond mere reflection and directly challenges Susan Sontag’s claim that, “there is absolutely no social criticism, of even the most implicit kind, in science fiction films” (Sontag 223).[v] Social commentary and confrontation of real world issues are built into the story rather than as mere metaphor or tangent.

I argue that there is a shift in SF to more directly engage contemporary issues, and I describe how the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica goes further than its 1978 source material in this regard. In this paper, I approach this shift from several different yet interrelated vectors including an analysis of the enemy-other Cylon threat and its destabilization of Western democratic identity, which reflects the reboot of Engelhardt’s cycle. I analyze the portrayal of human and alien/enemy-other identities in the two BSG series and the development of human and Cylon identities across time and the way in which they begin to blur and merge in the re-imagined series. This involves analyzing identities in each series separately and then exploring the way those identities are in dialog with the other series as well as culture at large. Then, I use those conclusions to answer if and to what extent there is an identity shift in SF from the Cold War to the Post-Cold War era and how that shift is connected to and represents cultural and historical developments.

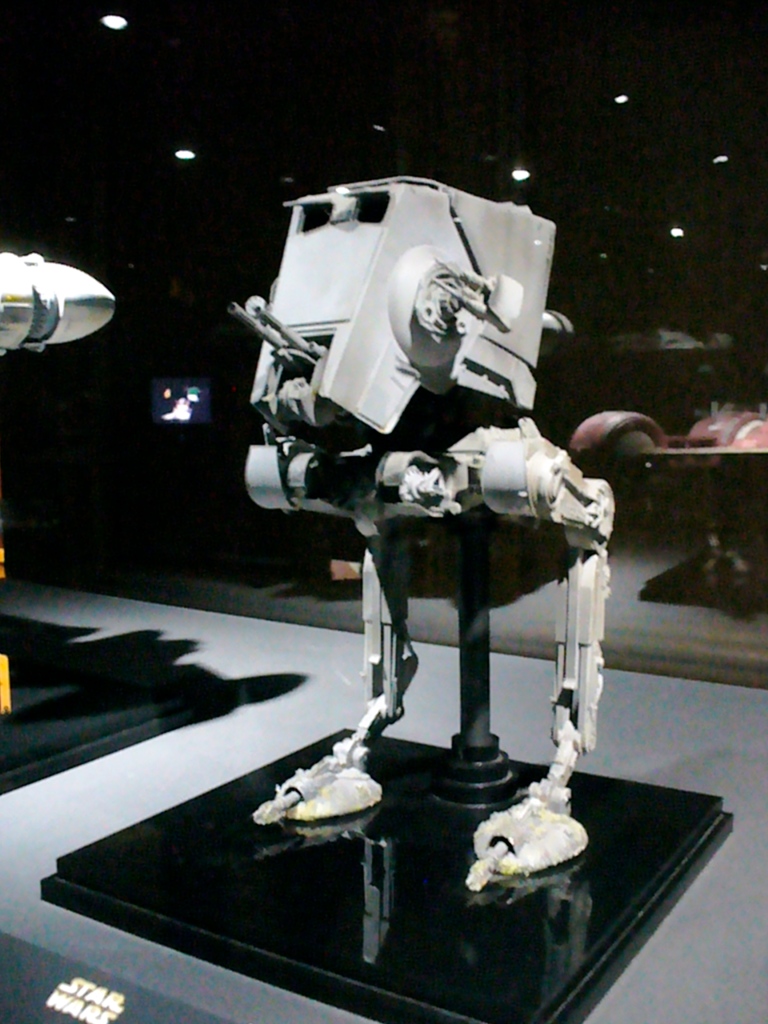

Glen A. Larson’s 1978 Battlestar Galactica is a two-dimensional version of Engelhardt’s cycle by incorporating mythology, technological renaissance, and Cold War ideology. It’s set in another part of the galaxy, possibly in another time, where humans are nearly eradicated by a powerful race of robots known as Cylons. The human survivors form a convoy of spaceships, protected by the battlestar Galactica, and set off in search of the mythical planet Earth. At its core, it’s a biblically inspired exodus story about fathers and sons, but the explicit visual threat arrives via the communistic Cylon robots.

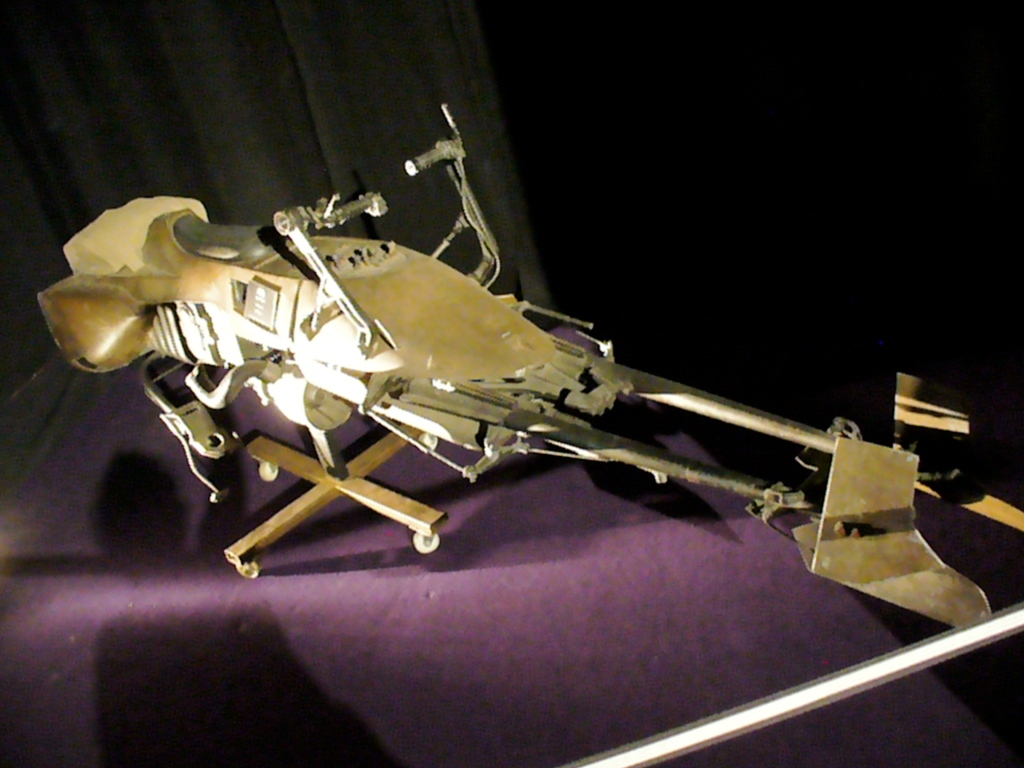

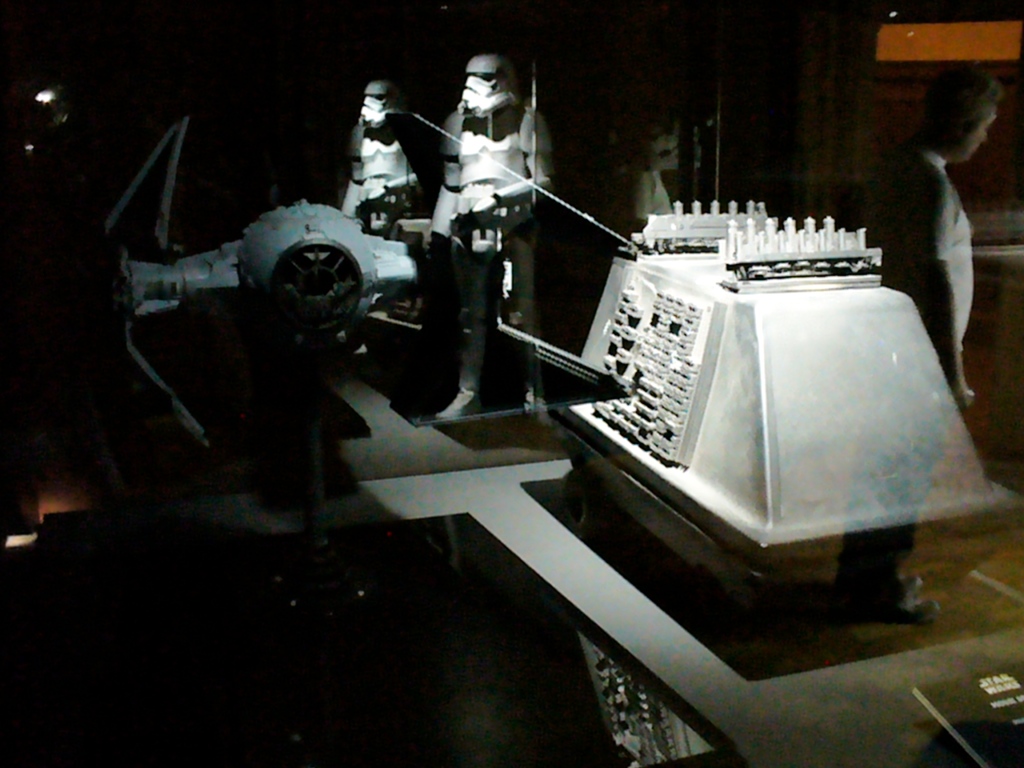

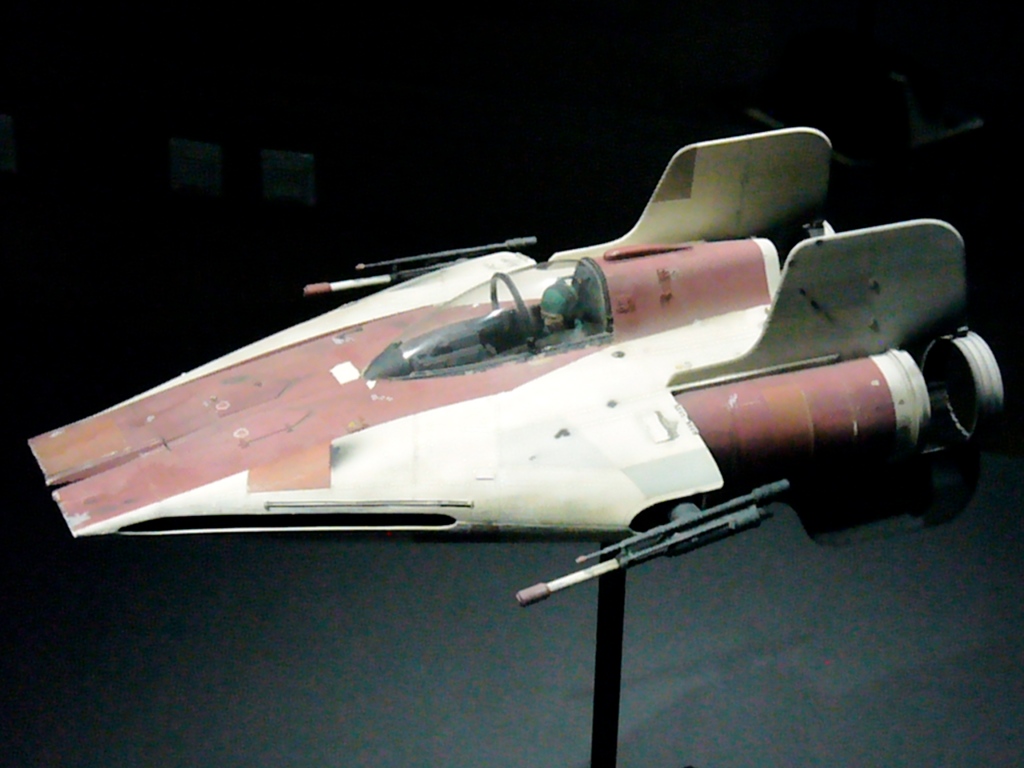

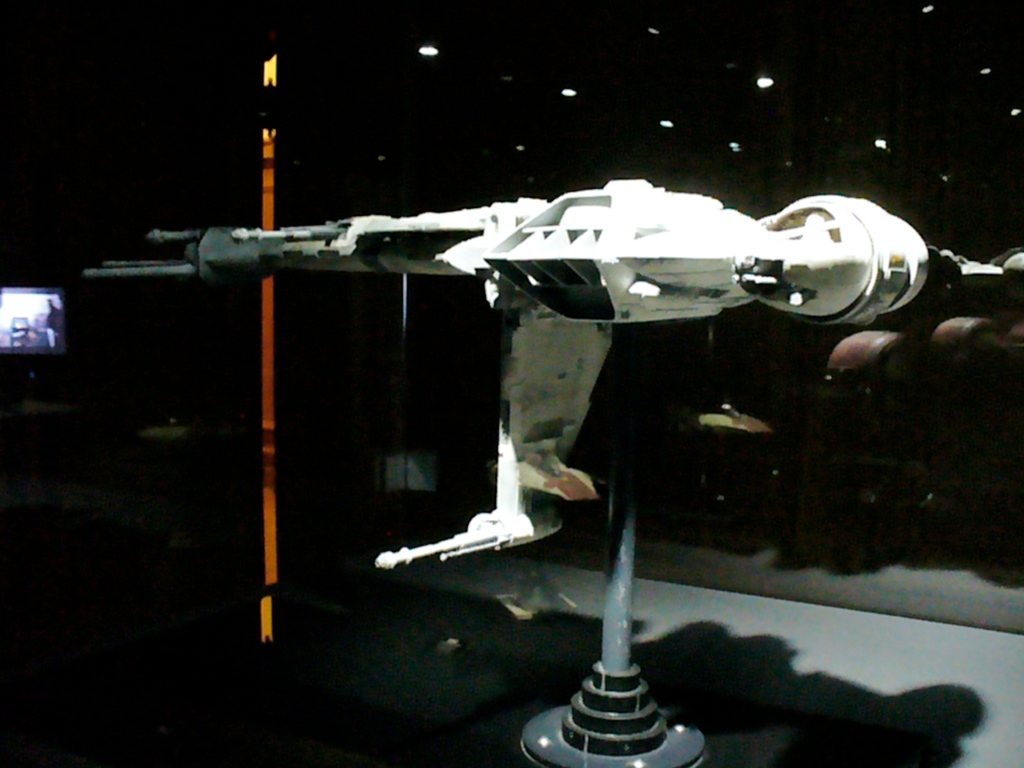

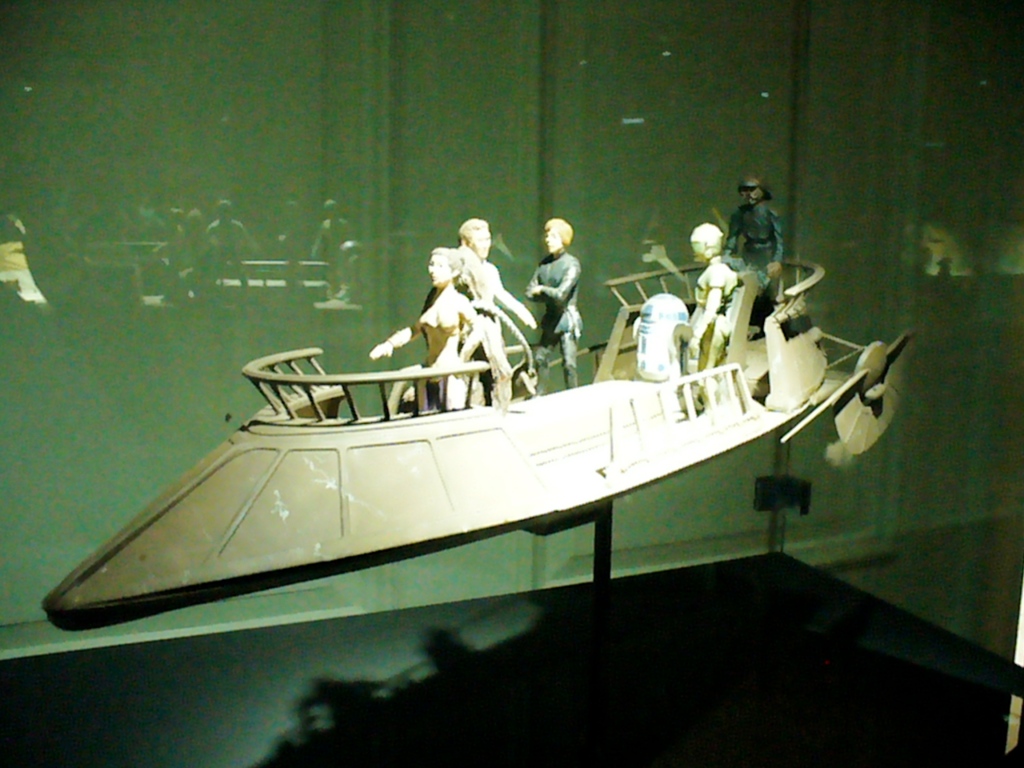

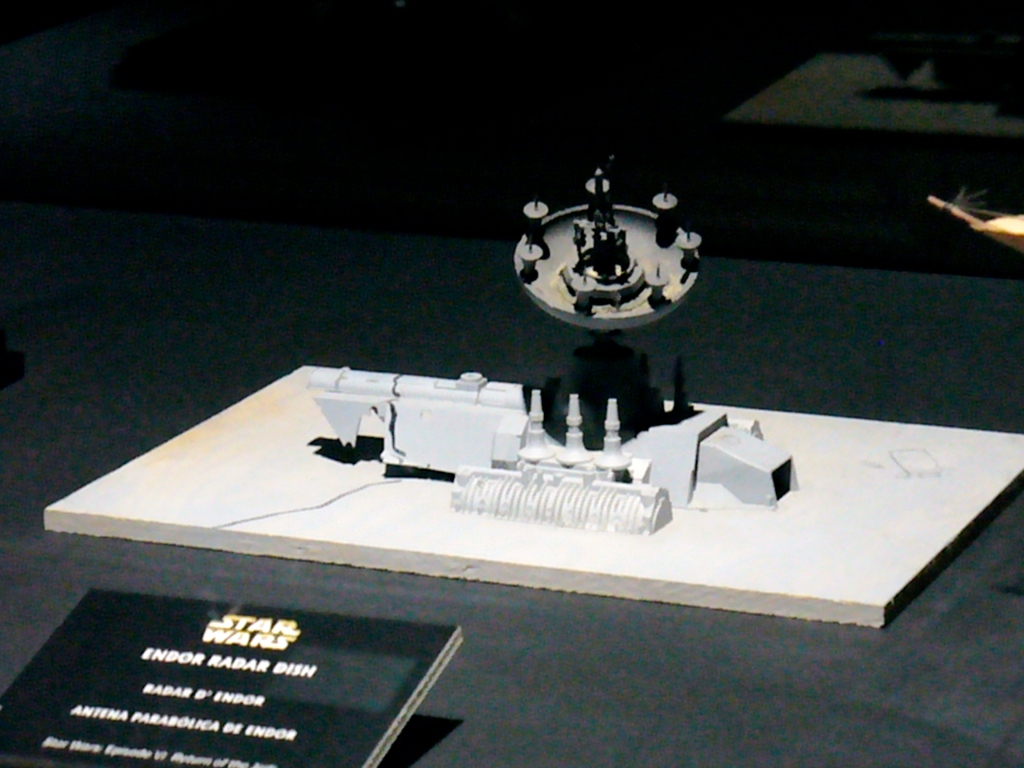

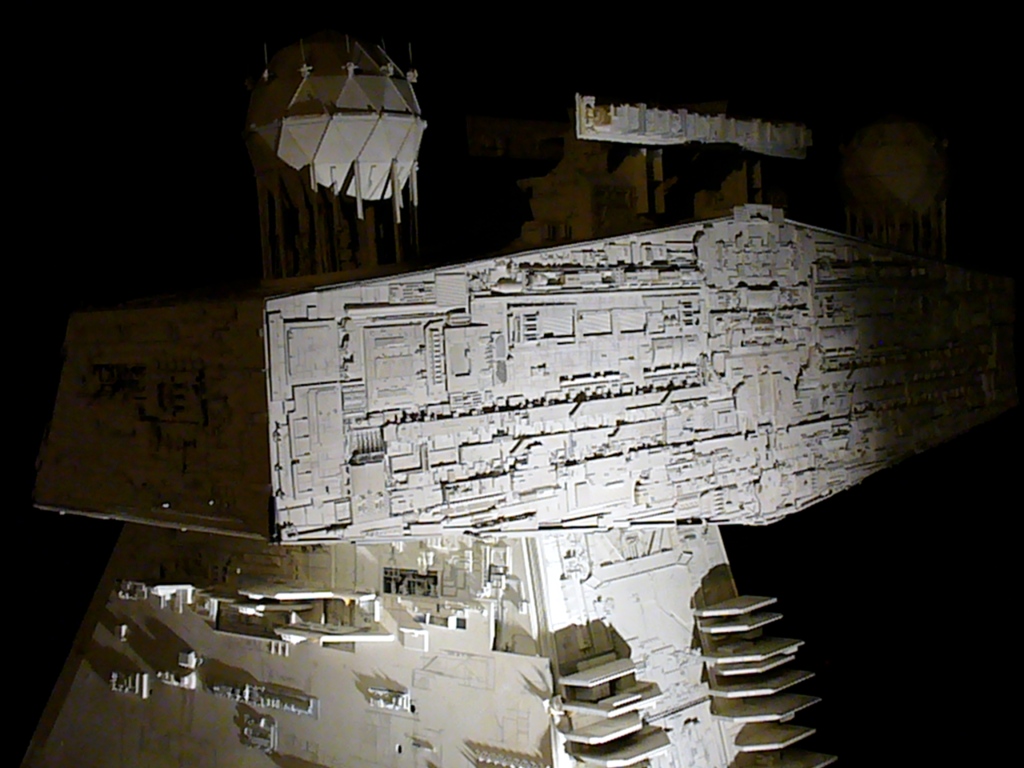

The first episode, “Saga of a Star World” was originally interrupted for the televised signing of the Camp David Peace Accords between Egypt and Israel on September 17, 1978, which was in the middle of the optimistic and arguably idealistic Carter presidency.[vi] Furthermore, Battlestar Galactica builds on space opera successes such as George Lucas’ 1977 film Star Wars[vii] and the even earlier “wagon train” to the stars television series, Gene Roddenberry’s 1966-1969 Star Trek.[viii] Its connection with Star Wars is further embedded in the Cold War power/political structure thanks to the media aping the phrase for Ronald Reagan’s proposed next generation military hardware and weaponry designed to lie in wait over the Earth in the vacuum of space. Reagan revealed the United States’ new plans in a March 23, 1983 speech that outlined the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)–what was often called “Star Wars” in the news. Reagan set out to use lasers and missiles to defend America from a preemptive attack by what he later termed the “Evil Empire.”

According to critics Michael Rogin and Frances Fitzgerald, Reagan’s SDI inspiration came from two likely sources: Murder in the Air (1940)[ix] and Torn Curtain (1966).[x] Rogin first points out that Reagan starred in Murder in the Air as the protector of a super weapon that brings down enemy aircraft with “electric currents.”[xi] Fitzgerald finds another filmic source for Reagan’s pet project in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, which is about a defensive anti-missile system. [xii] Fitzgerald, building on Rogin’s work, shows that Reagan used stories and lines from these and other films without attribution. His film background and integration of these lines encouraged Reagan to describe the world in a polarized way–the good American homeland versus the “Evil Empire” of the Soviet Union (Fitzgerald par. 13). Additionally, these films as well as Reagan’s own ideas about the dichotomy between what is simplistically delineated as the Western democracies and Eastern communist bloc is an oversimplification of a much more complex power and political matrix within which the United States and the USSR were situated.

The 1978 Battlestar Galactica, as a precursor to the Reagan administration and existing within the Cold War ideology reasserted by Reagan on his bully pulpit, is a reflection on culturally held beliefs in the United States at that time as well as an indicator of the shift from an idealistic Carter to the fear mongering Reagan.[xiii] SDI, like BSG, was a production revealing Reagan’s plan for the future of the Cold War through a protective shield. The shield itself could be thought of as a screen upon which the movie about this new technology is projected. Wills describes it best when he writes:

What is Star Wars but another, more complex projector meant to trace, in lasers and benign nuclear “searchlights,” the image of America itself across the widest screen of all? It is another premiere, a cosmic opening night (Reagan’s America 361).[xiv]

“The image of America itself” is also projected in SF works such as BSG. The original and re-imagined series reflect shifts in the way that image is projected as well as whether it should be accepted or reconsidered.

Despite the cultural web in which the 1978 BSG was created, Larson is very explicit about the things that he was thinking about in bringing the series to life. On the recent Battlestar Galactica: The Complete Epic Series DVD,[xv] he says in an interview:

I guess I was influenced by a number of things growing up, you know, I have Mormon origins, but [sic] always fascinated by the theories of things, for example, Greek mythology and the pyramids. I love von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? I got fascinated by all those themes and what emerged was Battlestar Galactica (“Creation”).

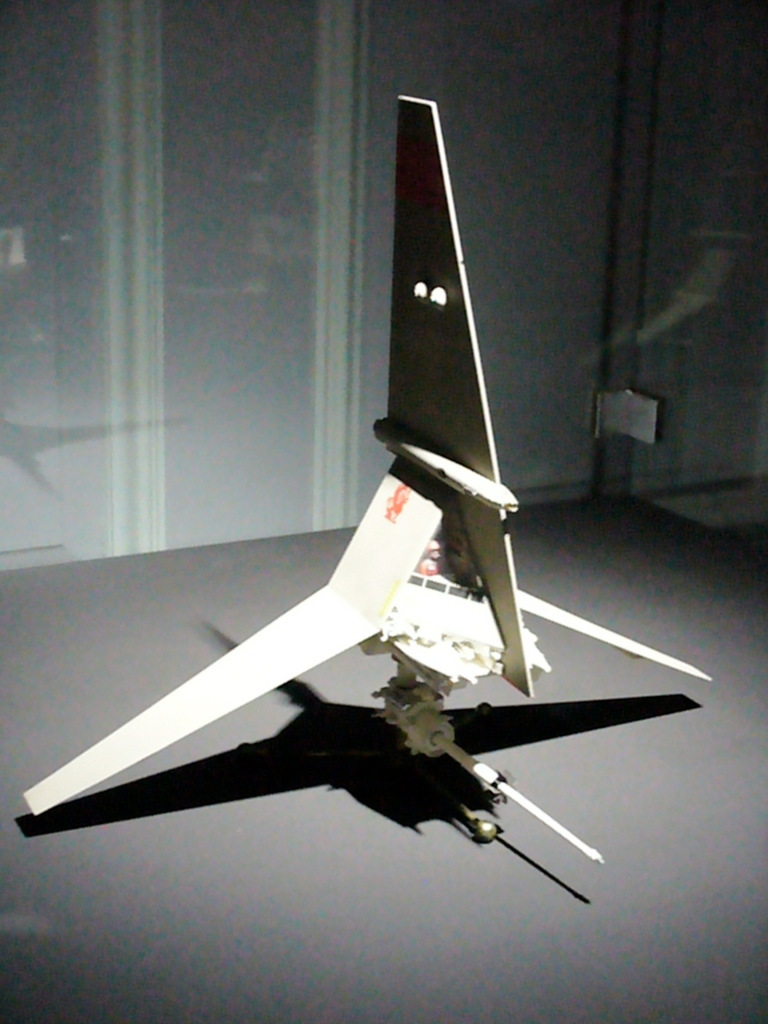

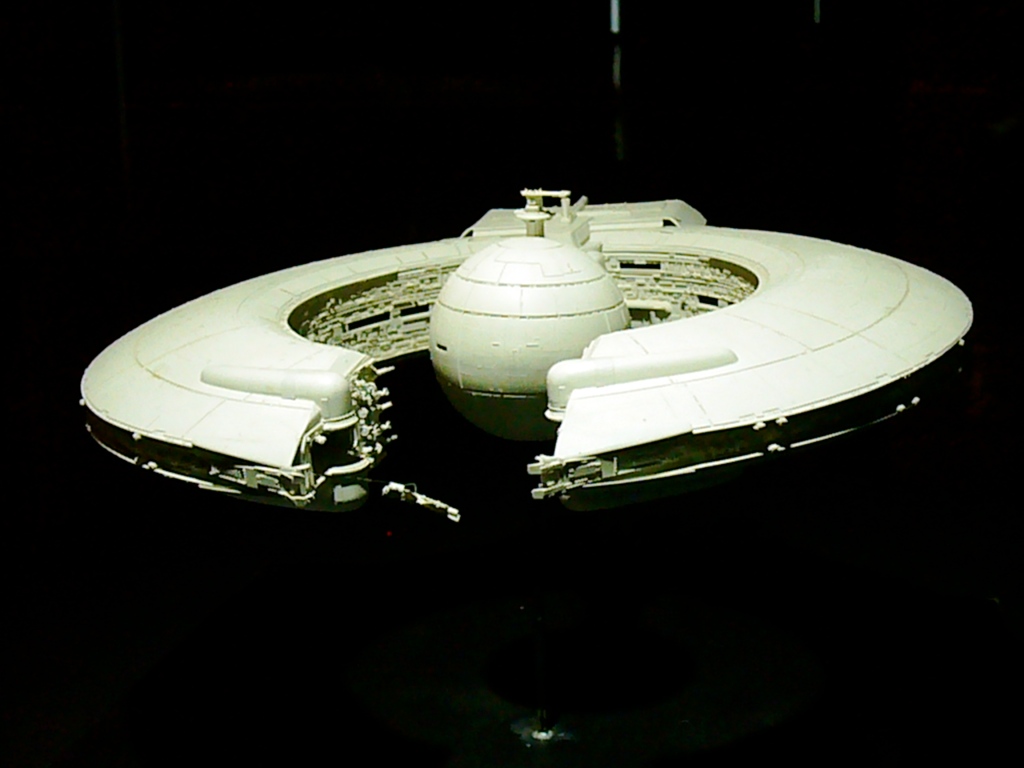

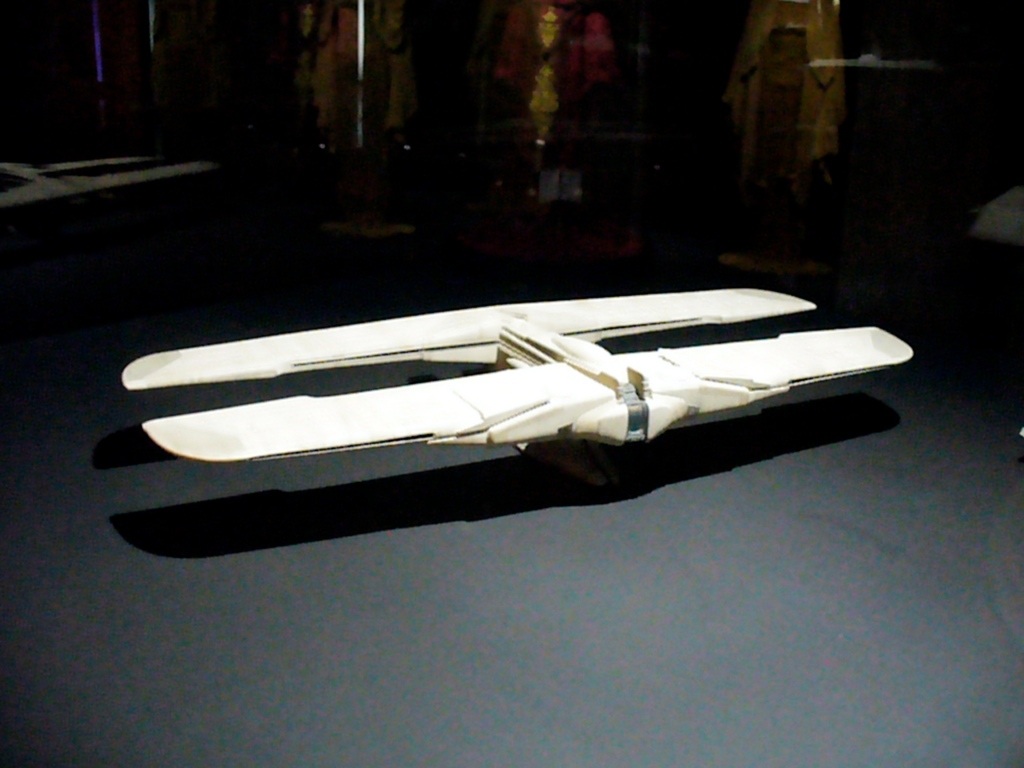

It’s clear in watching the original series that it owes much to mythology and religion. One key example is the democratic Quorum of Twelve, which consists of the leaders of the Twelve Colonies of Man. This is borrowed from Judeo-Christian belief and carried down through Mormonism based on the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Additionally, Earth represents a thirteen, lost tribe, and could be said to correspond to the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Another obvious connection is the insistent naming characters with the names of Greek and Roman gods and goddesses such as Apollo and Athena. Larson’s choice to mention Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? (1968)[xvi] is both fantastic and interesting. Von Däniken’s claims that many of the triumphs of the past seem improbable without the intervention of aliens or superior technology from a lost (tribe) civilization. Larson incorporates this in BSG by displacing time and space from our contemporary Earth to a far past or far future with the surviving humans of Galatica’s fleet existing in their own here-and-now. However, BSG’s look and feel, reconnecting to where this discussion began, is related to that of Star Wars. Larson brought on John Dykstra, the lead of George Lucas’ Special Visual Effects department for Star Wars to create the special effects for BSG, but to much less visual impact. Larson himself probably won’t admit to any connection to Star Wars, because of the dismissed litigation initiated by 20th Century Fox against Universal Studios following the original release of BSG.

BSG was on the air for one season, before it was canceled by ABC. There are a variety of reasons for BSG’s cancellation including a ratings decline following the pilot and the staggering cost of each episode despite recycling special effects footage. Some sources point to ABC misinterpreting BSG’s ratings in the Sunday time slot in order to cancel the show rather than give the true reason, which was to drop such a costly show (Larocque G7).[xvii] Whatever the reason, there was a follow-up movie based on re-edited material from the television series, and a half-season run of a continuation of BSG called Galactica 1980, which is about the fleet protecting a contemporary Earth from Cylons. This second failed attempt at BSG on television illustrated the producers and writer’s misconception that historicity and power/political matrices are transposable and easily remapped to other settings in time-and-space merely by a change of costume.

The Battlestar Galactica – Character, Technology Mediation, or Both?

You’ll see things here that look odd, even antiquated to modern eyes. Phones with cords. Awkward manual valves. Computers that unfairly deserve the name. It was all designed to operate against an enemy who could infiltrate, even disrupt, the most basic computer systems. Galactica is a reminder of a time when we were so frightened by our enemies that we literally looked backward for protection.

Aaron Doral/Cylon Number Five (Matthew Bennett) in the 2003 BSG Mini-Series

In the original and re-imagined BSG series, the Cylons are humanity’s enemy-other. The original Cylons are armor clad robots, and the re-imagined Cylons include suped-up versions of their original warriors as well as humanity’s doppelganger embodied in infiltrating cyborgs that are nearly indistinguishable from humanity. One such human-like Cylon is Aaron Doral, an undercover Cylon operative who performs himself as a public relations specialist. He’s attached to the decommissioning ceremony of the battlestar Galactica, and he gives the above description of the Galactica to a troop of press reporters. This early scene from the Mini-Series is terribly ironic that the hiding-in-plain-sight Cylon operative, Doral, is relating the history of this throwback from the Cylon Wars. Additionally, he is the pinnacle of computer development as a living, thinking machine, and he tells the reporters that Galactica’s “computers…unfairly deserve the name.” He is also quite aware how effective the Cylon enemy is at infiltration and disruption. Most importantly, he makes the point that “we,” meaning humanity, “looked backward for protection,” which has the double meaning of looking back twenty-five years from the re-imagined series to the original BSG and relying on older and paradoxically less vulnerable technology. However, there is a third meaning, which is that Doral, as a Cylon, could implicitly mean that the machine Cylon race looks backward to its parents, humanity, and the human body as a means for infiltration and disruption thereby effecting protection from humanity by undermining it through doppelganger mirroring of it.

The Galactica and humanity’s quest for Earth in both BSG series is a retelling of the return to the Earthly Garden and a pastoral existence as argued by Leo Marx and later, Sharona Ben-Tov. Marx writes about the tension between technology and the pastoral in his 1964 work, The Machine in the Garden. [xviii] He discusses the contradictory conclusion in Industrial Era American literature that the non-technological pastoral garden may be recreated through the use and embrace of technology. BSG is a high tech narrative that is explicitly about humanity’s return to the mythical good place–Earth. Ben-Tov extends Marx’s critique to SF and the Earthly Garden myth when she writes:

Unlike the texts that Marx surveys, however, science fiction does not try to temper hopefulness with history. Instead, it tries to create immunity from history. It reveals a curious dynamic: the greater our yearning for a return to the garden, the more we invest in technology as the purveyor of the unconstrained existence that we associate with the garden. Science fiction’s national mode of thinking boils down to a paradox: the American imagination seeks to replace nature with a technological, made-made world in order to return to the garden of American nature” (Ben-Tov 9) .[xix]

Both of Ben-Tov’s points are mediated by the Galactica in the re-imagined series. It serves as the stage and backdrop against which “contemporary themes” play out amongst the characters on both sides of the human-Cylon divide. Furthermore, the Earthly Paradise is the mythical planet known to the BSG characters as Earth. It is both a real and an imaginary place, but for them, it’s only achievable through the technology of spaceflight. Therefore, Galactica is the technology and science fiction that “reinforces American ideologies,” and it’s the technological means to arrive at the Earthly Paradise or as Leo Marx called it, the pastoral existence.

Science fiction, including BSG, “continually adapts contemporary themes…to an older, invariant ideological structure, in which nature’s “death” and the Cartensian re-definition of self are the central drama” (Ben-Tov 8). The “re-definition of self” is integral to the overall plot of the re-imagined BSG where personal anxieties about the self and true identity are continually bantered about. SF and BSG also, “actively reinforces American ideologies,” which are reinforced on-board the Galactica through military power and command structures, efficiency, democracy, and individuality epitomized by the stereotypical Navy/Air Force “Top Gun,” who is both anti-command and the best pilot. These ideals further integrate into the mode of production and the fulfillment of the needs of the fleet with consumables such as water, food, and Tylium “rocket fuel.” These are exacerbated by the collective needs of the fleet inhabitants and the labor making those things possible, which includes prisoner workers in “Bastille Day” (21 January 2005), and union organization in “Dirty Hands” (25 February 2007). Through all this, the Galactica holds true maintaining its course towards Earth and the Eastern seaboard of North America as shown at the end of “Crossroads, Part II” (25 March 2007).

The re-imagined BSG recycles American tropes as its “national mode of thinking.” The ultimate goal of humanity may be Earth, but implicitly it’s the North American frontier via their technological “wagon train.” Ben-Tov connects this to the pastoral garden by saying, “Science fiction’s national mode of thinking boils down to a paradox: the American imagination seeks to replace nature with a technological, man-made world in order to return to the garden of American nature” [author’s emphasis] (Ben-Tov 9). The re-imagined Galactica, relying on antiquated technology, is the means to return to “the garden of American nature.” As implied by the title of the season three episode, finding Earth and evading the advanced technological threat embodied in the Cylons, will allow humanity to “[Take] a Break From All [Their] Worries.”[xx]

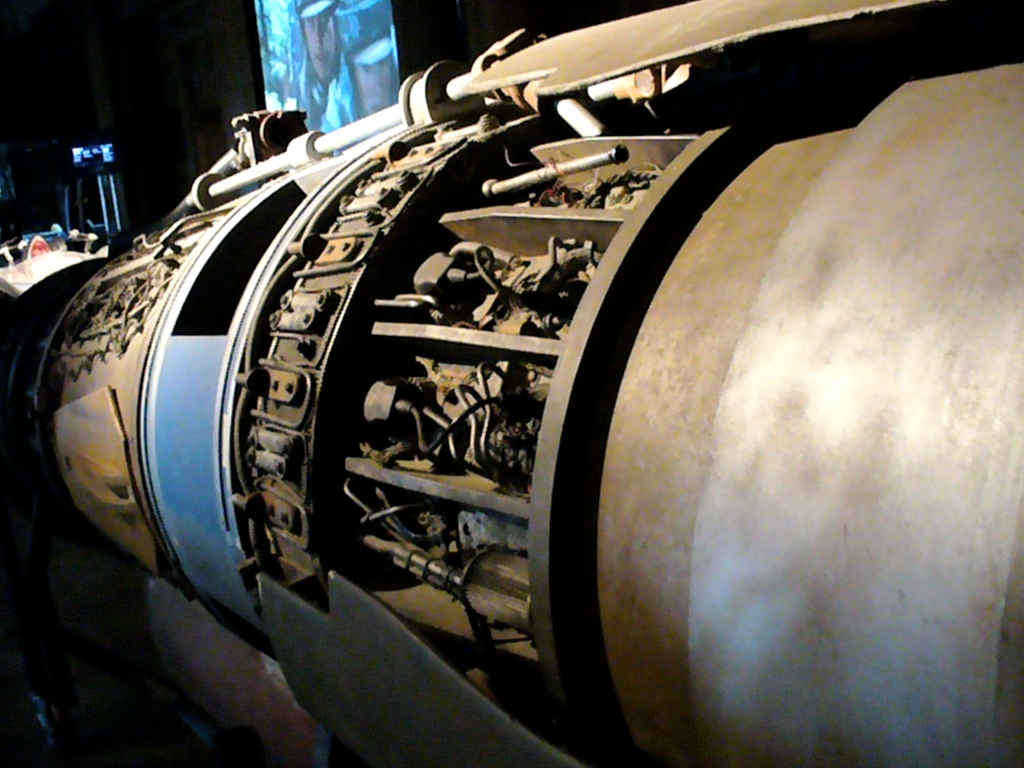

The new Galactica is more Nostromo from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979)[xxi] than the original’s immaculate Starship Enterprise-like spit and polish of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966-1969). As the re-imagined series progresses, the Galactica reflects a history embedded in grime, scarring, and damage. It’s appearance is a sort of memory and record of humanity’s exodus in search of Earth. This physical recording and recall of events are also reflected in other SF space vehicles such as the Millennium Falcon from the original Star Wars trilogy and Serenity from Firefly.[xxii] Antithetical examples include the anonymous Star Destroyers from George Lucas’ universe and Discovery One from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.[xxiii] The original battlestar Galactica reflects these latter examples. In many regards, Larson’s Galactica resembles a safe environment on a sound stage. It’s not fully integrated and whole. It’s built up from a floor in the way one would frame a house (albeit a far future one). One can imagine high-tech drywallers at work in the 1978 Galactica as envisioned by Dante and Randal in the movie Clerks.[xxiv] This more basic, yet advanced spaceship, reflects humanity’s embracing technology following the Caprician renaissance. A great deal of money was spent on the state of the art special effects and Core Command, Galactica’s bridge, features half-a-million dollars worth of Tektronics computer hardware to simulate a real starship bridge. This Cold War investment and reliance on technology is emblematized by Reagan’s SDI/Star Wars missile defense system. Technology is the way to creating a safe and pastoral existence in the future. The re-imagined Galactica relies on the contemporary language of computer networks, viruses, and programming backdoors to challenge the perception that newer technology is inherently better, safer, and more secure. Viewers identify with this verbiage in the wake of computer worms crippling ATM networks and increasing reportage of cyberwarfare in the Post-Cold War era. Therefore, the re-imagined BSG questions the Cold War belief and wholesale investment in new technology to return humanity to the Earthly Garden, whereas the original Galactica epitomized the state-of-the-art and its ability to take humanity safely to the promised paradise.

The Cylon Sneak Attack and American Triumphalism

Both versions or visions of Battlestar Galactica begin with what Larson calls, “That big sneak attack,” which he describes as a “sort of Pearl Harbor in space,” and those persons who survive, “figured they had to get away and fight another day” (“Created”). What Engelhardt says about films following the Pearl Harbor attack, “defeat was only a spring board for victory,” may also be applied to the two Battlestar Galactica series ( Engelhardt 3). The Cylon sneak attack in both series establishes their identity as the enemy-other along with aligning them with treachery and deception. Additionally, the new Cylon threat is significantly different than the one in which humanity fought forty years prior to the events taking place in the 2003 series. The past involved strategic military engagements between Cylon warriors and the human military. Cylon war making changes in both series–a Japanese-inspired sneak attack in the original series and an infiltrative disabling of humanity’s defenses prior to an armistice ending near-annihilation. This mirrors the objectification and “othering” of the Japanese during World War II. Furthermore, Engelhardt describes the rise of triumphalism and the call for absolute victory following the beginning of World War II. However, the American triumphal identity falters in the Cold War due to stalemates and losses in Korea and Vietnam. This is reflected in both series when they cut and run in the original, and President Roslin convincing Commander Adama the war was over from the beginning in the latter. However, identity crisis isn’t explored among the “wholesome” community of humans in the 1978 series, but it is a very important and dramatic issue in the 2003 series. Underlying the threat to humanity in both series are the Cylon invaders. In both cases, Cylons provide an enemy-other from which humanity defines itself, but its in the 2003 series that human identity is challenged and destabilized by a new and unexpected Cylon threat.

In the original Battlestar Galactica, Cylons were created by a then extinct reptilian race for labor. The other Cylons were created by the other reptilians. On the one hand this makes the Cylons doubly other, because they were created by bug eyed monsters that the audience never sees, but is decidedly different than humanity. Another way of looking at this is the oddity that Cylons resemble humans in many respects. They literally appear to be men walking around in shining armor. To what extent do humans resemble the Cylon’s reptilian creators or vice versa? Are we meant to identify with these original Cylons in some way, because they fit into our own historical and mythic story past about knights in armor? These questions are not directly engaged in the original BSG series. Another reading of the Cylons’ creators is the association of the reptilian race and the devil as he appears in the Eden Garden as a snake tempting Eve with the fruit of knowledge. This directly challenges the American impulse to use technology to return to Paradise, because the Cylons are the ultimate technology and that technology is an explicit threat to humanity. On the other hand, that’s assuming an anti-evolutionary stance in that the Cylon-human conflict is the inevitable showdown between evolutionary competitors. In this light, the original Cylon-human conflict is less Oedipal than the re-imagined Cylon-human conflict in that it’s humanity’s children, the Cylons, returning to kill their parents (i.e., all humanity, but specifically the male scientist).

Humans and Cylons are at odds with one another after humanity fights alongside another galactic race threatened by the marauding Cylons. Viewing humanity as a threat to their galactic expansion, the Cylons decide to obliterate the biologically weak humans with their superior machine strength and efficiency. The otherness of the machine Cylons is utilized in order to create a two-dimensional conflict between them and humanity. Thus, the conflict is delineated between the apparent, but later problematized, opposites of machines and flesh.

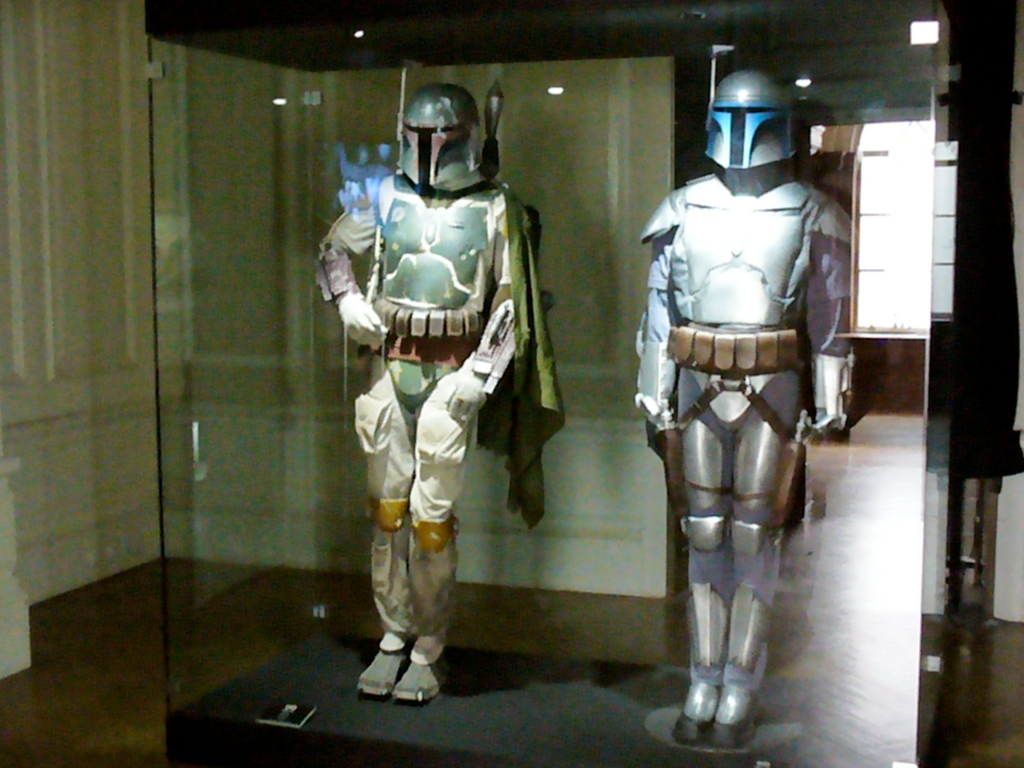

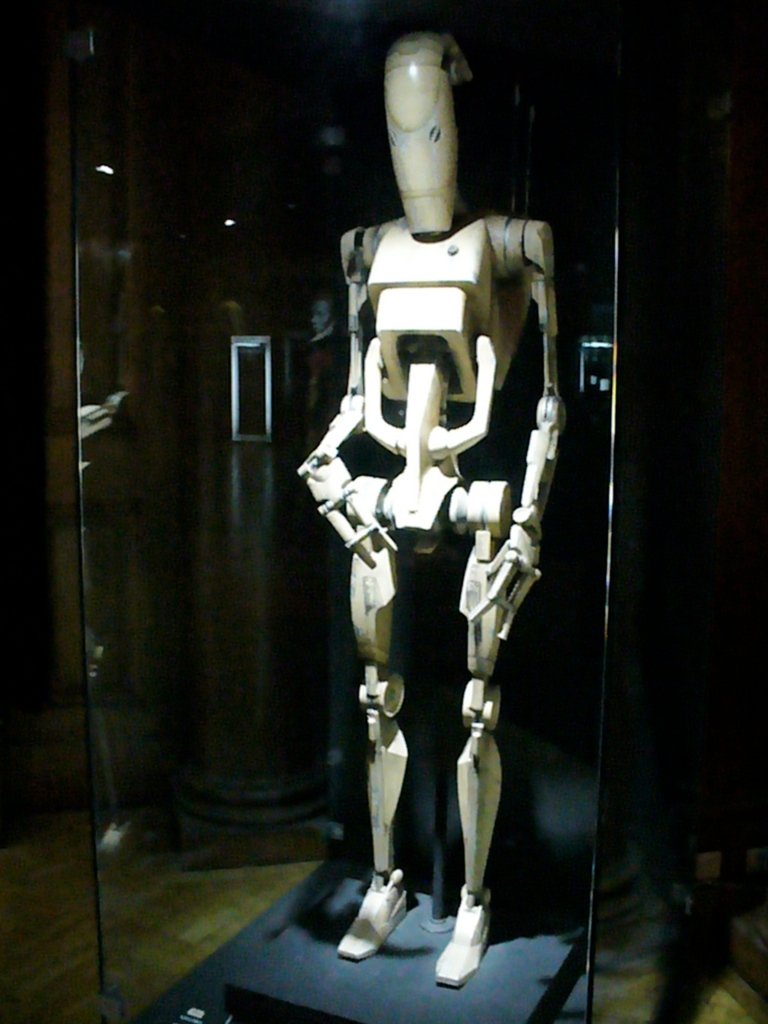

The Cylon Centurion or warrior is the most often seen Cylon in the original series. The sameness of the Centurions defines them as a single role. They look like a person wearing a suit of armor, and they serve as good targets for the Galactica crew. Along with their armor, they don a laser blaster as well as a sword. Their armor features an immaculate shine like polished chrome and their helmets are reminiscent of Darth Vader’s mask–wide trapezoidal shape covering the nose and mouth areas and their “eye” is a wide bar extending from one side of the face to the other with a red pulse intently and steadily gliding from one side to the other. The red eye, being the window to the soul, could imply a communist threat. Other implications of the glowing red “eye” include warning, danger, and even blood. Alternatively, the sliding red light acts as a mask to hide their eyes, which has its own sinister connotations. Red is a popular color in films of the Cold War era and one eminently well-known example is the 1953 George Pal production of The War of the Worlds.[xxv] The film and its original movie poster both literally bleed red. Red film references include the Martian heat-ray, the color of the Martians’ skin, and even the red planet, Mars. Red serves as a warning to the viewer, and it serves a double meaning as a reflection of the Cold War threat and enemy to democracy–communism.

Another connection between the 1978 Cylons and communism has to do with their command structure and social organization. They blindly follow top-down orders from their supreme ruler with the acknowledgement, “By your command.” Orders are handed down by special IL, or Imperious Leader, models. One such IL model is called Lucifer, and its assigned to observe and work with the villainous human, Lord Baltar, whose name is tellingly an anagram for “lab rat.” Lucifer’s head has a generally human shape, and a basaltic-blue color with two red eye slits. Its robotic body is covered by a long red robe, and the character was voiced by Jonathan Harris who is most recognized as the cowardly bad guy from Lost in Space.[xxvi] Additionally, there are similarities between Wellsian ideas about the evolution of humanity such that the brain grows to occult the body. One example of this is the Morlocks in The Time Machine.[xxvii] This is illustrated in the original BSG through the creative use of camera angle and framing to enlarge the Imperious Leader on a tall dais waiting to dispense orders to the drone/worker/warrior Cylon Centurions.

Consider the etymological significance to the name, Cylon. Larson more than likely appropriated the name from Cylon (or Kylon) of Athens. Cylon of Athens was an Olympic games winner, who attempted to take control of the city of Athens and establish a tyranny in 632 BC. He and his followers failed, but his attempt revealed that those persons who had recently acquired wealth wanted greater political recognition and power. This in itself is interesting considering that the Cylons of Battlestar Galactica are essentially a working class that gained (political) consciousness following the extinction of their reptilian overlords and creators. Unfettered by their former masters, the Cylons acquired new resources by force. Additionally, their expansionist nature belies their voracious capacity and need for resources to continue their existence as well as empire. Another obvious connection with the name is cyborg and cybernetics. The original Cylons are machine, but have an anthropomorphized appearance, but the new Cylons are flesh and machine are more deserving earn the distinction of being cyborgs.

Fast-forward twenty-five years to Ronald D. Moore’s re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, which was introduced in 2003. Unlike Larson prior to the original series, Moore has an established record in SF through his prior screenwriting and producing credits on several Star Trek series. On the re-imagined series Larson is credited as a “creative consultant,” but Gary Westfahl writes that, “although new producer Ronald D. Moore, who demonstrated his skills in science fiction with work for the Star Trek franchise, has thankfully displayed no inclination to consult with Larson about anything” (Westfahl par. 7).[xxviii]

The re-imagined Battlestar Galactica first aired on December 8, 2003 two years in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in the United States and subsequent war with Afghanistan, and nine months after the United States’ invasion of Iraq. The US occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq as well as the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp of “enemy combatants” in the Global War on Terrorism feature into the new series, particularly the second and third seasons. The earlier first and second seasons follow Cold War lines of political friction between the Executive Branch of the US government and the military as laid out by President Dwight Eisenhower’s farewell speech to the nation[xxix] that warned the American public of the “military-industrial complex” (17 January 1961) and Bailey and Knebel’s Cold War political thriller from 1962, Seven Days in May, which describes an attempted coup.[xxx]

Interestingly (and coincidentally) for the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, there were several key events that took place in 1978, the same year that the original Battlestar Galactica series was released, that were prescient for the new series. The year BSG was first released was also the year that David Rorvik published his fraudulent, but poignant book about human cloning, In His Image: The Cloning of a Man.[xxxi] The controversy surrounding this book reflects the anxiety American’s feel about the technological appropriation of reproduction and the artificial construction of humanity’s doppelganger via that technology.[xxxii] Cloning and copying of human-like individuals is a powerful and integral part of the re-imagined BSG, particularly involving the identity of the enemy-other. On July 25, Louise Brown is born–the first in vitro fertilization birth, which is connected to the growing artificiality of reproduction. Also, President Jimmy Carter decided on April 7, 1978 to end development on the neutron bomb, which was intended to kill people with radiation but leave structures in tact. This kind of weapon was arguably used by the Cylons in addition to traditional thermonuclear weapons to kill the human inhabitants of the Twelve Colonies due to the visual evidence that many buildings, unlike the inhabitants, survive the attack.

Moore incorporated Larson’s idea of a Cylon sneak attack and the resulting human exodus, which initially galvanized humanity as virtuous and the Cylon threat as insidious. However, he changed the story in several significant ways. These include the important change that the Cylons were created by man as slave labor, they rebel, and fight a protracted war that ends in an armistice forty years prior to the series’ beginning. Most importantly, there is a group of twelve Cylon models that appear and act human for all practical intents and purposes, but were unknown to humanity until after the opening sneak attack. These human-like Cylons serve as the face and voice for the Cylons instead of the chrome robot killing machines of the earlier series. These twelve human-like Cylon models are the basis for many copies, and each copy has its own experiences and identity that is shared with all of the other Cylons. Initially, it’s revealed that there are seven known human-like Cylons as well as the unknown “Final Five.” The Cylon network on-board their large basestar ships is represented by falling red-colored glyphs in streams of water and biological goo in which Cylons immerse their hands to interface the network. At this interstice, a Cylon communes with what could be considered a hive mind, but a more accurate analogy might be a market of many voices that often shout everything, but may also chose to keep some things to themselves. It’s this act, which serves as one aspect of their individuality. The hive mind requires total openness and an unrestricted sharing–a communism of the soul. The new Cylon models are hybrid creatures masquerading as human and exist in an anarchistic collective. This affords these new Cylons a certain autonomy and individuality within certain bounds that can be crossed as in the case of the Number Three/D’Anna model’s deactivation or “boxing.” This may sound mutually exclusive, but their existence as hybrid creatures (i.e., cyborgs), visually as well as virtually in thought and mind, is the bringing together of two different things–humanity and machine. These advanced human-like Cylons withhold some aspects of their life and make choices that may be diametrically opposed to the will of the collective in order to evince change. A final noteworthy difference between the two series is that the Cylons in the original Battlestar Galactica operated within a communistic top-down hierarchy, whereas the re-imagined Cylons administer collectively by consensus following an anarchistic model.[xxxiii]

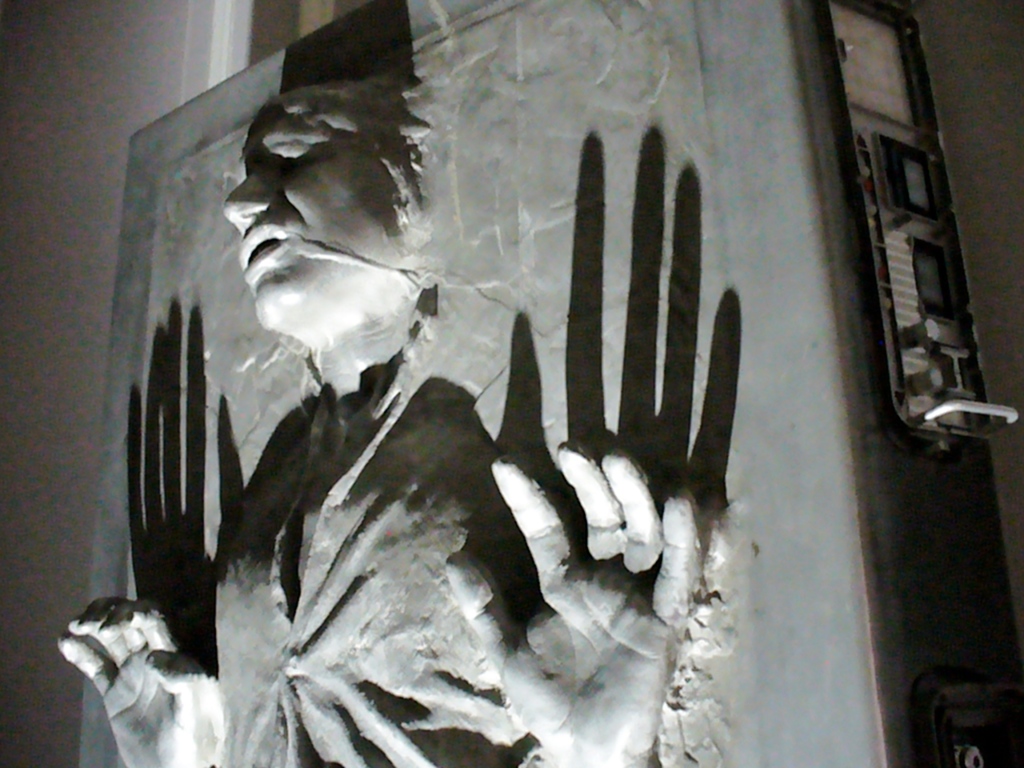

One troubling aspect of these new Cylons is that there are sleeper Cylons, which live amongst humanity not knowing their true identity until the receipt of a special signal or a timer goes off. This troubling development is reminiscent of replicants’ implanted memories in Blade Runner[xxxiv] and the secret Communist programming of individuals in The Manchurian Candidate.[xxxv] This culminates in the season one finale when the number eight Cylon sleeper agent known as Sharon “Boomer” Valerii attempts to assassinate Commander Adama.

Even more disturbing are the Final Five Cylons, because their identity is unknown to both humanity and the Cylons. The Final Five raise important questions such as: Whose side are they on? When revealed, how will this revelation affect their accepted identity? The Final Five destabilize human as well as Cylon identities. In the season three finale, “Crossroads, Part II” (25 March 2007), four of the final five Cylons are revealed as integral characters to the Galactica. As the klaxons blast out warning of an imminent Cylon ambush (which is another connection with Engelhardt), one of the four final five takes a personal stand regarding what this revelation means. Colonel Tigh tells the other three newly revealed Cylons, “The ship is under attack. We do our jobs. Report to your stations.” When Tyrol questions the order, Tigh goes on to say, “My name is Saul Tigh. I’m an officer in the Colonial Fleet. Whatever else I am, whatever else that means, that’s the man I want to be. And if I die today, that’s the man I’ll be.” Tigh chooses to perform the identity he believes himself to be. What else does it mean to be someone or something different than what you believe yourself to be? This is the central problem of identity. Labels and identities are meted out by others as well as by ourselves. Threats to one’s identity come from within and without, and this is ever more present in the amorphousness in today’s world of ideological battlefields spanning continents and individuals everywhere.

The Cylon enemy-other identity is established at the beginning of the 2003 series. However, humanity’s actions prior to the war and after the sneak attack destabilize the understood “right” and “good” of humanity. These identity issues connect to the here-and-now in that the Cylons become us, and we, them. Moore and his writers have been cognizant to muddy the waters on both sides of the human-Cylon conflict in order to further break down the barriers of our accepted beliefs about who is really good or evil. Furthermore, the lines between us in the Western democracies blur with those persons challenging us with fourth generational warfare. To better understand our conception of the enemy-other and the connection between Cylons and our here-and-now it’s important to reflect on the words of Philip K. Dick from his 1973 “The Android and the Human.”. He said, “rather than learning about ourselves by studying our constructs, perhaps we should make the attempt to comprehend what our constructs are up to by looking into what we ourselves are up to” (Dick 5).[xxxvi]

Commander Adama – Wholesome to Ethical Pragmatist

Humanity is the target of the Cylons in both Larson’s BSG and Moore’s re-imagined BSG. In Larson’s original BSG, McGrath points out, they are “wholesome” and “united” (16). Humanity’s leader is Commander Adama (Lorne Greene). Before the Cylon sneak attack, he was as much a political leader as a military leader. He served on the Council of the Twelve, which governs the Twelve Colonies, and he commands the military space faring battleship Galactica. Adama’s name obviously has connections with Adam, or one could go so far as to say it’s an anagram of “a(n) Adam” or a new beginning or founder of the future for humanity. However, Adama’s role is more like Moses leading his people to the promised land away from a powerful and persecuting kingdom. Much like the Israelites, these distant Twelve Colonies of Man mirror the Twelve Tribes of Israel, and as such, Adama unites the people with himself serving as their political, military, and spiritual leader. Like the Israelites, humanity in BSG are always traveling in order to avoid persecution by the Cylons and seek refuge in the “promised land” of Earth. Adama relies on religious scriptures that also serve as a roadmap to the fabled planet Earth. The religious texts serve as both a personal guide for spiritual fulfillment as well a literal map leading the way through the stars to the forgotten planet Earth. Adama assumes his position as gifted leader in much the same way as he was the de facto authority figure in Bonanza as Ben Cartwright.[xxxvii] BSG is very much a show about fathers and sons as was Bonanza. Adama/Ben Cartwright is the patriarchal father figure for his own children as well as the people/children of the fleet. Also, consider the name, Ben, which is short for Benjamin and one of the tribes of Israel. He takes it upon himself to be their guide through life (what is commonly referred to as the “episode of the week”) as well as on their journey to a refuge prophesied in their ancient religious texts. Adama also appears to be a feminized version of Adam, which suggests another kind of origin story–i.e., the origin of humanity in Judeo-Christian belief.

The 2003 BSG maintains a modicum of wholesomeness while injecting a shot of nitrous oxide infused reality that colors humanity’s survivors less than innocent yet more believable as archetype breaking fully integrated individuals. Roles are reversed, some characters added, and gender reassigned. These shifts are direct evidence that the re-imagined BSG producers and writers are willing to go beyond the original source material to completely engage the cultural changes and historical developments following the end of the Cold War.

The producers’ choice to have Edward James Olmos take the role of Commander William “Husher” Adama in the re-imagined BSG is very telling about the cultural changes since the original series. Olmos is an American actor of Mexican descent and he’s also one-quarter Hungarian Jewish (Olmos was originally spelt Olmosh).[xxxviii] Like the characters played by Lorne Greene, Olmos has portrayed several fatherly figures in his other productions. He played Jamie Escalante in Stand and Deliver (1988).[xxxix] In that role, based on the real-life math teacher by the same name, he became a mentor to a class of impoverished youth in Los Angeles. In 1995, he assumed the role of Paco in the film My Family, which is about three generations of Mexican Americans in Los Angeles.[xl] Later, he played a widowed father in the 2002-2004 PBS drama, American Family: Journey of Dreams.[xli] His character in this film is Jess Gonzalez, a widower, patriarch of his family, and veteran of the Korean War. The loss of his wife connects him to Adama’s role as divorcee and virtual widow when his ex-wife and mother of his children is killed in the Cylon sneak attack. Also, the Cylon wars in BSG are like the Korean War in that they are both considered forgotten, and it’s Adama’s charge to remind people that, “the day comes when you can’t hide from the things you’ve done anymore” (Mini-series). Unlike Greene, Olmos has a history in SF that firmly presages his involvement in the BSG re-imagining. He played the enigmatic, origami folding Los Angeles cop, Gaff, in Ridley Scott’s 1982 film, Blade Runner,[xlii] based on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?[xliii] Gaff’s role is primarily that of an emissary sent to retrieve and maintain contact with the story’s blade runner, or replicant hunter, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford). Despite his minimal screen time, it’s his character that plants the hint in the minds of Deckard and the audience that Deckard is a replicant with false, implanted memories. His character destabilizes the assumption one makes about their humanity, history, and memories. In this way, his character plays a crucial role in the philosophical problemization developed in the film. Additionally, he’s primarily the only Chicano character in the film even though it takes place in a future Los Angeles. This doubly makes him an alien within the context of his own home, which in this future-scape is inhabited by android replicants, white sergeants and blade runners, and Asian business owners and bystanders. In addition to his patriarchal and future police roles, his arguably most recognized television character prior to his involvement with BSG is as the character Lieutenant Martin Castillo on the 1984-1990 television show Miami Vice.[xliv] He commanded the rogue vice squad cops Sonny Crockett (Don Johnson) and Rico Tubbs (Philip Michael Thomas), often berating their zealous immersion and extra-police tactics while guiding them to the successful apprehension of Miami’s worst criminals. These roles point to a possible double meaning for his call-sign, “Husher.” One meaning is one that hushes or silences. This reflects the fact that he’s often an authority figure and deserving a certain respect and silence when he’s speaking. Another meaning could be the archaic “to usher.” He guides those under his command or in his family through trials and tribulations to a better place past their troubles.

Olmos’ portrayal of Adama draws on this past work, and audiences of the new BSG are more than likely aware of his filmography. That being said, he goes beyond that work in the character of Adama. Like much else in the series, he’s a hybrid character. His Adama is best labeled a seemingly mutually exclusive liberal conservative. Most of his initial reactions are firmly established in his military training as a good soldier and strategist. However, he is a worldly individual who reads books and entertains other opinions and options. The re-imagined Adama may not be as wholesome as his predecessor, but he makes his final decision on any given issue after careful consideration within or through deliberation and debate with those persons he most trusts.

Olmos has strong convictions in his personal life that compliments the kinds of characters he portrays. He is a well-known Latino activist who founded and chairs Latino Public Broadcasting. Also, he is a political activist. He spent twenty days in jail following his arrest protesting the United States Navy bombing practice on Vieques Island, Puerto Rico.

Olmos, like Greene, announces to the fleet at the end of the mini-series that he knows the way to Earth, but he does not usurp religion or assume a prophet status in the same way that Greene’s Adama does so. That role in the re-imagined series is handled by the “school teacher” turned President, Laura Roslin.

President Roslin and a Politics Infusion in the Re-Imagined Series

Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell) rises to the occasion as the new President of the Twelve Colonies of Kobol following the Cylon sneak attack. Halfway through the 2003 Mini-Series, an automated radio announcement tells all government personnel to follow “Case Orange,” which is a protocol to determine who of the government’s cabinet is still alive and who succeeds to the presidency. Roslin is forty-third in line (as Secretary of Education), and her number comes up. She’s sworn into the Presidency in a scene reminiscent of the swearing in of Lyndon B. Johnson following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, and she immediately uses her new powers to effect what she believes the best hope for humanity–a rescue operation. This is antithetical to Adama’s rush to enter the fight with the Galactica. This conflict is not the only time Adama and Roslin come to loggerheads over an issue, but it’s also certainly not the only time that they ultimately cooperate for the greater good of the fleet.

Roslin’s history as a teacher and former Secretary of Education for the Twelve Colonies, it’s possible that the producers were expanding on the original series’ Athena character. Athena was a Viper pilot turned teacher. The wholesomeness of the show necessitated a rounded family environment in the wagon train to the stars. Roslin comes from a difference vector as a teacher turned political cabinet member turned president. That, along with her being female, it’s interesting that they chose to make her character apparently rise in power and status rather than the other way around for Athena in the original series.

During her tenure as president, she’s employed illicit drugs procured by Dr. Cottle (Donnelly Rhodes), attempted to rig an election, and her first cancer remission was brought about by an infusion of human-Cylon hybrid blood provided by Athena and Helo’s child, Hera (who Roslin orchestrated to be hidden in the fleet after Cottle lied to the parents that the child had died). She has proven herself to be pragmatic and deceptive when necessary such as extracting information from the Cylon, Leoben Conoy (Callum Keith Rennie) in “Flesh and Bone” (20 September 2005) before flushing him out the airlock. She’s kind to those close to her, and she lives down betrayal very hard.

There is no clear-cut opposite of her character in the original BSG series other than the patriarchal leader and prophet, Adama. In a sense, the new Adama and Roslin are archetypal characters taken from the conflict envisioned by Eisenhower in his naming of the military-industrial complex. Adama represents the military and Roslin represents the last vestiges of a near-broken democracy. Coincidentally, this kind of power sharing or conflict is epitomized by an earlier television film that both McDonnell and Olmos appear. In 1997, McDonnell played the judge and Olmos played a juror in the remake of 12 Angry Men.[xlv] Judges and jurors are not necessarily at odds with one another, but a judge in most situations is meant to be held to the determination of the collective jury. In the 2003 BSG, this arrangement is inverted and expanded to the point where they agree to split their powers. Roslin is in charge of fleet affairs and Adama reserves all military decisions to himself. This strenuous relationship is challenged at times, particularly following the reappearance of the battlestar Pegasus with Adama’s superior officer, Rear Admiral Helena Cain (Michelle Forbes). Forbes’ character originates from the original series with Commander Cain (Lloyd Bridges) and his battlestar Pegasus. Cain’s name is probably inspired by Herman Wouk’s 1951 novel, The Caine Mutiny,[xlvi] and it’s subsequent 1954 film[xlvii] starring Humphrey Bogart as Queeg.[xlviii] This is an interesting role for Bridges who previously played as the competent Col. Floyd Graham in the early anti-nuclear SF film, Rocketship X-M (1950), [xlix] and as Mike Nelson, an ex-Navy diver turned independent scuba diver in the television series Sea Hunt (1958-1961).[l] Another conflict arose during the first democratic election of the fleet, in which Roslin’s supporters attempted to rig the election after realizing that Baltar had a good chance at winning. This tactic was eventually withdrawn, but politics, particularly when Roslin knows Baltar to be a liar, becomes very dirty and protracted–a war amongst dueling ideologies and different opinions of justice and truth.

Roslin’s character borrows a great deal from the original BSG and Greene’s Commander Adama. Instead of saying that her character is an archetype, it’s more accurate to say that the producers of the re-imagined BSG split the original Adama’s roles in the new series. Originally he was leader and prophet–virtually a Moses in space. In the re-imagined series, Roslin serves as political leader and prophet over the path to Earth. She assumes Adama’s foolhardy and deceptive promise of the mythical Earth after her own religious reawakening and visions produced by the illicit drug chamalla administered by Dr. Cottle to treat the pain resulting from cancer. These experiences coupled with dreams and her interaction with the prophet-like Cylon Leoben Conoy, results in her dedicated search for Earth by relying on the human polytheistic religion handed down by the Lords of Kobol in the “Sacred Texts.” The President’s identity becomes wedded to the search for Earth, and it’s this alignment that Baltar uses to discredit her ability to lead prior to the first election. Additionally, Adama believes in science and technology to deliver humanity’s last stand through the exodus, and any religious beliefs he may have are muted or altogether nonexistent. However, he, as is true for real-life politicians, realizes the utility of religion and he often pragmatically goes along with Roslin regarding the discovery of Earth despite the less than rational explanation for the circuitous path that humanity’s followed thus far in the series.

Top Gun in Space

Stinger–Maverick, you just did an incredibly brave thing. What you should have done was land your plane! You don’t own that plane, the taxpayers do! Son, your ego is writing checks your body can’t cash. You’ve been busted, you’ve lost your qualifications as section leader three times, put in hack twice by me, with a history of high speed passes over five air control towers – and one admiral’s daughter…And let’s not bullshit, Maverick. Your family name ain’t the best in the Navy. You need to be doing it better and cleaner than the other guy. Now what is it with you?

Maverick–Just want to serve my country and be the best fighter pilot in the Navy, sir.

Stinger–Don’t screw around with me Maverick. You’re a hell of an instinctive pilot. Maybe too good. I’d like to bust your butt but I can’t. I got another problem here. I gotta send somebody from this squadron to Miramar. I gotta do something here, I still can’t believe it. I gotta give you your dream shot! I’m gonna send you up against the best. You two characters are going to Top Gun.

Lt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell (Tom Cruise) and Stinger (James Tolkan)

Top Gun (1986)

The original and re-imagined BSG series are inhabited by a number of hotrod pilots who defend their fictional fleets from the Cylon onslaught. These soldiers of the future or our future’s past promote and continue an established narrative history about the ace pilot that is firmly established in the late Cold War film, Top Gun.[li] These soldiers have to be “instinctive” and “too good,” and they have to overcome and beat history such as a bad “family name” to ascend to their vaunted position. There is also an inevitability in their skill, which means these pilots are meant to be “top gun.”

The two BSG series approach this in different ways, but they are connected by the reliance of the “top gun” myth intertwined with the family social structure. Both create a large family structure with Command Adama inhabiting the patriarchal position, but the latter differs from the first significantly in the way family status is maintained along with flight status. There are near-visible lines that if crossed result in the dissolution of the family hierarchy in an already destabilized situation of the human diaspora following the Cylon sneak attack.

The primary cast and crew of the Galactica include Adama’s real and “adopted” children. His surviving son, Captain Apollo (Richard Hatch), like his namesake is the bearer of truth, and he’s a stickler for following the rules generally, which ultimately leads to the death of his brother, Zac (Rick Springfield) during the first episode after they learn about the impending attack and try to warn Galactica.[lii] Another obvious reference in Apollo’s name is NASA and America’s third human space flight project of the same name, which began in 1961 with then President John F. Kennedy’s charge, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the earth.”[liii] Apollo’s uprightness and pleasure derived from flying in space reflect the space program that may have in part inspired his name. Apollo’s friend and resident cigar smoking, hotshot pilot is Lieutenant Starbuck (Dirk Benedict). The roots of his name are apropos for his character–star for a star pilot and buck for a free spirited young man. However, the name is probably directly from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick by way of the Pequod’s first mate.[liv] Starbuck and the Pequod both symbolize the journey. This is epitomized by the Galactica fleet which represents the American wagon train to the stars, and reinforces, “the great urge of the American imagination to light out for the territory” (John Wayne’s America 305).[lv] Apollo and Zac’s sister, Lieutenant Athena (Maren Jensen) is a bizarre character on the show, because she fulfills the duties of a bridge officer and she’s a teacher for the fleet’s children. Not to say that this would be an impossible task, but her character serves more as a device to increase the wholesomeness of the show, and her being a schoolteacher can be seen as a mitigation between her roles as a military officer and a woman. Additionally, her role diminished until she left the show in the next to last episode. Rounding out the cast is Lieutenant Boomer, played by the African American, Herb Jefferson, Jr. In the original series, Boomer is an accomplished Viper pilot and a communications expert. He plays a more reserved character than his close friend Apollo. Larson does appear to have attempted to bring more people of color to his BSG, and Boomer is not merely a token black character, but one with unique knowledge and insight that serves the crew on more than one occasion. Rounding out the command crew of Galactica is the Executive Officer (XO), Colonel Tigh (Terry Carter). Carter, also African American, is second in command of the Galatica, and he commands it during Adama’s absence. He is more conservative than Adama, shows concern about some of his commander’s choices, and is generally more strict on the pilots under his command.

The re-imagined BSG shifts these character’s identities in several significant ways. The most obvious change is that some of the originally male characters are now female. Boomer, originally a black male, is recast as Sharon “Boomer” Valerii, an asian female played by Grace Park.[lvi] The re-imagined Boomer is a Raptor (reconnaissance and communications ship) pilot, but not communications specialist as is the original Boomer. Also, she is a sleeper Cylon, which is revealed in the Mini-Series and throughout the first season of BSG. Starbuck, originally a white male, is recast as Kara “Starbuck” Thrace, a white female played by Katee Sackhoff. She’s very much the “Maverick,” who is constantly at odds with superior officers and exudes attitude towards others of her superiority in the life or death game of dogfighting or playing cards. Also, the new Starbuck has many of the original Starbuck’s vices such as having a healthy sexual appetite, smoking cigars, gambling, and insubordination (though much more overt than in the original). Starbuck’s identity at the end of season three is in question, because of her miraculous reappearance at the end of the finale when she tells Apollo that she’s been to Earth and she will show the fleet the way. Captain Lee “Apollo” Adama is played by Jamie Bamber, who is a white English-American. As Adama’s son, this is a curious bit of casting, since Olmos is clearly of Mexican origin. Nevertheless, his character often stands up for justice in an objective sense and he represents the memory of the deceased Adama patriarch and legal scholar, Joseph Adama. In fact, it’s Apollo’s impassioned speech during the season three finale, “Crossroads, Part II,” that leads to Baltar’s not guilty verdict by the tribunal. Apollo’s estrangement from his father is a continual element of the series narrative, but it is tangentially that they often connect such as in the trial of Baltar with Apollo working on Baltar’s defense and Commander Adama sitting on the tribunal.

Another major difference between the two series is racial diversity. The original was primarily inhabited by white faces with a few token characters of other races thrown in such as at the peace conference in “Saga of a Star World” or the two black characters, Boomer and Tigh, as regulars on Galactica. The re-imagined BSG has elevated Latino characters through the casting of Olmos as a starring character and his son as a recurring Viper pilot. The only regularly recurring black character is Lieutenant Anastasia “Dee” Dualla played by Canadian actress Kandyse McClure. During the course of the series, both of her long term relationships have been with white men, which is progressive, but also revealing, because of the preponderance of white faces. Her last name, Dualla, implies a duality, which might point to this element of her character’s relationships. Boomer is the only recurring Asian character, and she also has an interracial relationship with the white Chief Galen Tyrol (Aaron Douglas). This relationship ends following her being found out to be a Cylon, but a Number Eight copy falls in love and has a child with the white Karl “Helo” Agathon (Tahmoh Penikett). There is a black human-like Cylon copy known only as Simon. He pretended to be a Caprican doctor beginning with the season two episode, “The Farm.” His character has only shown up in a handful of subsequent episodes. This kind of lack of color in the new series is troublesome in that if these are the only survivors of a human exodus, what happens to the racial diversity originally found in the colonies? Does this imply that the primary survivors are predominantly white, which reflects a certain privileged position, because they had the means of spaceflight and are therefore more wealthy than those without. The producers may be making a commentary on this very subject through this kind of casting, but it could have more innocuous origins such as the fact that the series is produced in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. In 2001, the Canadian census revealed that British Columbia has an only 0.66% black population (“Visible Minority Groups”).[lvii] This contrasts sharply with the 6.7% black population of California, home to Hollywood, and 12.8% of the entire United States (“California Quick Facts”).[lviii] This analysis relies on it being a production of the United States, where the promotion of racial equality in different media is a sought after ideal. For other places such as Canada and the United Kingdom, where BSG has a strong viewer base, the lack of racial others as real subjects in the series may be less of an issue.

Baltar: Savior or Satanist/Human or Cylon?

But it is not enough to remark that contemporary attitudes–as reflected in science fiction films–remain ambivalent, that the scientist is treated as both satanist and savior. The proportions have changed, because of the new context in which the old admiration and fear of the scientist are located. For his sphere of influence is no longer local, himself or his immediate community. It is planetary, cosmic.[lix]

Susan Sontag, “The Imagination of Disaster”

Baltar in the earlier BSG series is not necessarily a scientist, but he is a well educated person of political importance and he’s aligned with technology through his hidden deal with the robot Cylon race. His character is reinvented in the 2003 BSG series in which he is a “cult figure,” eminent scientist, and politically connected mover and shaker. In many ways, these two characters are “both satantist and savior,” and their “sphere of influence” is “planetary” and “cosmic” rather than terrestrial.

The pilot episode of BSG, “Saga of a Star World” first aired on ABC on 17 September 1978. It begins with the representatives of the Quorum of Twelve aboard the battlestar Atlantia and President Adar (Lew Ayres) toasts the supposed imminent peace with the machine Cylon race following an extended war. However, Count Baltar (John Colicos), representative of Picon, conspires with the Cylons to initiate a sneak attack on the gathered fleet of battlestars and the colonies they would normally be defending in return for tyrannical control of Picon for himself. The Cylon’s desire to win by any means necessary including initiating peace talks under false pretenses in on the one hand an underhanded tactic, but it also recalls Hitler’s worthless non-aggression pacts from World War II. Therefore, the viewer is presented with images from the beginning of the Cylons as treacherous and evil in their diplomatic practices as well as their invasion and near-annihilation of humanity.

Coincidentally, the three hour long pilot was interrupted by the network to show the signing of the Camp David Peace Accords between Egyptian President Anwar Al Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at the White House and witnessed by United States President Jimmy Carter thus resolving many years of animosity and bloodshed between the two countries. Unlike the subject matter of the interrupted television show, the Camp David Peace Accords brought about positive results and were not part of a conspiratorial sneak attack.

Despite the work of President Carter, the Cold War was still as much a reality after as it was before and during his four-year term. This is reflected in the way the Cylon threat is constructed in the first (movie length) episode of the 1978 series. The sneak attack as an emblematic representation of the treacherous and insidious enemy was firmly established in the American consciousness following the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, particularly after President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for a joint session of Congress on December 8 and he proclaimed the now famous words, “yesterday, December 7th, 1941 – a date which will live in infamy – the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan” (Roosevelt par. 1).[lx] He went on to define how the attack was planned well in advance and there was no warning on the part of the Japanese even though the United States had been in talks with their ambassadors. The Japanese sneak attack shocked the nation and was quickly appropriated by culture producers in Hollywood. Additionally, the event strengthened the national self-image of honesty and trust in opposition to a distrustful enemy-other.

Lord Baltar fills the role of the Japanese delegates, which FDR mentions in his short but passionate speech following the Pearl Harbor attacks. He assumes one face for humanity, while making covert deals with the Cylons behind the scenes for his own aggrandizement. There’s a great deal of significance to Baltar’s name in both the 1978 series and the 2003 re-imagined series that relates to his duplicitous role. Lord Baltar’s name may originate from Bhaltair, the Scotish form of the Germanic name Walter, which means “ruler of the army,” and derives from the words: wald or ruler and heri or army. Lord Baltar aspires to rule the colony Picon as its supreme dictator. However, after the human survivors’ escape and exodus, he is drafted by the succeeding Cylon Imperious Leader to command a basestar in pursuit of the survivors. The Cylons believe his being human will provide insight into the motivations and designs of the more wholesome survivors fleeing the Cylon threat. To this end, Baltar is assigned the IL model Cylon, Lucifer as second in command as well as objective third-person (or third-machine) observer. This Cylon scrutiny results in a new double meaning for Lord Baltar. On the one hand, his name is made a pun of balter, or to tumble about or dance clumsily. He performs for his Cylon masters who hold his life in the balance. His running the Cylon created maze most importantly illuminates the anagram of Baltar’s name: lab rat.

Whereas Lord Baltar played a deceptive role akin to the Japanese ambassadors to the United States in talks with FDR’s government prior to the Pearl Harbor sneak attacks, the re-imagined Dr. Gaius Baltar (James Callis) inadvertently reigns destruction on humanity through his careless arrogance and egomania by literally sleeping with the enemy, the Number Six Cylon (Tricia Helfer). The new Baltar is introduced in the Mini-Series by the camera focused on the dual pane television in Baltar’s home on Caprica. It’s displaying a live interview of the imminent celebrity scientist as Number Six, later called Caprica Six, walks in and smiles, seemingly proud of her lover. The “Spot Light” interviewer describes Dr. Gaius Baltar as, “winner of three Magnet Awards over the course of his career, media cult figure, and a personal friend of President Adar. He’s currently working as a top consultant for the Ministry of Defense on computer issues, but he’s perhaps best known for his controversial views on advancing computer technology” (Mini-Series). He’s well connected and he provides his special access to the Ministry of Defense to Number Six, in return for her favor and assistance on his own projects. He doesn’t know that she’s anything more than an unnamed defense contractor until just before the Cylon bombs rain down from the skies. However, his irresponsible and unguarded control of his own access to the Defense mainframe is not what really makes the new Baltar the proverbial bad guy. It’s his immediate concern of self, self-preservation, and cover-up of his wrongs that mark him as a betrayer lacking any solidarity with his fellow survivors fleeing the Cylon threat.

The 2003 re-imagined series introduced a very different Baltar. Instead of a political leader, the new character is a computer scientist and heralded as a genius. Dr. Gaius Baltar earns his credentials as well as a prename, unlike his predecessor. His first name, Gaius is a common Roman praenomen or given name that is arguably famous by its attribution to the Roman emperor, Gaius Julius Caesar (12 July 100 BC-15 March 44 BC). The Roman meaning of Gaius or Caius is lost, but its connection to the Caesar line implies ruler or perhaps megalomaniac. The new Baltar is most certainly a self-interested, arrogant, and opportunist character and its his lack of thinking beyond his own ego that resulted in the Twelve Colonies being compromised and slaughtered during the Cylon sneak attack. Unlike the explicit cooperation of the original Baltar with the Cylons, the new Baltar’s personal flaws and egocentrism are what elevate him to the duplicitous and sinister role of his original’s namesake. Furthermore, his actions and conspiring elevate him over the “pantomime villain” of Larson’s original series (McGrath 16). Also, it’s fascinating how the new Baltar’s character changes over time. We are first introduced to him as a scientist and celebrity worthy of television interviews regarding the constraints placed on researching artificial intelligence. Later, hiding his involvement in the attacks, he works with President Roslin and Commander Adama to develop a Cylon detector that he subsequently sabotages. Then, he comes full circle with his predecessor and establishes himself as a politician–first winning the presidency from Roslin and inadvertently opening the way for the later Cylon occupation on New Caprica and then, his incarceration as a traitor, which he spins as being a political prisoner propounding Marxist ideology. As Susan Sontag points out about earlier SF films, the scientist may be a “satanist or savior,” but in newer SF, as evidenced by the new BSG, scientists become political figures which shifts the threat from science and technology to politics and ideology (Sontag 218). However, Baltar’s influence is always greatest in space aboard Galactica or a Cylon basestar in stark contrast with his failed presidency on the surface of New Caprica. The re-imagined Baltar’s influence is only potent when it’s disconnected from a localized planetary body making his influence truely “planetary, cosmic” (Sontag 218).

Number Six – Cylon, Human, or Construct?

Are you alive? […] Prove it.

Number Six (Tricia Helfer) in BSG Mini-Series